Armenity, the Republic of Armenia's pavilion for the 56th Venice Biennale, is set on the island of San Lazzaro degli Armeni. As the headquarters of the 300-year-old Armenian Mekhitarist Order, the monastery has played a critical role in Armenian history and the preservation of Armenian culture abroad. This significance makes the monastic island an ideal crucible for the 100-year commemoration of the Armenian Genocide.

Curated by Adelina Cüberyan von Fürstenberg, 16 artists were drawn from the Armenian diaspora to integrate—and at times intervene—in the landscape and architecture of the Island. In the monastery’s gardens, Mikayel Ohanjanyan’s sculpture of deconstructed streetlights and Mekhitar Garabedian’s sound installation are memorials to the forgotten: family, friends and fellow citizens. Inside, Sarkis Zabunyan, better known as Sarkis, extends his series of stain-glass images from the Turkish pavilion to Armenity. Installed in an actual place of worship, the works take on a profound meaning that gives a sense of resolution to his installation at the Arsenale.

Within the monastery’s vast collection of religious icons, historic objects, literary texts, paintings, and antiques, the exhibition inserts complementary narratives. Among a display of traditional printing presses (the island was also an important publishing centre for over 100 years), Nigol Bezjian's installation is inspired by the life and death of the Armenian poet Daniel Varoujan. The artist reproduced images from Aztag Daily, which was one of the 600 or so Armenian publications operating in Turkey until 1915. Bezjian’s installation reflects on the relationship between language and memory, as well as the notion of bearing witness.

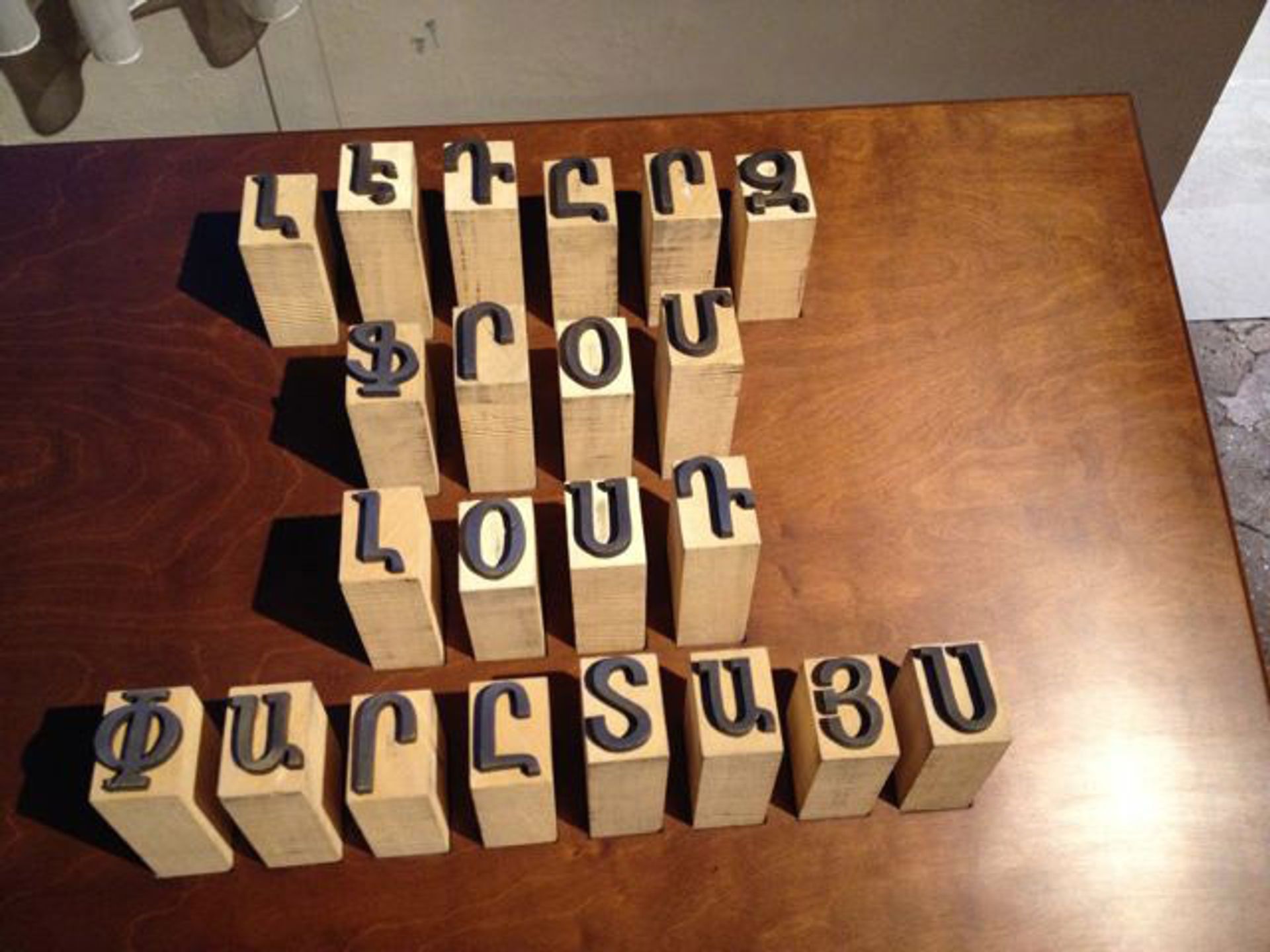

Testimony and translation are recurring themes in the exhibition. The artists—all of whom are grandchildren of survivors of the genocide—attempt to find alternative strategies for depicting personal and collective history. In the library, Hera Büyüktaşçıyan connects Lord Byron's history on the island of San Lazzaro, where he learned the Armenian language, to the struggles of Armenians in Anatolia with the Turkish language. Her kinetic sculpture plays with the historic use of Armenian letters to form Ottoman Turkish words. It reads “Letters from Lost Paradise” in reference to Byron's claim that Armenian was “the language of Lost Paradise”.

Silvina Der Meguerditchian uses her great-grandmother’s folk recipes (also written in Turkish with Armenian script) as a departure point for a display of objects, materials and ingredients for the different medical remedies. Nearby, Yervant Gianikian and Angela Ricci Lucchi illustrate ancient Armenian fairytales recounted by Gianikian’s father (who is also the subject of their video Ritorno a Khodorciur in which he reads extracts from a diary that documents his emotional departure from his native country). Intergenerational exchange is also at the heart of Nina Katchadourian’s video series. With a vocal coach, the artist attempts to learn her parents’ different accents, while they attempt to speak with her American accent. It is a comical but moving commentary on displacement and assimilation. Meanwhile, Hrair Sarkissian reminds us of ongoing struggles by some Armenian communities to reconcile with their past. His dark photographs document descendants of Armenians in Turkey who, having converted back to Christianity from Islam, feel forced to suppress their identities.

While the exhibition carefully frames different arguments about the role of art in responding to such horrific acts of violence, murder and forced migration, it also demonstrates the function of art to reimagine these arguments. Around the cloisters, Rosana Palazyan draws parallels between images and terminology used to describe weeds and other invasive plants to those used to dehumanise and stereotype marginalised communities. Haig Aivazian transforms the traditional oud into an elegant, but useless sculpture that conceptually depicts migration patterns. Through archival images, Aikaterini Gegisian’s collages attempt to remap different transnational relationships and political narratives.

Ayreen Anastas and Rene Gabri directly confront their responsibility as artists and the uncomfortable questions that arise from Armenity. In addition to a well-conceived installation of archival images and materials from the monastery, which the artists annotated, they are leading a discussion around the grounds of the monastery. The walk unpacks the issues encountered during their research and provides a context to address—as the artists explain in the exhibition notes—“the necessity of art as affirmation of life and as resistance—as resistance against death, as resistance to genocide, as resistance to the thanatopolitics or necropolitics which haunts and marks our time.”