The other day, it was raining in Bloomsbury, central London, and I had half an hour to kill between appointments. So I nipped into the British Museum. This is a traditional use of the vast building, as described in countless novels. But the atmosphere inside has changed. Where once you would have found a place of quiet scholarship, its empty halls resounding to the footsteps of an occasional incursion, you now walk into a bustling space that is so full of people and activity that it has replaced the theme park Alton Towers as Britain’s favourite attraction.

This is part of the Neil MacGregor effect. When he became director of the British Museum in 2002, he inherited an institution that was in trouble. The rebuilding of the Great Court had been completed, creating the largest covered public square in Europe, but the repercussions of budget and time over-runs were still being felt. The exhibition programme was old-fashioned and confused.

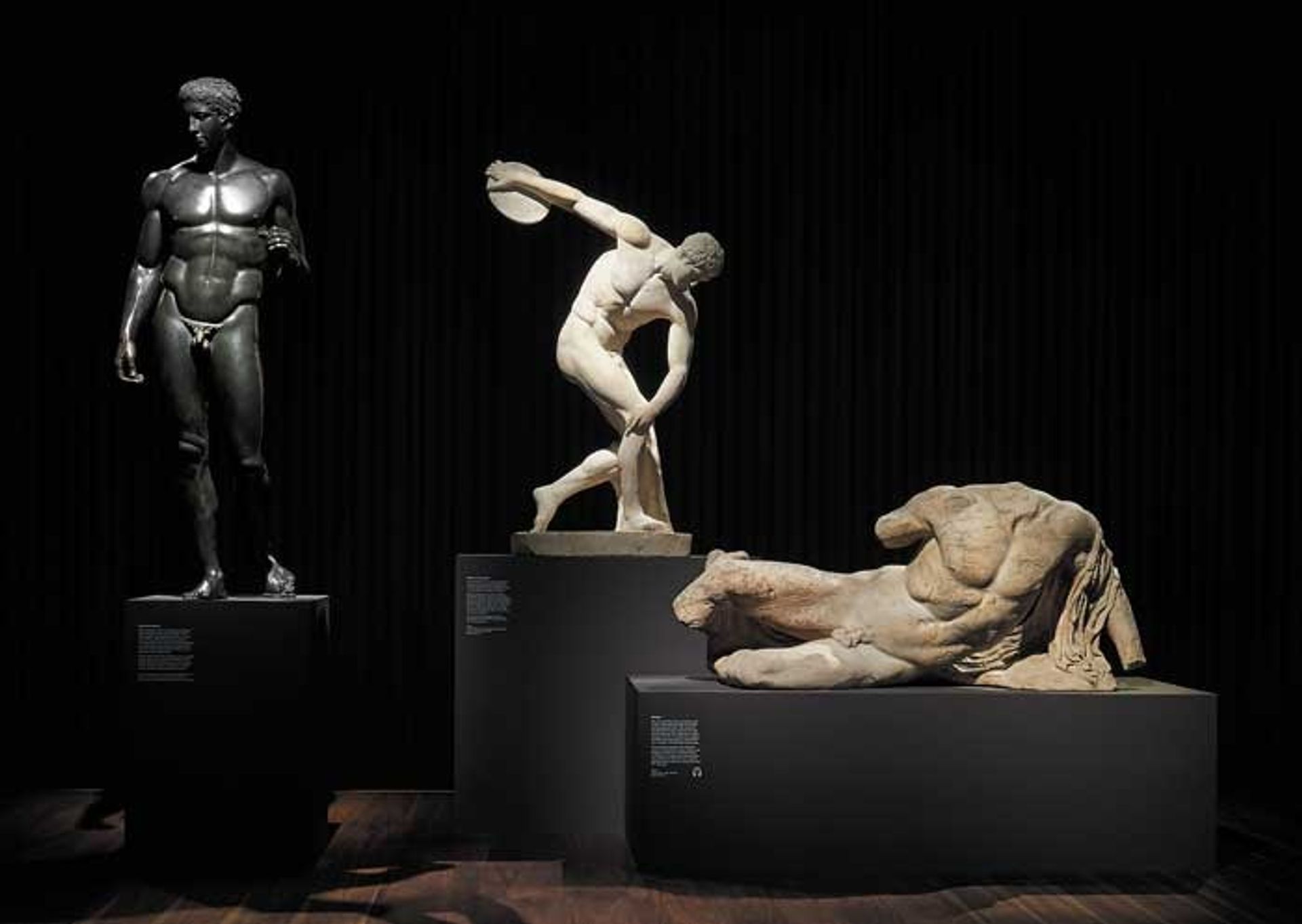

Thirteen years later, the British Museum’s position as a world leader cannot be challenged. Visitor numbers have risen from around four million to 6.7 million, second only to the Louvre. Shows such as Hadrian: Empire and Conflict (2008); Hajj: Journey to the Heart of Islam (2012); Life and Death in Pompeii and Herculaneum (2013); and the current Defining Beauty: the Body in Ancient Greek Art (until 5 July) have been both scholarly and popular, academic and approachable. Success has eliminated the £5m deficit.

Perhaps best of all, MacGregor has helped the British Museum to define its purpose. As Charlotte Higgins explained in the Guardian: “No one else has so strongly affirmed the notion that our cultural institutions—especially our free national museums—are places in which the citizenry may gather as equals to understand our differences, to seek enlightenment about the historical forces that have formed us, and to grasp Britain’s interconnectedness with the world.”

“Neil’s work has been astonishing. He has taken us on a road that brings revelation and knowledge, and that is why we owe a huge debt of gratitude to him.”

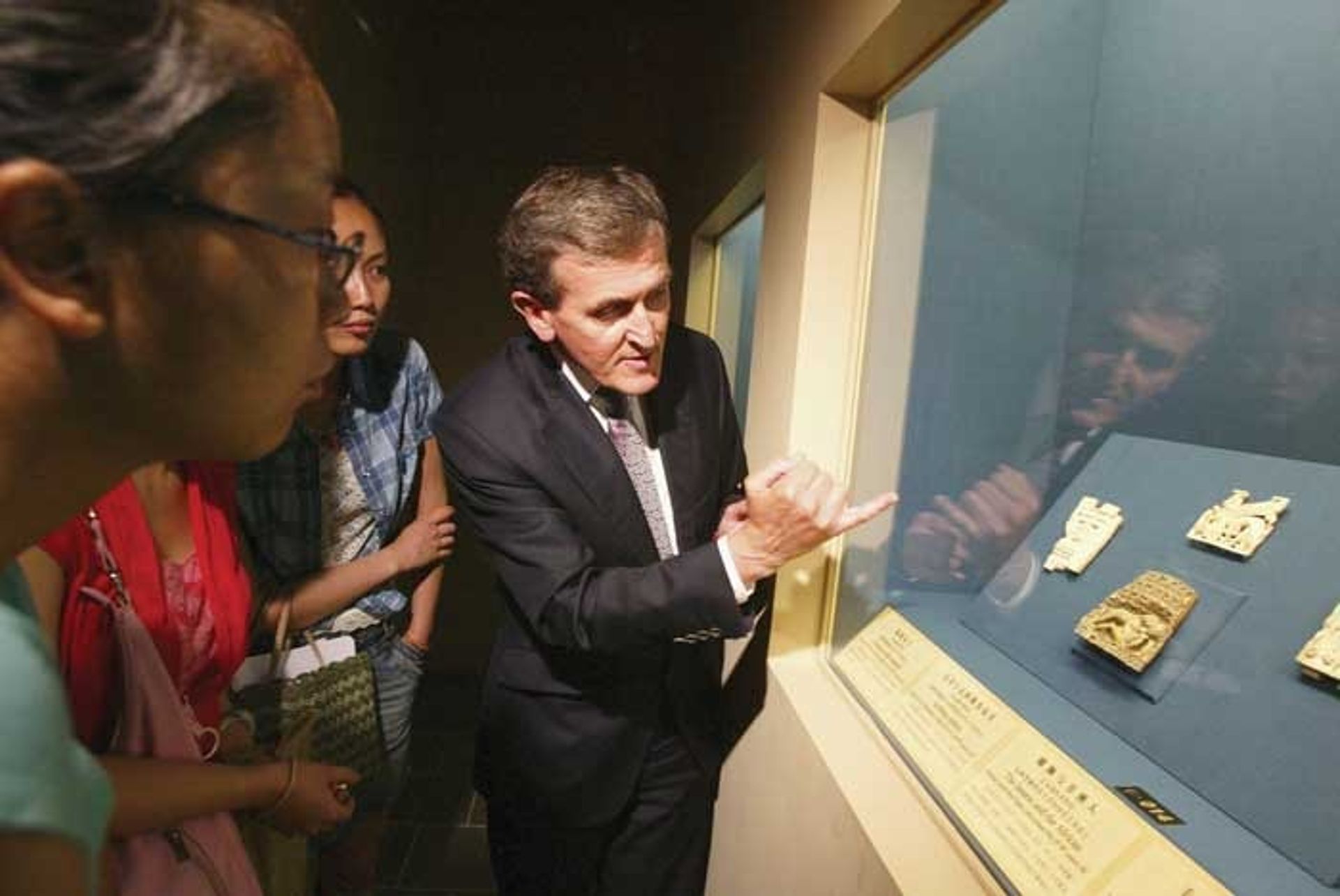

Humane curiosity He has done this both by his directorship of the museum itself, and by broadcasts such as A History of the World in 100 Objects (the 100-part radio series that has now been downloaded 40m times, available at www.bbc.co.uk), which have shared the same humane curiosity, generous intelligence and—most rare of all—the ability to communicate complicated thought in language everyone can understand. Peter Bazalgette, the chair of Arts Council England, says: “Neil’s work has been astonishing. He has taken us on a road that brings revelation and knowledge, and that is why we owe a huge debt of gratitude to him.”

The sense of excitement MacGregor has generated is one reason why the news that he is to step down at the end of the year, with his 70th birthday looming, has caused such a shockwave in the art world. His decision to retire from full-time employment—to do more broadcasting, and advise Berlin’s Humboldt-Forum and a project on world cultures in Mumbai on their futures—can hardly be a surprise, but it signifies a sea change.

A great generation of museum directors is moving on. In London, Sandy Nairne is leaving the National Portrait Gallery; Nicholas Penny is stepping down at the National Gallery. Persistent rumour suggests that Nicholas Serota will depart from the Tate when the new Tate Modern building is completed next year. Though very different individuals, they share certain qualities. Richard Dorment, who has been the art critic of the Daily Telegraph for almost exactly the same 30-year period as these men have dominated the cultural landscape, notes that all are trained art historians: “They understand the importance of scholarship, and running an institution that stages important exhibitions and publishes significant catalogues.”

‘Box-office magic’ They have combined this with a desire to share their knowledge. Even Penny, who more than most harks back to a time when the museum director closed his door and concentrated on writing learned books, has staged shows of Leonardo da Vinci (2011-12) and Rembrandt (2014-15) that have become the most popular in the National Gallery’s history. Dorment calls them “impresarios”, men who turned the heavy sea containers of British culture around mid-course, making them glamorous and vibrant. “MacGregor was box-office magic,” he says. “He is a genius at communication.”

All the directors have also operated in a balmy climate, one that was receptive to their ambition to make art genuinely available to all. Their rise to positions of influence in the late 1980s—MacGregor became director of the National Gallery in 1987; Serota took over Tate in 1988; Nairne was appointed director of visual arts at the Arts Council in the same year—coincided with the first stirrings of the great explosion in British art spearheaded by the Young British Artists. Art was suddenly talked about in the same breath as politics; people might hate it, but it mattered.

In this context, crucially, all have been the beneficiaries of an unprecedented period of financial largesse in British culture. Museums in the 1990s were in a terrible physical state. Stephen Deuchar, formerly the director of Tate Britain and now the director of the Art Fund, remembers that in his early years as a curator in the 1980s it was a struggle simply to get the gutters mended; Liz Forgan recalls looking down on the roof of the National Gallery and seeing gaffer tape keeping out the elements. Then, John Major, the Conservative prime minister, launched the National Lottery and its spending arm, the Heritage Lottery Fund, of which Forgan later became chair. From 1994, there was cash not only to repair buildings, but to transform them, with a great programme of refurbishment and expansion. “It was a huge turning point in the history of British museums,” Deuchar says.

The arrival of the Labour government in 1997 brought more good news for the arts: a period of stable, guaranteed public investment. Forgan says: “The combination of the Tories’ vision of the lottery and Labour’s sustained funding meant that for a magic moment there was a recognition of how important the arts are, and a solid platform on which to plan for the future.”

Hostile conditions This time of plenty has already come to an end. Regional museums are labouring under the double burden of cuts in central and local authority funding; the national museums and galleries directly supported by the Department for Culture, Media and Sport have suffered a 20% cut over the past five years. The trend worries Forgan: “We can’t live on the investment of the past, yet we’ve been doing that for the last three or four years, and the trouble with culture is you can’t turn the tap on and off. Investment needs to be sustained.”

Perhaps it is that sense of contraction replacing expansion that underlines the feeling that the departure of Neil MacGregor and his peers is somehow more significant than the simple passing of the baton to a new generation. The incoming directors will be operating and planning in different and more hostile conditions, though Peter Bazalgette—while continuing to campaign for better government funding—is anxious to emphasise that “tough times get you thinking”. He adds: “The new generation will build on what Neil and the others have done.”

The initial signs are encouraging. The appointment of Gabriele Finaldi to take over the National Gallery brings back to London a 49-year-old scholar whose book The Image of Christ, first published in 2000 while he was a curator at the National, was written with MacGregor. As deputy director of the Prado, Finaldi has been part of the reinvention of a fairly moribund institution into a thriving modern museum. At the National Portrait Gallery, the choice of Nicholas Cullinan, from the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, and before that the Tate, to replace Nairne also looks inspired. The 37-year-old already has a formidable track record as a curator and has long been touted as someone to watch.

“The new generation will need to be skilled in curatorship but also have the breadth and the vision to keep on serving the widest possible public.”

Names bandied around The names being bandied around to replace MacGregor include Maria Balshaw, who has just overseen the rebirth of Manchester’s Whitworth art gallery as a dynamic centre for contemporary art; Diane Lees, who has brought new life to the Imperial War Museum; and Tim Knox, who has only recently moved to the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge but is already mounting outstanding exhibitions. On the other hand, the candidates may just as easily come from the field of archaeology; MacGregor was initially regarded as an odd choice because of his background in art.

After 13 largely glorious years, those early doubts seem like madness—he now looks an impossibly hard act to follow. But as Stephen Deuchar points out “institutions evolve and adapt. Great people retire and are replaced by young people who become equally great.” Yet he acknowledges that some priorities may have to be reset. The Tate, for example, now raises more than 60% of its own income, which makes it not only a huge gallery, but also a big business.

“The new generation will need to be skilled in curatorship but also have the breadth and the vision to keep on serving the widest possible public,” he says. “I am wholly optimistic that there are the directors of the future out there who will do just that.”

The implication is that the next generation will have to be as inventive and assiduous in fundraising as they are in exhibition planning and scholarship. To some extent this is already true; certainly MacGregor has been remarkably successful in finding new sources of finance. But as his example shows, it is the combination of good judgement, sound and deep learning, and entrepreneurial flair that makes a really outstanding leader. As Richard Dorment says: “Being successful always has to do with energy and with understanding the core values of the museum. If you get those two things right, then everything else will follow.”