More than any other naturally occurring substance employed for the making of sculpture, ivory is a law unto itself. In the European tradition, the overwhelming majority of ivories have been carved from the tusks of African elephants, but the term is also commonly applied to walrus ivory (also known as morse), narwhal “horns”, bone and other related substances. In all, the physical characteristics of the raw material simultaneously inspire and constrain the design of the work, and with experience it is often possible to “see” the underlying form behind the finished object, perhaps especially when looking at the productions of the Gothic and Baroque periods. For some reason, but by no means necessarily this one, both were Golden Ages in the history of ivory production, whereas the Renaissance—in this context, and almost no other, a low between two highs—was absolutely not.

If ivories are allowed to enjoy Golden Ages, then so of course are books on ivories, although in this instance the age turns out to have lasted for two decades or so, arguably peaking in the last couple of years with the publication of the three works under review here. They are all models of traditional object-based scholarship, and serve as a timely and uplifting demonstration of the value not only of the collection catalogue but also of the catalogue entry, at a time when the latter in particular is increasingly under threat, admittedly above all in the catalogues of temporary exhibitions.

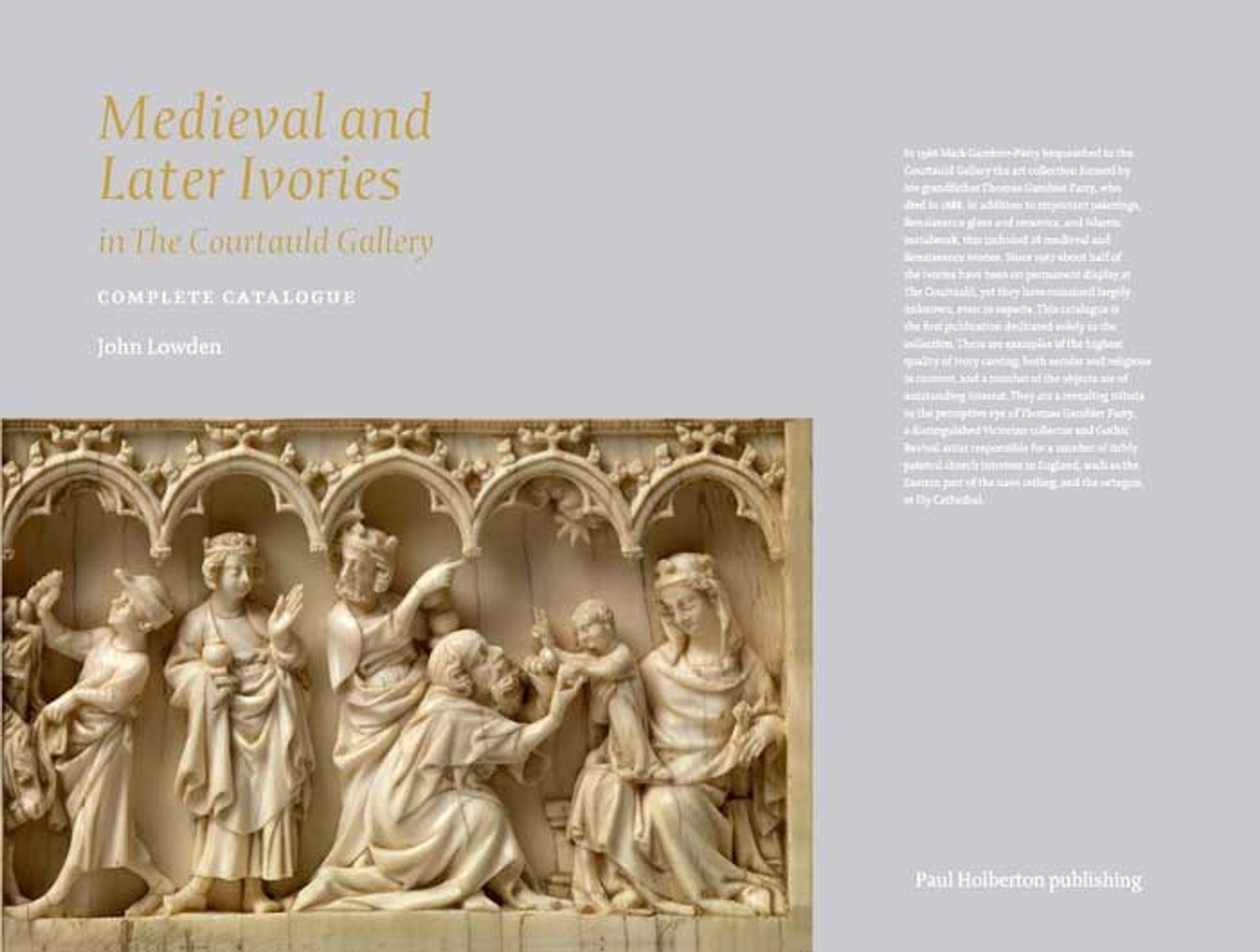

John Lowden’s Medieval and Later Ivories in the Courtauld Gallery: Complete Catalogue runs to a modest 28 numbers, including a single 19th-century fake and three items that have been missing since November 1982, but the best of the pieces, such as a superb Parisian Passion diptych of around 1350-75, are very fine indeed. All the stars come from the Gambier Parry collection, which is also the subject of an absorbing introductory essay by Alexandra Gerstein, and are accorded deservedly detailed consideration.

The Courtauld is the home of the online Gothic Ivories Project, which represents a brilliant achievement on Lowden’s part, and comprises more than 3,100 ivories, of which there are around 9,000 images. It builds on, and far surpasses, the pioneering work of Raymond Koechlin, whose Les Ivoires Gothiques Français of 1924 was hitherto the bible of this branch of medieval ivory studies. The project’s extraordinary value is handsomely acknowledged by Paul Williamson and Glyn Davies in their monumental double-decker Medieval Ivory Carvings: 1200-1550 (289 entries from the Victoria & Albert Museum’s collection), which is the follow-up to Williamson’s Medieval Ivory Carvings: Early Christian to Romanesque of 2010. A crucial weapon in their armoury has been radiocarbon dating, which has allowed the authenticity of a small selection of pieces to be vindicated, while others have been exposed as later (usually 19th-century) counterfeits.

Williamson and Davies cover a remarkably wide range, not just in terms of chronology and geography, but also in terms of artistic importance and quality. Little boxes and combs cohabit with such towering masterpieces as Giovanni Pisano’s The Crucified Christ, 1285-1300, or the Soissons and Salting diptychs, and all are accorded appropriate attention, the latter on occasion having virtual mini-monographs devoted to them.

It seems important to add that, whereas most catalogues are almost inevitably largely exercises in the adroit synthesis of current opinion, this one is exceptionally full of groundbreaking new research, and seems bound to have almost as transformational an effect on the study of Gothic ivories as did Koechlin in his day.

In terms of its arrangement, the items are divided into the religious and the secular, and then further subdivided by type and subject matter, so, for instance, all the figures of the Virgin and Child are grouped together, but so are all the mirror backs. One of the striking features of the V&A’s holdings in this area is their internationalism, but seen en bloc they also underline the extent to which Gothic ivory sculpture is an art form dominated by the relief, with only the occasional figure in the round. No less striking is the fact that secular themes, notably those drawn from the world of courtly romance, are far more common than in almost any other artistic domain.

Sheer variety

It is no coincidence that Williamson and Davies’s catalogue follows hot on the heels of Marjorie Trusted’s Baroque and Later Ivories, with the result that all the V&A’s European ivories are now fully catalogued. Again the text is highly authoritative and the statistics daunting, with a whopping 506 entries. The material is mostly organised by country, except for categories such as snuff rasps and cutlery handles. It is probably fair to say that in this area the V&A cannot quite compete with the most illustrious royal and princely collections on the Continent, which were built up at the time the works were being manufatured, but this does mean that there is more variety than almost anywhere else. What is certain is that the representation of a major figure such as David Le Marchand, born in Dieppe but British by adoption, is without equal.

A perhaps surprising number of Baroque ivories, and not just reliefs, are based on prints. It is a mark of Trusted’s meticulousness that this reviewer could spot only one and a half Homeric nods: Descent from the Cross by Richard Cockle Lucas, 1851, is a dead ringer, in reverse and no doubt via a print, for a painting by Rembrandt in the Alte Pinakothek, Munich, while a statuette of Death as a Drummer, around 1670, perhaps by Joachim Henne, is surely inspired by a corresponding figure in one of the woodcuts of Holbein’s Dance of Death.

Medieval and Later Ivories in the Courtauld Gallery: Complete Catalogue

John Lowden

Paul Holberton Publishing, 144pp, £40 (hb)

Medieval Ivory Carvings: 1200-1550

Paul Williamson and Glyn Davies

V&A Publishing, 928pp,

two vols, £150 (hb)

Baroque and Later Ivories

Marjorie Trusted

V&A Publishing, 544pp, £85 (hb)

David Ekserdjian is the professor of art history at the University of Leicester and an authority on Italian Renaissance painting with particular specialities in the artists Correggio and Parmigianino, the subjects of his two Yale monographs of 1998 and 2006. He is also an expert on the history of collecting. With Cecilia Treves, he organised the 2012 exhibition Bronze at the Royal Academy.