For anyone interested in Dutch art, the new, extensively revised second edition of Seymour Slive’s classic monograph, Frans Hals, is cause for celebration. Alas, Professor Slive never saw the finished product: he died on 14 June 2014, three months before his 94th birthday. The memorial service held at Harvard University, where Slive taught art history from 1954 until 1991 (when he became professor emeritus), drew family, friends, former students and colleagues from England, the Netherlands and all over America.

Ideal interpreter

Slive was such a colourful and energetic character that he would have been a perfect subject for Hals, while the painter found his ideal interpreter in Slive. Scholars of his generation, not to mention disposition and experience—Slive was the director of Harvard’s Fogg Museum from 1975 until 1982 and then the founding director of the Harvard Art Museums—were much more inclined to study actual objects than are academic art historians more recently trained, with obvious exceptions (including many of Slive’s former graduate students). And Slive as teacher and author represents other approaches as well, as seen in his first book, Rembrandt and His Critics, 1630-1730 (1953); in his grand survey, Dutch Painting 1600-1800 (1995); and in his many articles (which include iconographic studies).

His career as a connoisseur, as applied to critically cataloguing an artist’s work, was above all devoted to Hals, although Slive took on two more giants of the period in his monumental volume Jacob van Ruisdael: a Complete Catalogue of His Paintings, Drawings and Etchings (2002), and in his corpuses of Rembrandt drawings (1965 and 2009).

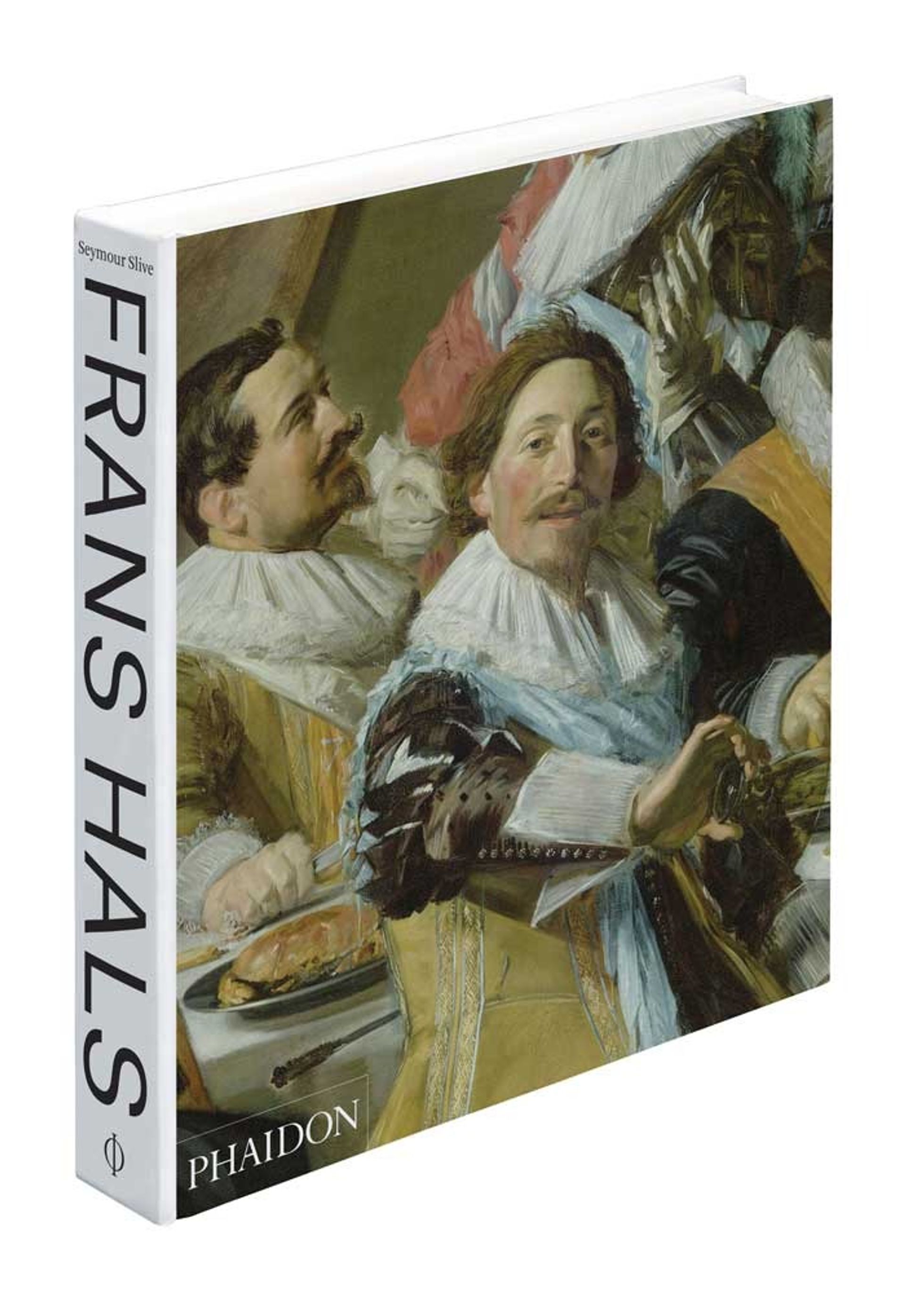

The first edition of Frans Hals was published in London by Phaidon between 1970 and 1974 (the text and plate volumes appeared in 1970 and the catalogue four years later). The catalogue entries of 40 years ago range from about a half-column to a few pages in length, depending mostly on how much discussion follows the records of provenance, exhibitions and some essential bibliography. This is important to know, since the 1974 catalogue of about 220 accepted works, 20 lost pictures and about 80 rejected or “problematic” paintings, as well as data on numerous copies and variants of works in the four categories, has not been revised in the second edition. The captions to the 233 colour plates (when not details) cite the present owner, but when, as often, it was “private collection” in 1974 and again in 2014, the reader has no way of knowing whether the painting was saved by the elderly Lady Mary for Downton Abbey or (like the precious portrait on copper of Samuel Ampzing) has been in three different New York collections since his lordship (in this case Harold Samuel) sold it in 1975.

Some of Slive’s colleagues will recall that, in the early days of the new Hals project, there was talk of an online catalogue, and they enjoyed the image of something like a cog railway ascending into the digisphere. But this plan was dropped, for reasons best known to the publishing industry. Nor would the present volume have appeared in its richly illustrated but affordable form—physically, it is something like half Ernst van de Wetering’s A Corpus of Rembrandt Paintings VI (2014) for less than a tenth the price—had not dozens of Slive’s friends, colleagues and admirers raised more than $100,000 to make it happen. As a consequence, each accepted painting by Hals is reproduced in colour twice: as a large plate and as a small illustration on the page where it is discussed. In the first edition only comparative photos appeared in the text volume (these are now newly sel ected and far more numerous), and the entire plate volume was without colour.

Subtle changes

Readers who have the first edition of Frans Hals on their shelves might compare the introductory chapter or particular pages of the other six and conclude that little in the text has changed. But there are subtle rewordings throughout, and significant revisions or expansions here and there (for example, two new paragraphs on prints after Hals’s portraits). In the introduction, the marriage of Hals’s parents in Antwerp “must have occurred by April 1582”, whereas it was “1581 or later” in the first edition. Slive has also reined in some of the loose asides that many readers would have found entertaining in the 1970s. In the first edition the remark that Hals’s parents were possibly “lax about publishing their marriage banns” is followed by the crack that “the Hals family never won a reputation for rigorous moral standards”. Archivists and historians could offer several reasons why such a light touch should be painted out and Slive deserves credit for doing so.

There are also many signs of keeping up with the literature: for example, a footnote recommending “Ekkart 2014” on the subject of portrait drawing, which the new edition’s extensive bibliography reveals to be an essay in the catalogue of the Johannes Thopas exhibition in Aachen and Amsterdam. More predictably, an alternative attribution of Hals’s Banquet in a Park, around 1610, (destroyed in the Second World War), suggested in Christopher Atkins’s book The Signature Style of Frans Hals (2012), is noted and rejected. Nonetheless, Atkins’s study makes a fine companion to the updated Slive. But if the reader wants one rather than six books on Hals then the new Slive is the right choice.

Small, perfectly formed

A very different, small book for a broad audience is Antoon Erftemeijer’s Frans Hals: a Phenomenon. It comes from the Frans Hals Museum and is a “wholly revised, updated and greatly enlarged version” of the author’s Frans Hals in the Frans Hals Museum of 2004. Erftemeijer is a specialist in 19th-century painting (and a curator of Modern art) and in a way this is appropriate to the task at hand, which is more an appreciation of Hals than a history of his life and work, with a critical discussion of his style and significance in the 17th century (for that, one might turn to my own Frans Hals: Style and Substance, which was the summer 2011 issue of The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin).

Erftemeijer’s assumed reader is not someone who routinely reads art-historical texts but a visitor to the Frans Hals Museum who wants to know a bit more about the artist, his time and place, and about related issues such as the use of canvas or wood for supports, priming and other basic technical issues, workshop pictures, and whether there is truth to the rumour that Hals drank. Around 70 of the 168 pages are given over to good colour illustrations, and 14 are devoted to Hals’s artistic admirers and his reputation from around 1700 onward. The bibliography seems meant to impress rather than inform since it includes dozens of publications in four languages, some of them quite specialised.

Frans Hals

Seymour Slive

Phaidon,

400pp, £75 (hb)

Frans Hals: a Phenomenon

Antoon

Erftemeijer

Nai010 Uitgevers, 168pp, €15 (pb)

Walter Liedtke was the curator of European paintings at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. He was the author of the museum’s catalogue of Flemish paintings (1984), Dutch paintings (2007), a Vermeer monograph (2008), and various exhibition catalogues. He was killed in a railway accident in New York on 3 February.