At first glance, Salvatore Settis and Miuccia Prada may not appear to be an obvious pairing. One is a world renowned archaeologist, Classical art historian and the former director of the Getty Research Institute in Los Angeles and the Scuola Normale Superiore of Pisa; the other, the fashion designer and entrepreneur behind an international luxury powerhouse. This is where the Classical meets the contemporary and two apparently distinct worlds collide.

On 9 May, the Prada Foundation, established in 1993 to promote contemporary art as well as architecture and cinema projects, is due to open a new venue in Milan with an exhibition of ancient art that unexpectedly diverges from its mission. For the occasion, Prada brought Settis on board to organise not only the inaugural Milan show but also its twin, installed in parallel at the 18th-century Palazzo Ca’ Corner della Regina, the home of the Prada Foundation in Venice.

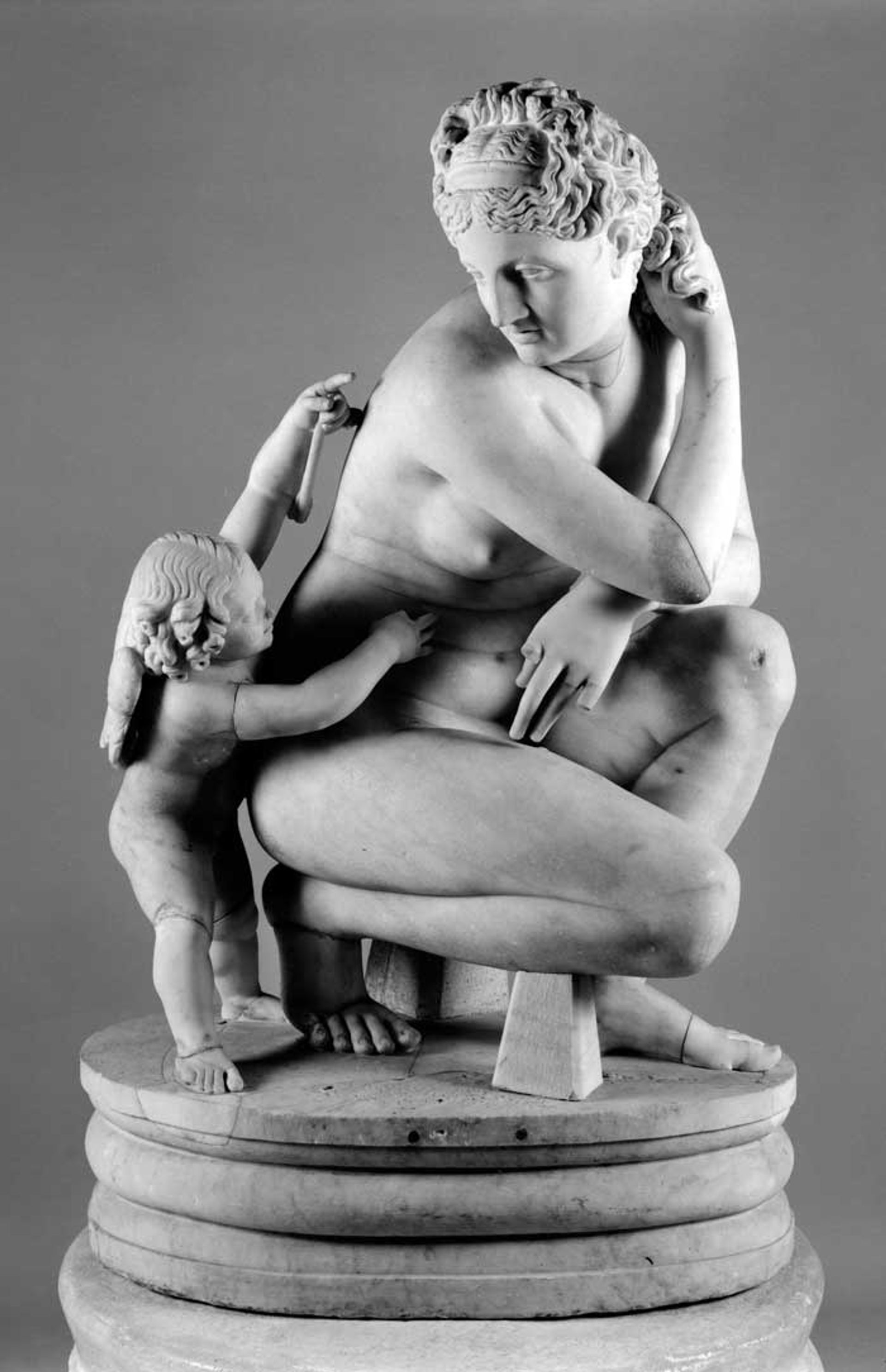

In Milan, the exhibition Serial Classic: Multiplying Art in Greece and Rome develops the theme of seriality in Classical art, while in Venice, Portable Classic: Ancient Greece to Modern Europe focuses on small-scale reproductions of Greco-Roman sculpture from the Renaissance to Neo-Classicism. While the show in Milan examines the relationship between originals and copies in Greco-Roman sculpture in terms of the methods and materials used, its Venetian counterpart considers the ways in which miniature reproductions of great masterpieces such as the Farnese Hercules and the Apollo Belvedere were collected and created.

How do you think the public will react to the Prada’s inaugural exhibition in Milan?

That I can’t say. But there are three aspects which intrigued me and could be attractive to the viewer. On the one hand there is the Prada Foundation, itself connected to the very famous fashion brand, to trends and to the cultural profile of the padrona di casa [Miuccia Prada]. The second aspect is Rem Koolhaas, one of the most talked about and cultivated architects, who has designed not only the spaces of the building but also the installation of the two exhibitions. The third element is the project to show Classical art from an unusual perspective. The combination of these three aspects in an exhibition of Greco-Roman art is unprecedented.

Where did the idea for the double shows come from?

Miuccia Prada proposed the Milan exhibition to me first, then Venice came later. She was the one who thought of an exhibition with a strong implicit cultural idea, which is that ancient art can be contemporary, too. It’s an idea I believe in very much. Mrs Prada read my book, Futuro del Classico [The Future of the Classical] in which I try to imagine what the function of the Classical could be in an era like ours. So I was seduced by her proposal. While it is very common to see an archaeological museum host works of contemporary art, it is not at all common the other way round—that a collection of contemporary art, such as the Prada Foundation, holds a conversation about ancient art as its inaugural exhibition.

It was a real challenge, then?

Definitely. Exhibitions are justified by their concept. I tried to imagine a theme that had some contemporary resonance, and a theme that is very strong in contemporary art is seriality—the production of multiples in series—which also has a great significance in Classical art. We always imagine the Classical as a supreme art of unique, unrepeatable masterpieces. Not so. Classical art had its own seriality, too. There were certain works that would be copied, especially in sculpture. There is an ancient seriality that must be compared to modern seriality. There is a repetitiveness that does not contradict the originality of the singular. That was the idea that gave birth to the Milan exhibition and its simple title: Serial Classic.

And the second exhibition?

That came shortly after. I discussed it with Miuccia Prada and her collaborators, as well as with Germano Celant [the Prada Foundation’s artistic director]. That was the second challenge. My idea was based on the spaces of Ca’ Corner della Regina—sumptuous but domestic spaces that are very different from those in Milan. I imagined how the desire to appropriate the great works of antique sculpture pushed collectors not only to have them copied in numerous replicas but also to have them reproduced at home in miniature form. In this way, one could have a two-metre-high Apollo Belvedere on a small scale—30cm tall, for example. That’s where the idea comes in of the private possession—an object for the studiolo which, from the 15th century in Italy and Europe, produced extraordinary masterpieces. Hence the show’s title, Portable Classic, for this kind of serial reproduction in reduced, pocket-sized form. Next to the three-metre-high cast of the Farnese Hercules, the exhibition will have other Farnese Herculeses ranging from 180cm to 15cm.

Have you ever thought of working on contemporary art?

I can’t be a specialist in everything. Contemporary art interests me very much and occasionally I have worked on it—in particular, with Bill Viola, who is a friend of mine. I wrote an essay about him and have followed many of his exhibitions. But I have never been and never will be a critic of contemporary art; I do not have or presume to have all the necessary knowledge. In organising this exhibition I tried to understand what it meant to produce, say, 25 versions of a work—not perfectly the same but in a similar way. Or, for example, what it meant for Rauschenberg to make two practically identical paintings.

• Serial Classic: Multiplying Art in Greece and Rome, Prada Foundation, Milan, 9 May-24 August

• Portable Classic: Ancient Greece to Modern Europe, Prada Foundation, Venice, 9 May-13 September

• The shows are being co-organised by two former students of Salvatore Settis: the archaeologist Anna Anguissola, now a postdoctoral fellow at the Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich, for Milan, and Davide Gasparotto, the senior curator of paintings at the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, formerly the director of the Galleria Estense in Modena