New Objectivity: Modern German Art in the Weimar Republic 1919 to 1933, Museo Correr It is sheer coincidence that the Museo Correr’s exhibition on New Objectivity fits so elegantly with the themes of Okwui Enwezor’s anti-capitalist Biennale, says Stephanie Barron, its curator. The artists associated with the movement worked through and responded to the 14 years of Weimar Germany (1919-33), when the country veered between devastating unemployment—fuelled by hyperinflation and crippling reparations—and the decadence of the Golden Twenties.

New Objectivity: Modern German Art in the Weimar Republic, 1919-33, which will travel to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art in September, includes more than 140 works by 42 artists (this list will swell when the show heads Stateside). Earlier shows on the topic have largely dealt with “the sexy aspect” of New Objectivity, Barron says, referring to the most celebrated facet of the movement: portraits by key figures such as Otto Dix, George Grosz, Max Beckmann and Christian Schad. Such portraits, including Otto Dix’s Portrait of the Lawyer Hugo Simons (1925) and Beckmann’s Portrait of a Turk (1926) still get pride of place in the show, but it is the addition of photographs, still-lifes and hitherto more marginalised artists that gives the movement a freshness here.

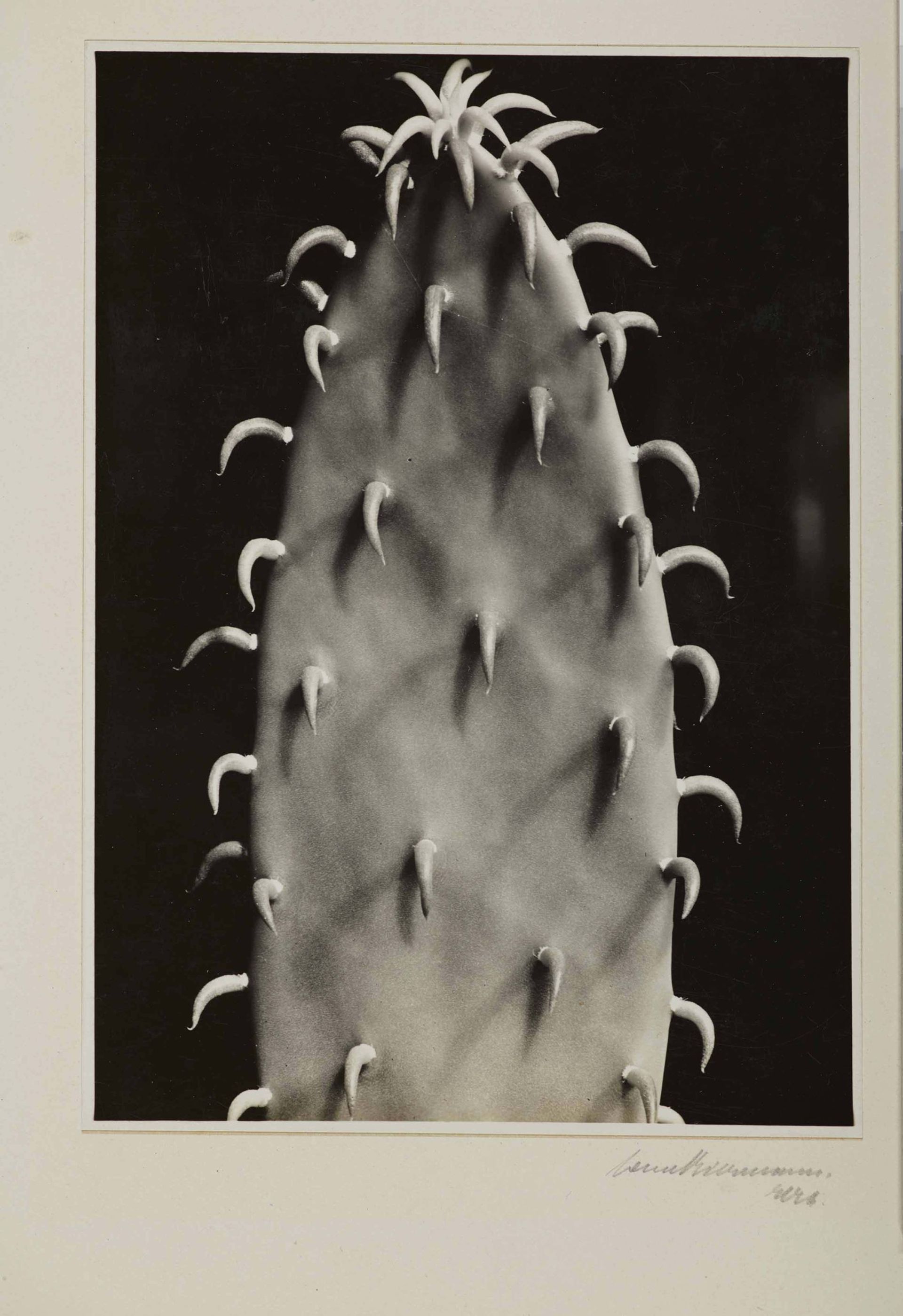

As consumerism and industrialisation took hold in Weimar Germany, artists began to shift their focus away from people towards inanimate objects. Photographers such as Hans Fischer were hired by companies to promote their products, elevating everyday items such as dishcloths and light bulbs to legitimate subjects. The relationship between these photographs and the painted masterpieces provide some of the most surprising new insights on this defining movement of 20th century German art. Julia Michalska

Frontiers Reimagined, Palazzo Grimani, 9 May-22 November Frontiers Reimagined, an official Biennale collateral event at the Palazzo Grimani, aims to "demonstrate the intellectual and aesthetic richness that can emerge in today's globalised art world when artists engage in intercultural dialogue", the organisers say. Forty four artists from more than 25 countries have been sel ected by the New York and Hong Kong based dealer Sundaram Tagore who is the exhibition commissioner (his Tagore Foundation International is behind the non-selling show).

Highlights include a work by the Brazilian artist Vik Muniz who has made a compelling diptych of chromogenic prints depicting Apollo and the Cumaean Sibyl (2007). These mythical figures were made from landfill trash and are photographed from the air. Every Breaking Wave (2014), a finely wrought, elegiac work in fine pen and oil, by the Iranian artist Golnaz Fathi stands out. A local artist Vittorio Matino enlivens the space with Beyond Blu Two 2012. "The brilliant use of colour employed by Matino is informed by his investigations into light and colour while living in the Veneto region," Tagore says.

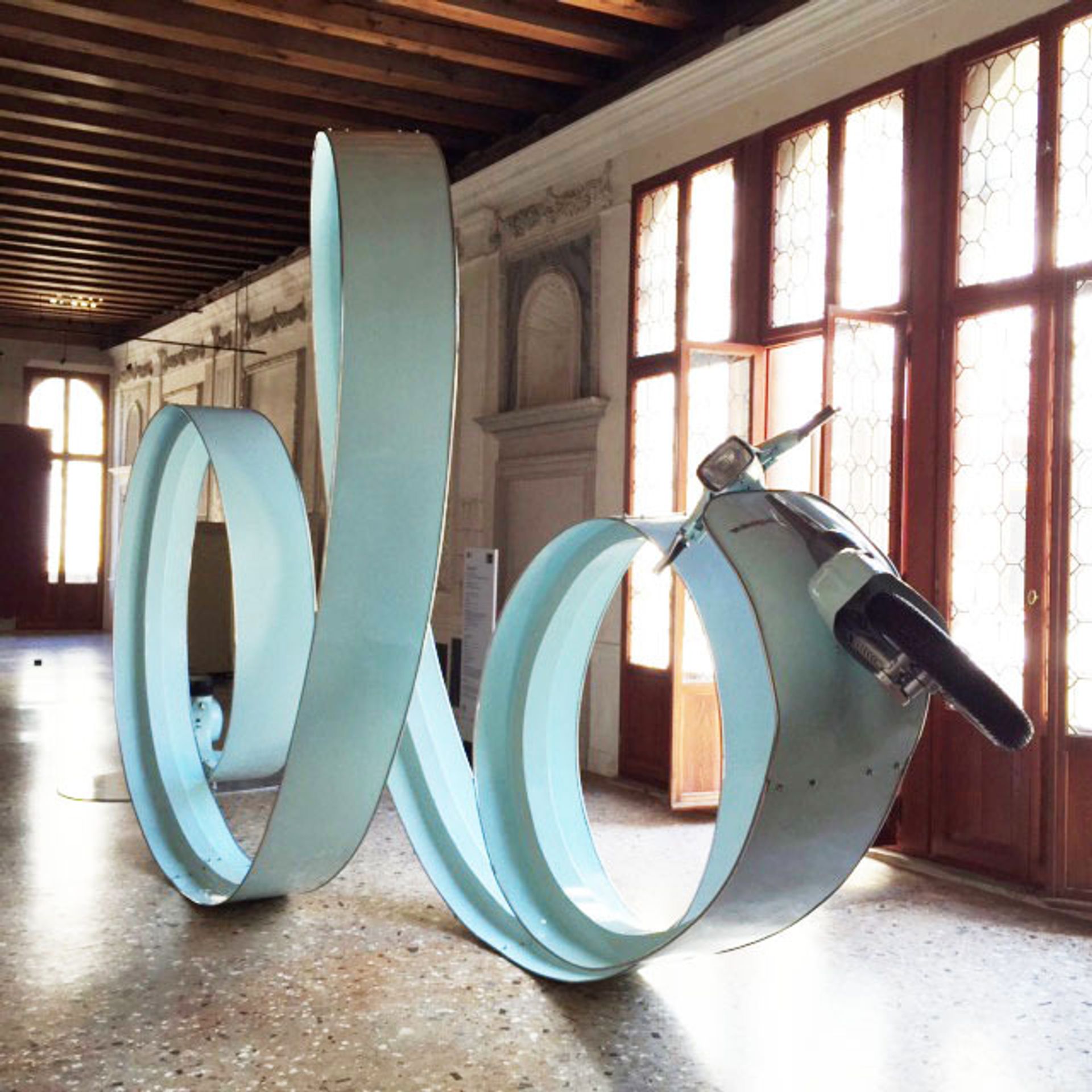

There is an element of spectacle with some works, especially Japanese artist Hiroshi Senju's Ryujin series of waterfall images (2014) created by pouring translucent paint onto mulberry paper mounted on board. These images turn electric blue under ultraviolet light (hence the gasps from some visitors). A twisting, bending Vespa is also a rare sight, bringing an element of mirth to the weighty Biennale circuit (Eddi Prabandono, After Party/Living the High Life, 2013). Gareth Harris

Proportio, Museo Fortuny, 9 May - 22 November

The Axel and May Vervoordt Foundation has assembled a long list of big names from the foundation’s extensive collection (with help from the Fondazione Musei Civici di Venezia and a host of other lenders) in a wunderkammer-like exhibition that is both eclectic and visually arresting, and put together by Axel Vervoordt and Daniela Ferretti, the director of Palazzo Fortuny.

The exhibition is centred around art that somehow speaks to or embodies the values of sacred geometry. From a curatorial point of view, the concept is arcane enough to allow for a vast array of works, installations and sculptures, which might not be related to each other from an art historical point of view, to be displayed together because they are, quite simply put, beautiful. After all, weren’t sacred proportions, such as the golden spiral, employed by the ancients to create things of beauty?

Cue works by Heinz Mack, Anselm Kiefer, Ellsworth Kelly, Kazuo Shiraga, Mario and Marisa Merz and Marina Abramovic, but also Egyptian artefacts, Dutch Old Master paintings, a large plaster model by Antonio Canova and a portrait by Sandro Botticelli. “We didn’t want politics in this show,” Axel Vervoordt says, “instead we wanted to look at timelessness, and how ideas of harmony and proportion can connect old and new art.”

The building, which houses the collection of its eccentric and wildly creative former owner, the designer Mariano Fortuny, lends itself perfectly to this show, to the point that it is often hard to distinguish the Vervoordt works from the permanent décor, which is no bad thing at all. Ermanno Rivetti

Sean Scully, Land Sea, Palazzo Falier

It takes some time to come around to Sean Scully’s work. Most of his paintings are not beautiful in an obvious way. In Land Sea, Scully's show of recent painting at the Palazzo Falier, many of the pieces are familiar in style. But the most interesting one, Slope (2015), pushes against expectations. It is difficult to like this painting, although neither its colours (pink, red, green, various shades of blue) nor its sloping slabs are unprecedented in Scully's work. But there is something disagreeable about it: it lacks the conventional prettiness that characterises so much contemporary painting.

This is all to Scully's credit. Few abstract painters consistently expand our taste, and this is especially true today. It is easy to develop a style and churn out pictures. But Scully is unhappy with too much stability. He does not want to be predictable. In that sense, Slope is a characteristic painting: it forces us to reconfigure what we think we know. This is what makes Scully the greatest abstract painter of his generation: that he is unafraid to be ugly today so that he may be beautiful tomorrow. Pac Pobric

Ursula von Rydingsvard, Giardino Della Marinaressa

Sculpture, more than any other form, relies heavily on its context; it is the least autonomous art. Few sculptors account for this problem well enough to merit continued interest, and Ursula von Rydingsvard is not that rare artist whose sculptures look great inside. But her show of six works in the Giardino Della Marinaressa, a small, beautiful park just outside the Giardini of the Venice Biennale, is a treasure.

Her pieces stand like totems, although there is no reason to believe that they represent anything but themselves. Several of the works are made in cedar or bronze, but the most interesting piece is the least naturalistic one: Elegantka II (2013-14) is made of polyurethane resin and stands out sharply among the trees behind it. However, there is little conflict between this sculpture and the park. As a frame, the perfectly manicured Giardino Della Marinaressa brings out the greatest potential beauty from von Rydingsvard's works. In another setting, these works would likely not look as good. Pac Pobric