It’s a chilly Sunday morning outside Leytonstone tube station in a typically socially mixed and slightly ramshackle suburb of east London. Into the station car park rumbles a camper van that has clearly seen as much love as it has done miles. This “battle bus” is going to take us about 30 miles to the west of the capital, to the significantly more affluent home counties parliamentary constituency of Surrey Heath. It is there that the former Conservative education secretary (now chief whip) Michael Gove has been MP for ten years and at the last general election in 2010 had a majority of more than 17,000 votes. The next general election is on 7 May and behind the wheel of the van is a Leytonstone resident and artist who wants to send the incumbent packing; Bob and Roberta Smith, the alter ego of Patrick Brill, has got it in for Gove and he’s standing against him for parliament.

Bob’s not a beginner at drawing attention to the downgrading of art in particular, and the arts in general, in British education. As early as December 2010, in a letter to the Guardian newspaper, he bemoaned the effective privatisation of the UK’s arts schools, citing his painter father’s transformation of Chelsea School of Art from an elite institution into one that maintained a high reputation while nevertheless attracting students from all backgrounds to study a far wider range of visual arts subjects. But that was when education was free and students were given grants to fund them through higher education. Now tuition fees, of up to £9,000 a year, and subsistence loans must be repaid once former students reach a certain level of income.

“Art should be the centre of a national curriculum based on creative thinking… The child who becomes inhibited is inducted into the mediocre majority of the visually illiterate.”

“Mediocre majority”

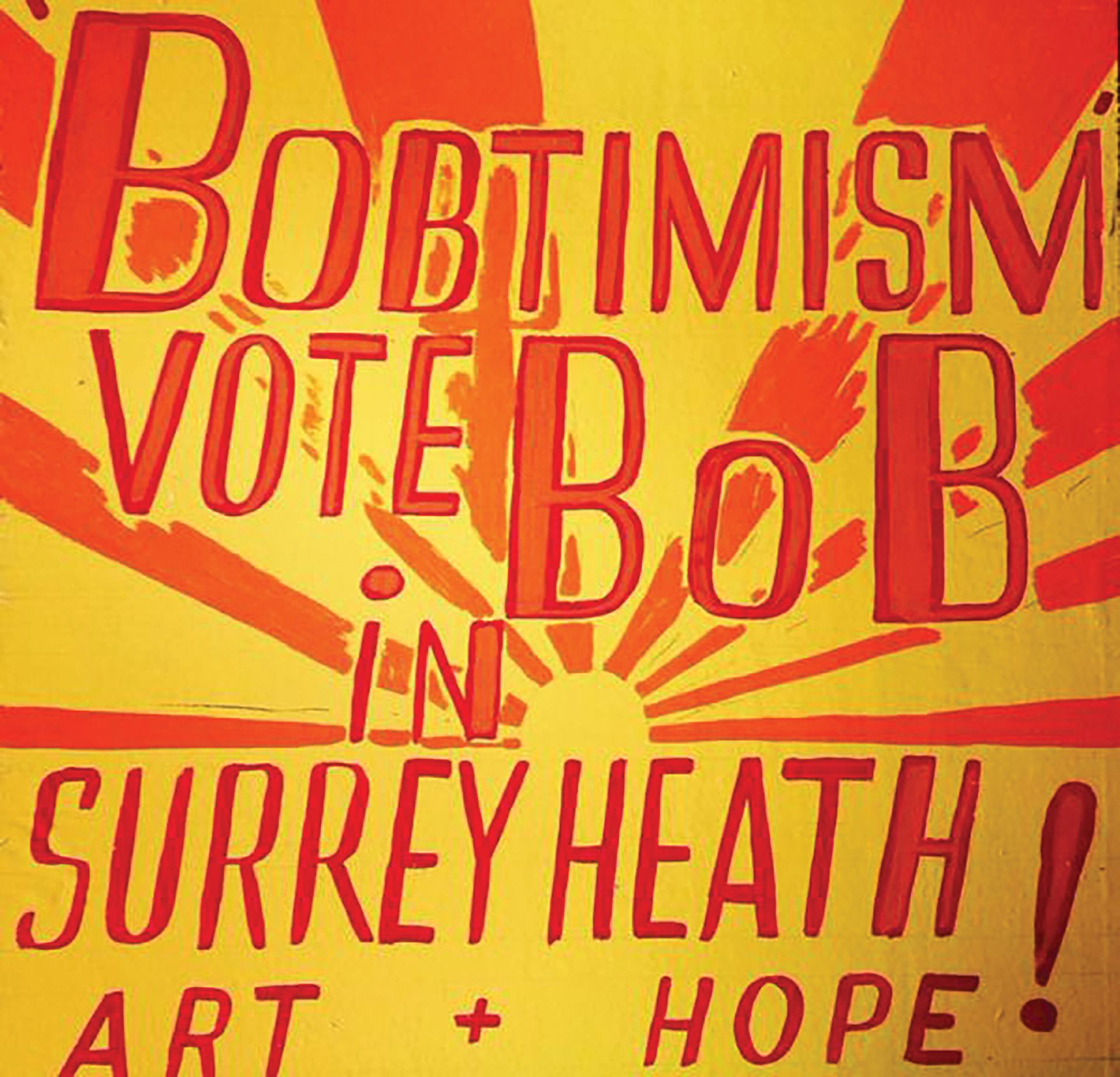

Bob’s work is in a Pop art tradition and most often consists of painted texts or slogans on wood panels or other objects. In the summer of 2011, in response to government policy that would remove creative arts subjects from schools’ core curricula, he painted the work Letter to Michael Gove, headed “Your destruction of Britain’s ability to draw, design and sing” and including the assertion that “Art should be the centre of a national curriculum based on creative thinking… The child who becomes inhibited is inducted into the mediocre majority of the visually illiterate of which you, Michael Gove…are a part.”

A celebratory “Art Party” event in the coastal town of Scarborough came next, followed by a film of the same name, released last summer. And then the declaration that he would stand in the election. Which is why, just over an hour after we set off from London, and after a few missed turns, we assemble in the car park at the train station in Camberley, in the heart of the constituency.

Walk on the mild side For the first event of the campaign, we are to undertake a dérive of the town, an unplanned journey defined by the Situationist cultural theorist Guy Debord as “a mode of experimental behaviour linked to the conditions of urban society: a technique of rapid passage through varied ambiances”. It will be led by the author and film-maker John Rogers who specialises in documenting the lost routes and forgotten buildings of London and other cities. It’s not exactly a tub-thumping political rally but the thought of a crocodile of supporters winding their way through the back streets of Camberley is appealing. Except that there are only five of us: two journalists, Bob, Rogers and one supporter who has also come up from London. From the station platform two young girls ask what we are doing. Bob explains and they are given badges and fliers. Two voters for the next time, perhaps, but right now this small band has Rogers’s instructions to follow.

The specific instructions of the dérive involve taking second right, then second right again, then next left, and then stopping and taking in the surroundings, then repeating the directions. We encounter, among other places, a rather striking electricity substation and the stage door of Camberley Theatre, where Bob makes an improvised speech. Through sheer serendipity, 90 minutes later, we finish at the back entrance of Camberley’s sole art supplies shop.

There may not have been many potential supporters along for the tour, but the group takes it as a promising sign at this early stage of the campaign. Bob also hides a small painting in a bush in the town and tweets that it is a gift to the person who finds it. (A few weeks later, when Rogers has edited a film of the walk for his Drift Report YouTube channel, it gets tweeted by the comedian Russell Brand and retweeted hundreds of times over.)

Just under a week later, in the bar of the independent Shortwave Cinema in Bermondsey, south-east London, there is a fundraising meeting-cum-performance. Bob has enlisted his wife Jessica Voorsanger, a respected artist in her own right, and their daughter to sell books and prints on a stall. After a speech from the campaign manager Matthew, he declaims his manifesto, in painted panel form, slamming each work down firmly on the floor. This time around 20 people pay rapt attention. The numbers are growing, although it’s far from clear how many of them actually have a vote in Surrey Heath.

Lack of commitment Leading politicians, at least those with a chance of gaining power on 7 May, have not given much away in the weeks and months before the vote, almost certainly mindful that the idea of balancing the books is uppermost in the electorate’s minds, no matter how misjudged is the comparison between a household and a national economy. Only the Scottish National Party’s Nicola Sturgeon, of those with any real political clout, has said she will increase public spending. In a speech on the cultural sector given in February, the Labour leader Ed Miliband said that schools would be required to offer arts subjects and opportunities in order to be given an outstanding rating by inspectors. However, he made no commitments to reversing any of the coalition government’s arts funding cuts, including a 30% cut to Arts Council England’s budget made in 2010. For all the deliberate ambiguity between political campaign and work of art, this is what gets Bob’s hackles up.

The next time I see him he’s on television (on the BBC’s Daily Politics show)—arguably a much better way of getting his message across—pointing out the government’s own figures of an arts economy worth around £70bn annually, while Conservative culture minister Ed Vaizey awkwardly brushes aside statistics showing the drop in students taking arts subjects following their downgrading and limiting in schools under the Gove-led education department.

There’s an indicator, however, that he might have done more, earlier, to raise his profile in the constituency when the question comes from the floor: “Are you actually an artist?”

One-man political rapid-response unit On the local television station London Live, there is a spat with Arts Council England boss Peter Bazalgette, who suggests that Bob would have him lose his job. A few days later, at the opening of the Vote Art poster competition show at Peckham Platform in south London, Bob’s already painted Bazalgette’s P45 employment termination form—a one-man political rapid-response unit.

Finally, there is an audience of hundreds at the hustings, in April, in a church hall in Camberley. Gove himself is there, along with most of the other candidates, and Bob gets an early and rousing cheer when he says in his opening statement that he is there and standing in order to counter Gove’s limiting of the education curriculum (continued by his successor as education secretary, Nicky Morgan). The artist-candidate gets in a few good political jabs about the need for a curriculum that addresses digital art forms that need people who are both good at maths and good at drawing, and even suggests that the voting age could be lowered to 14, mindful perhaps of the two potential supporters on the station platform. There’s an indicator, however, that he might have done more, earlier, to raise his profile in the constituency when the question comes from the floor: “Are you actually an artist?”

“I am… I’m a Royal Academician,” he says, showing the medal he was given by the academy in 2013 (he was also a trustee of the Tate between 2009 and 2013). If Tim Cross, a retired major-general and former government military adviser who is chairing the hustings, is aware that medals are awarded to artists, he’s not giving anything away and moves the conversation on.

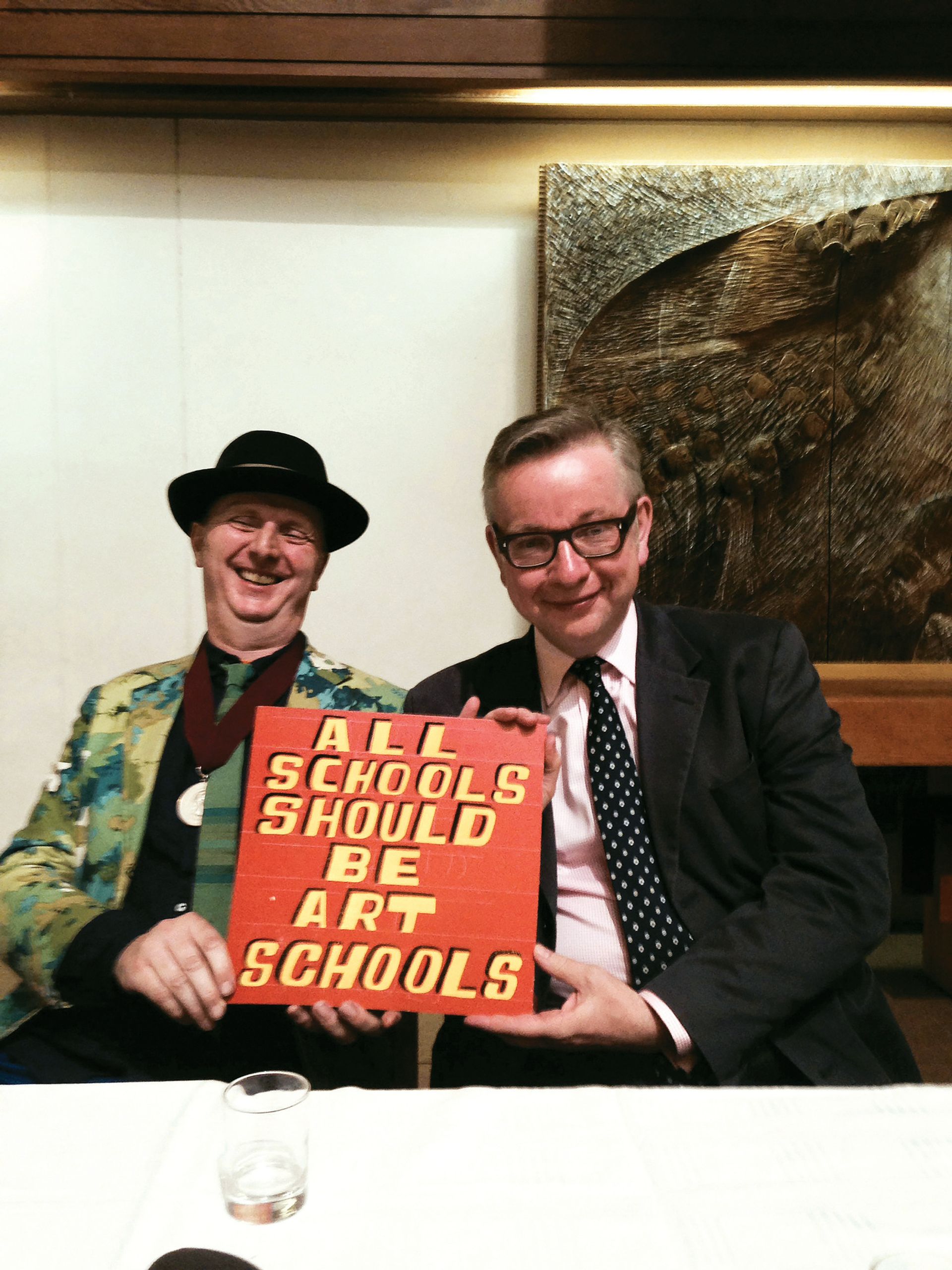

Gove gets the message? Surprisingly, Gove seems quite happy to pose for a photograph with Bob, holding a painting that declares “All schools should be art schools”. Was he too tired to notice? Or has he calculated that such is the security of his vote in Surrey Heath that, by appearing with Bob and with that slogan, it might seem that he is actually a supporter of more art for schools? One Westminster village rumour has it that if the Conservatives are returned to power on 7 May, Gove is being lined up as chancellor of the exchequer, with further and as yet unspecified swingeing cuts to be made to fund manifesto promises on housing and inheritance tax. So maybe all publicity is good publicity.

At this point, The Art Newspaper has to leave the campaign trail in order to get to press on time. So, with a few weeks to go, what is his target? How many votes will count as a success? Voorsanger, no dutifully deferential political spouse, nevertheless makes a very devoted promise: “If he gets into triple figures, I’ll bake him a cake.”

Perhaps he might make that milestone. Who, after all, would argue against more art in schools? For trying to make that happen and for drawing attention to the decline of art in schools with such passion and wit, Bob at least deserves a cake.

• Bob and Roberta Smith: Why I Am So Angry, Handel Street Projects, London, until 9 May

• The candidates for the Surrey Heath constituency are: Laween Atroshi, Labour; Ann-Marie Barker, Liberal Democrat; Juliana Brimicombe, Christian Party; Paul Chapman, Ukip; Michael Gove, Conservative; Kimberley Lawson, Green Party; and Bob and Roberta Smith, Independent