"Moreau’s diverse and often paradoxical oeuvre lies at the crossroads of apparently contradictory trends in 19th-century art”, Peter Cooke observes at the end of his monographic study of Gustave Moreau (1826-98). Often described as a proto-Symbolist—and less often as a history painter—Moreau has proved hard to classify. The best of his elaborate biblical and mythological tableaux are hauntingly memorable but they are difficult to decode. Gustave Moreau: History Painting, Spirituality and Symbolism succeeds in illuminating a very peculiar and compelling figure on the margins of French art.

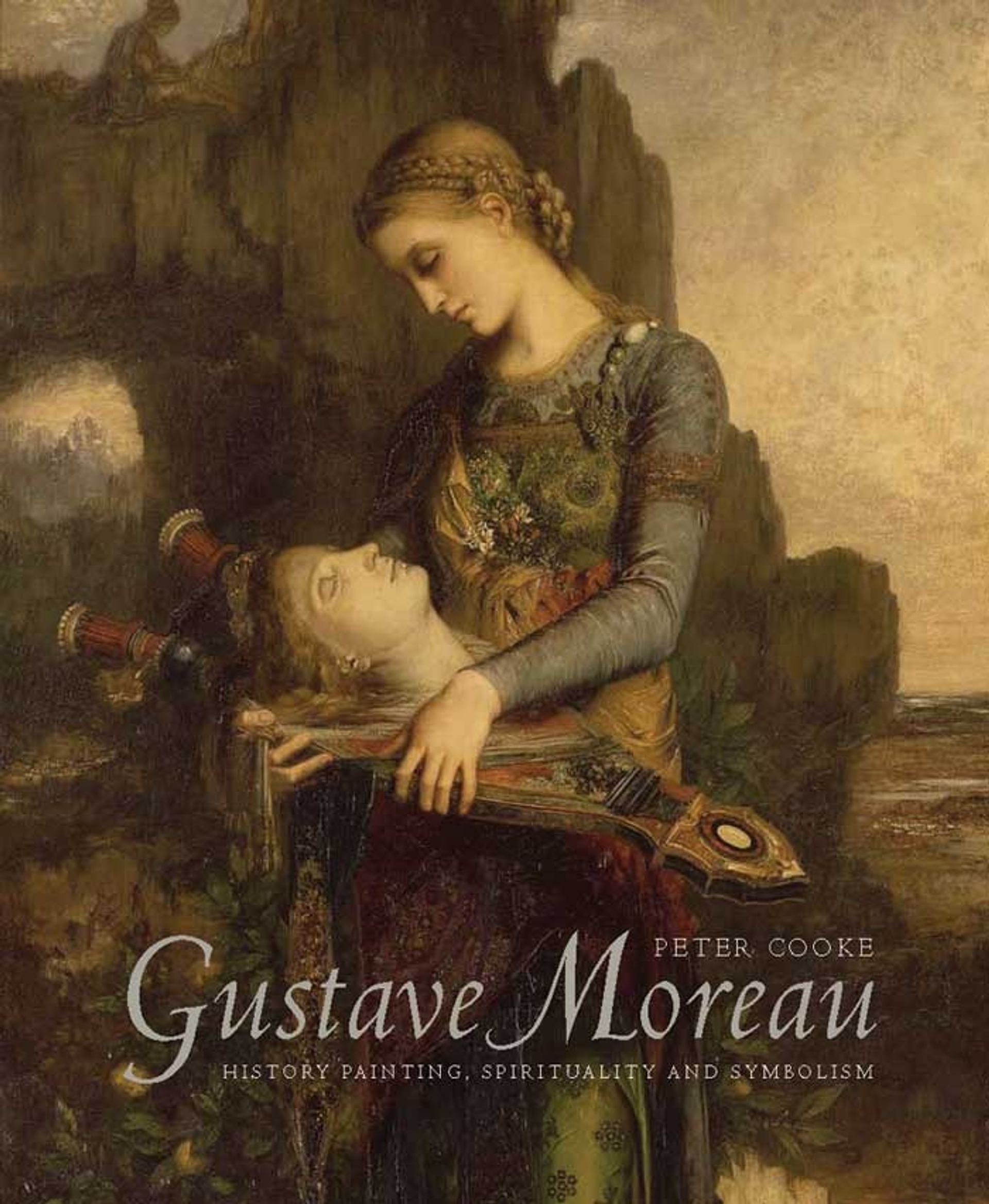

Moreau’s classic oil compositions feature figures in isolated areas of light surrounded by large areas dark enlivened with coloured highlights, bestowing these grottoes and throne rooms with a bejewelled appearance. The expressions of the characters are restrained and their gestures anti-naturalistic and hieratic. Intricate decoration covers garments and architecture, causing paintings to exude a pseudo-organic quality.

By the end of the Second Empire salon history painting had sometimes become an exercise in sensationalism, titillating with visions of gratuitous horror and nudity. It is difficult not to see Moreau as—to some degree—wilfully martyring himself by adhering to the history-painting tradition which he suspected was moribund. Moreau’s art falls between the Neo-Classical approach to history painting, which he seemed to be temperamentally and intellectually unsuited for, and the emergent Symbolist movement, which the painter considered insufficiently grand. Moreau’s highly complex and eclectic outlook combined a devotion to art of ages past with pantheistic mythology and a strain of Catholic mysticism. Moreau’s position as an anti-realist stemmed from an attachment to idealism. His politics were staunchly monarchist and nationalist.

Cooke suggests that negative reviews for Moreau’s Salon pieces after the success of his Oedipus and the Sphinx (1864) were due to the mixing of styles and the problematic legibility of pictorial narratives in Moreau’s canvases. Moreau used Neo-Classicism as the basis of his approach but also incorporated the emotive colouring of Romanticism and the ornamentation of Far Eastern and Islamic art. Cooke compares Moreau’s paintings to those of others exhibited in the Salon of the same year. This is instructive as many of these paintings are by artists now little known and the paintings themselves are lost or relegated to the storerooms of provincial museums.

An unheeded prophet

The mixed reception his salon pieces received contributed to Moreau’s perception of himself as an unheeded prophet. To secure his position for posterity, Moreau transmitted his principles to numerous students. He also worked on paintings which he intended for a posthumous museum dedicated to his art. While he had no successors among his students, Moreau’s house-museum in Paris has proved a more enduring legacy. Moreau apparently made versions of his most successful canvases specifically so they could be preserved at the museum. It is from the archives of that museum that Cooke has gleaned much of the information presented in this volume.

As a teacher at the École des Beaux-Arts, Moreau came into contact with a generation of artists who would later shape Modernism. Students Matisse, Marquet and Camoin would later form the core of the Fauves, who opposed the professors’ ideals. Cooke uses first-hand testimony to demonstrate that Moreau was a sympathetic teacher who recommended copying a broad variety of art and who left a strongly favourable impression on pupils. Only Rouault, alone among the major pupils of Moreau, became a painter of allegories and in any sense an anti-realist.

Cooke gives a sympathetic overview of the painter’s intentions, presenting new evidence and summarising research conducted during recent decades. The book includes sections discussing Moreau’s museum and his nearly abstract sketches. When these watercolour composition studies came to the attention of American critics during the heyday of Abstract Expressionism, Moreau was acclaimed as a forerunner of modern abstraction. These were working studies and experiments intended to assist figure paintings and Moreau did not formulate or advocate anything we could describe as aesthetics of abstraction. Moreau was modern in respect to his finish, which became looser and rougher, in contravention of the glassy finish expected of salon aesthetics.

Moreau was the last advocate of a tradition that later artists decisively turned away from. Moreau’s art is easily interesting and sophisticated enough to deserve the overdue attention that Cooke has paid it.

Gustave Moreau: History Painting, Spirituality and Symbolism

Peter Cooke

Yale University Press, 252pp, £45, $75 (hb)

Alexander Adams is a British writer and art critic. His most recent book of poems and drawings The Crows of Berlin was published this year by Pig Ear Press.