All the World’s Futures, the central show at this year’s Venice Biennale, which is organised by Okwui Enwezor, focuses on capitalism and history, but there is more to it than that. In our round-up of the most important themes to look out for, our team focused on a number of recurring motifs: violence, labour, artists from diasporas, spectacle and a didactic curatorial approach.

Yet even these themes can be restrictive. The Arsenale, which hosts the second part of the main show, has a majority of the works on view, and the art often outruns the show’s strict ideas. It is difficult to box everything into an inflexible concept. Instead, this round-up of the Arsenale puts individual works and artists first.

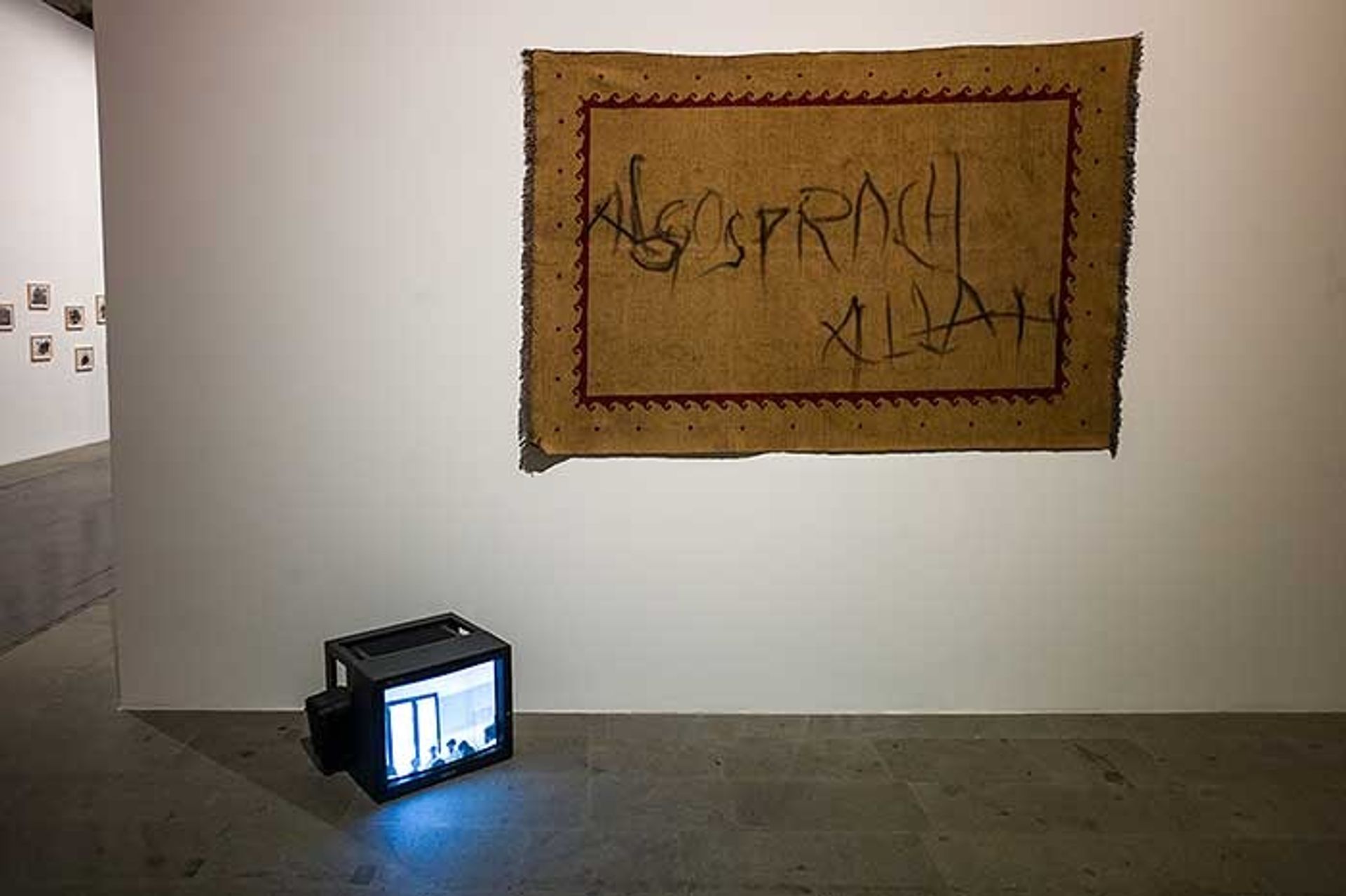

Adel Abdessemed, Also Sprach Allah (2008) The Algeria-born artist Adel Abdessemed does not shy away from tackling 21st-century taboos. The catalogue entry for All the World's Futures describes the artist's vision as uncompromising, adding that "Abdessemed's work always appears to be in a state of high alert."

Visitors entering the Arsenale see a crude carpet emblazoned in clumsy, illegible daubs that read “Also Sprach Allah,” which translates as “Thus Spoke Allah”. An accompanying video documents how this work was made: it shows Abdessemed cradled in a blanket, being tossed into the air by a group of men. With each throw, he adds a mark to the carpet, which is pinned to the ceiling (the impressions eventually spell out the eponymous title).

Also Sprach Allah was first shown at the David Zwirner gallery in New York in 2009. The gallery said at the time that the work demonstrates "how a group can propel an individual to take action in the name of God.” The work also alludes to the novel Thus Spoke Zarathustra by the German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche, which examines the idea of the death of God (Nietzsche dissects the concept that divinity governs human life). Abdessemed's piece is subsequently as potent as his previous work—hardly surprising given that the artist once told The Art Newspaper that "politics can be as vicious as a chimpanzee.”

Melvin Edwards, Ida W.B. (1990) Like many of the artists in All the World's Futures, the African-American sculptor Melvin Edwards addresses issues of race, labour rights, coercion, constraint and the experience of diaspora communities.

In the Arsenale, Enwezor has placed a series of Edwards’s iron wall sculptures in a facing rank, between whose accusing lines visitors must walk. Edwards is a highly accomplished welder (and has taught in the US and Africa) and his folded, contorted axes, chains, manacles and hammerheads are imbued with a sense of unspeakable, shameful horror and an unhealthy, luxuriant invitation to caress and desire. The works simultaneously reference African masks and Futurist weapons of war, so that there is a sophisticated commentary on the aesthetics of violence and the experience of slavery and domination.

The theme is repeated in other works in the show including Monica Bonvicini's Latent Combustion (2015), Pino Pascali's Cannone Semovente (1965) and Adel Abdessemed's Nymphéas (2015)—though these pieces have less of the implied explosive energy that enriches Edwards’s deceptively modest work.

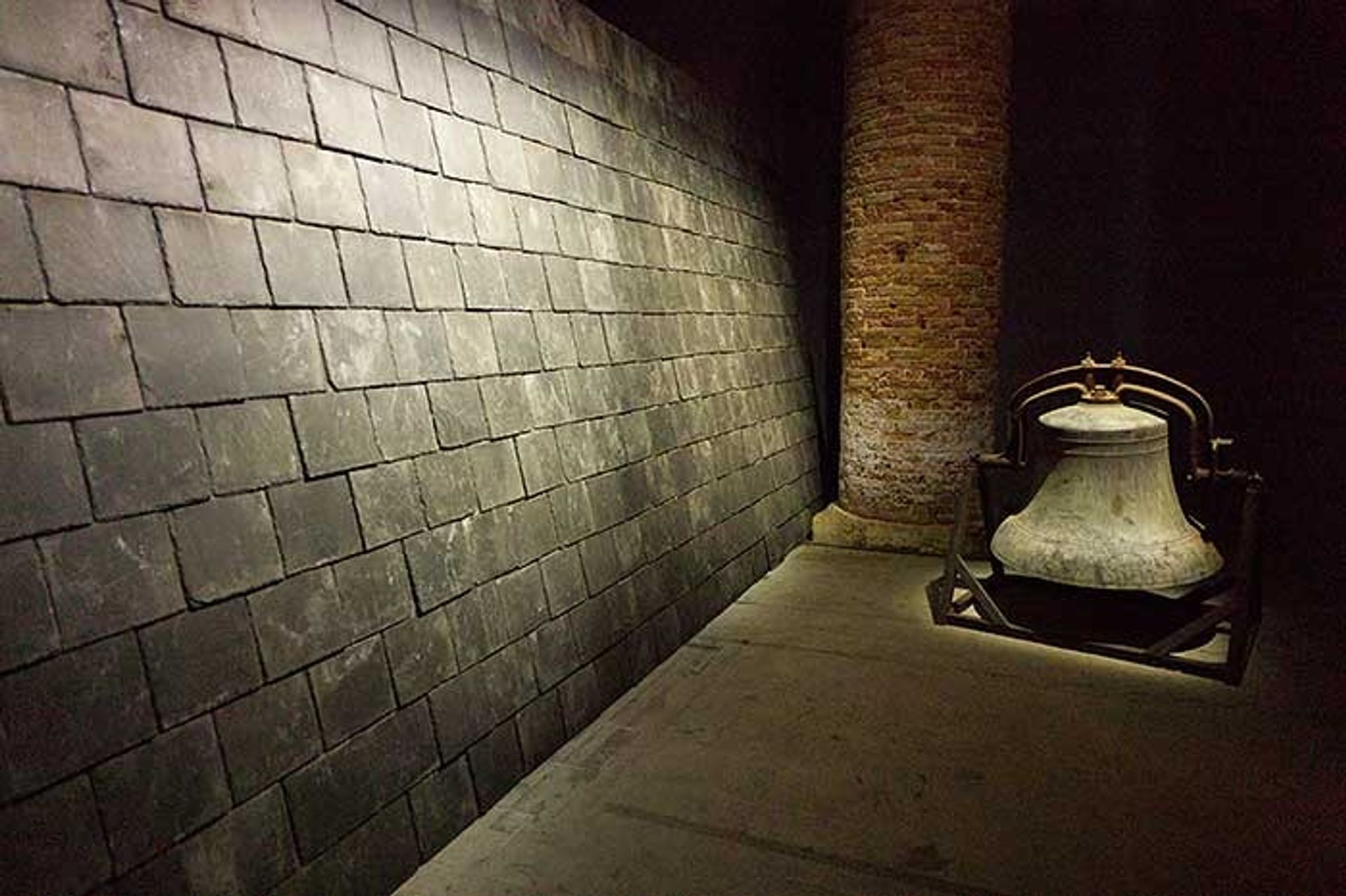

Theaster Gates, Gone Are the Days of Shelter and Martyr (2014) Theaster Gates is arguably one of Chicago’s most famous activists—and certainly now its most famous contemporary artist. His installation in the Arsenale section is one of the strongest works on view.

A bronze church bell, a wall of slate roof tiles, a mostly-complete statue of a saint: these are the items that Gates and his team have salvaged from the now-demolished Roman Catholic Church of St. Laurence in Chicago, which was built in 1911. The Joseph Molitor-designed church, which gradually fell into disuse, was on the border of changing ethnic and denominational communities. Gates uses the semi-demolished church interior to screen an affecting, atmospheric video filmed with his collaborators, the Black Monks of Mississippi: two powerful performers raise and drop heavy church pews to an irregular beat while a cello plays softly and, in the background, a blues-gospel chant creates a lyrical, elegiac mood.

Gates is known as much for his social activism as for his art. His sculptures, paintings and installations fund, and frequently refer to, his ongoing project to renovate decaying buildings and to create art and education projects that empower communities. The idea of re-imagining a better (or different) world through the built environment echoes throughout Enwezor's show: from Isa Genzken's models in the Palazzo delle Esposizione to Ala Younis's Plan for a Greater Baghdad (2015) to Cao Fei's Le Town (2014).

Katharina Grosse, Untitled Trumpet (2015) After the subdued, largely black-and-white colour scheme of Enwezor’s show in the Giardini, Katharina Grosse’s psychedelic, Technicolour installation in the Arsenale comes as a bit of a shock. Untitled Trumpet (2015), which fills an enormous gallery, looks like a spray-painted alien planet: fabric painted in purple, yellow, green and red is draped over the walls and gravel covers the ground, painted in the same colours. It is unclear whether you have just stepped into a bright abstract painting or some version of Mars imagined in the 1970s.

This is not the only luminous work in the show. Enwezor begins the Arsenale installation with early multi-coloured neon works by Bruce Nauman, while Chris Ofili’s fluidly colourful paintings fill an entire gallery. Tiffany Chung’s appealing pastel hues momentarily detract from the serious subject matter of her work: the humanitarian crisis in Syria. Violence and death do not always come in black and white.

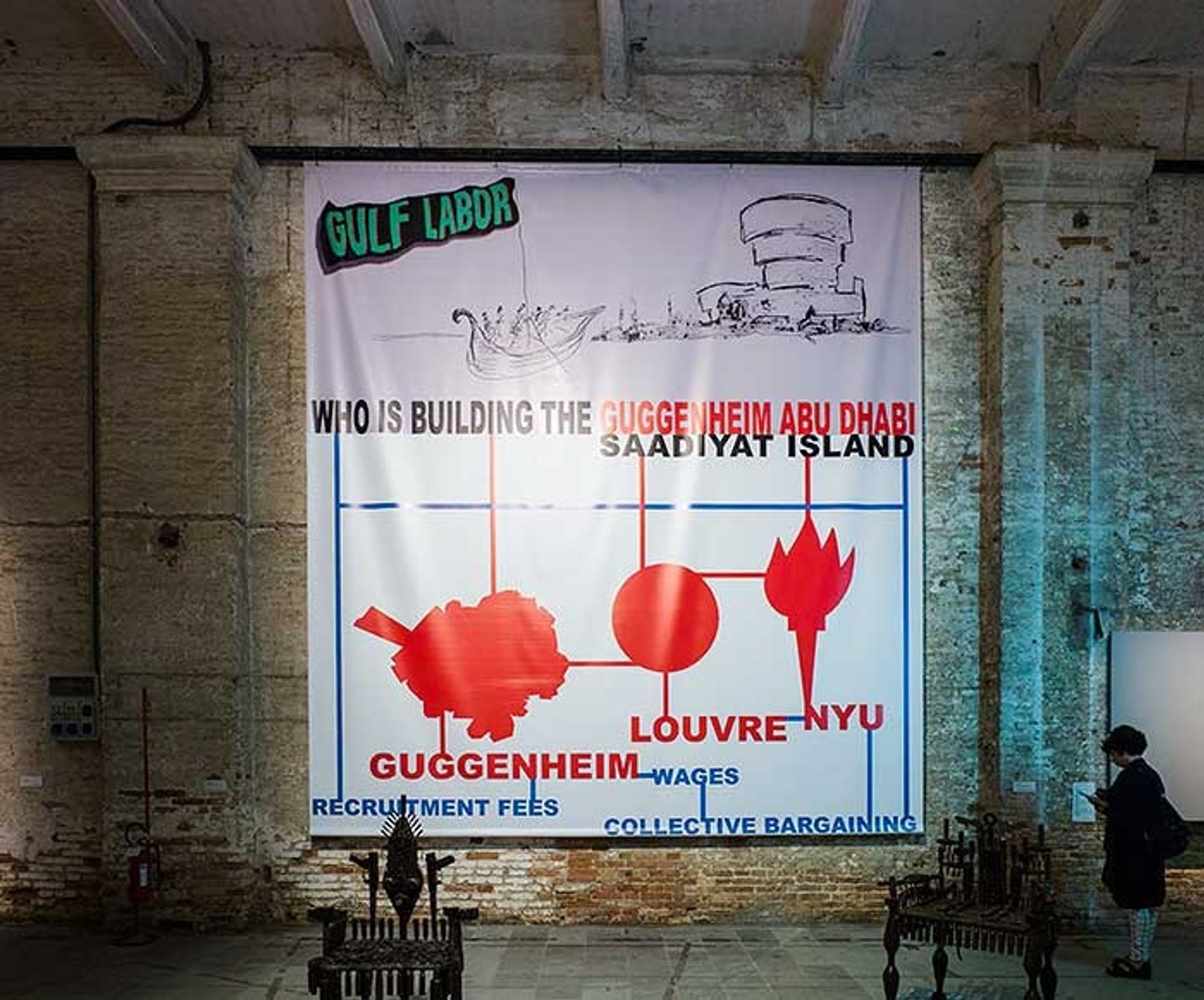

Gulf Labor, Who is building the Guggenheim Abu Dhabi (2015) Many works in Enwezor’s exhibition touch on broad themes such as capitalism, colonialism and inequality. But Gulf Labor’s Who is building the Guggenheim Abu Dhabi (2015) looks at those issues in a way that hits home for the art world. Since 2010, this international group of artists has been raising awareness of the plight of migrant workers building cultural centres in Abu Dhabi. This work in the Arsenale, a large poster, paints a simple picture: the Guggenheim, the Louvre and New York University are developing projects in the oil-rich emirate that neglect worker welfare. This is the second Venice outing for Gulf Labor so far: its campaign is also included in Hans Haacke’s, World Poll (2015), a 20-question iPad survey in the Giardini. But here, Enwezor has possibly provided the group with its most visible soapbox.

Steve McQueen, Ashes (2014-15) Photography and film are always about death: by the time we see a picture or a movie, the moments are already gone. It has been 13 years since the British filmmaker Steve McQueen travelled to Grenada, where he met a young man, Ashes, who is at the centre of the short and beautiful documentary film Ashes (2014-15, though the work was filmed in 2002). We see the chiselled young man, who never speaks, aboard a small ship that chops through the sea off the coast of Grenada. Everything about the piece is beautiful: the setting, the cinematography and even the graceful, handsome main actor.

Those moments aboard the ship are long gone and so is Ashes. During a brief voiceover, we learn from Ashes’s friends that he was killed after the film was made: “he tried to run and they shoot him in the back and when he fell, one of them guys went over to him and shot him up around his belly and his legs and thing.”

It is a painful end to a pleasant film, and its horror cuts against how quiet it otherwise is. In McQueen’s work, violence is often explicit: his 2011 film Shame, about the 1981 Irish hunger strike, includes scenes of beautiful brutality. Ashes is a softer film—but it is no less frightening.

Gedi Sibony, A Month of Saturday (2015) There is a lot of painting at the Arsenale, and among the artists given considerable space are Chris Ofili and Georg Baselitz. Each is given his own gallery, but it is the US artist Gedi Sibony’s simple pictures, spread throughout a section of the Arsenale, that steal the show.

Sibony’s works are all on the surface, but that is not a slight: painting is necessarily only about what is immediately visible. It is impossible to dig deeper than what his paintings present us with. A picture like A Month of Saturday (2015) is beautiful in the simplest way. Atop a re-purposed aluminium sheet (it used to be part of a trailer) is a swath of white paint. Below that is a picture of some clouds and grass. Does any of this relate to the title? It is impossible to say, and perhaps only Sibony knows for sure. What we see is beyond interpretation, but we do not need to make sense of good painting. All we need to do is look at it. Sibony’s work, especially because it is casual and easy, is a moment of respite in an otherwise busy and sometimes intellectually overwrought exhibition.