Invisible Beauty, Iraqi pavilion

Latif Al Ani, Akam Shex Hadi, Haider Jabbar, Rabab Ghazoul, Salam Atta Sabri

Unsurprisingly, the Iraqi pavilion reflects the rise of the terrorist group Islamic State (IS) and the effects of years of war and instability in the country. The Ruya Foundation for Contemporary Culture in Iraq, a non-governmental body, is responsible for the pavilion, housed at the Ca’Dandolo. The curator Philippe Van Cauteren, from SMAK (the Municipal Museum for Contemporary Art) in Ghent, has sel ected five artists working in Iraq and abroad. They include Cardiff-based Rabab Ghazoul, whose performance focuses on the Chilcot Inquiry, the British investigation into the 2003 invasion of Iraq, and Haider Jabbar, a refugee working in Turkey, whose 2,000 watercolours include images of men murdered by IS. “He considers his life needlessly ruined by decades of conflict; he is haunted by what has happened,” says Tamara Chalabi, the chair of Ruya. The show includes two photographers, Akam Shex Hadi (below, Untitled, 2014-15) and Baghdad-based Latif Al Ani, who has captured the streets of the Iraqi capital from the late 1950s to the present day. “Each of the artists has a compelling story to tell. And in the horror and despair, beautiful things are being made,” Chalabi says.

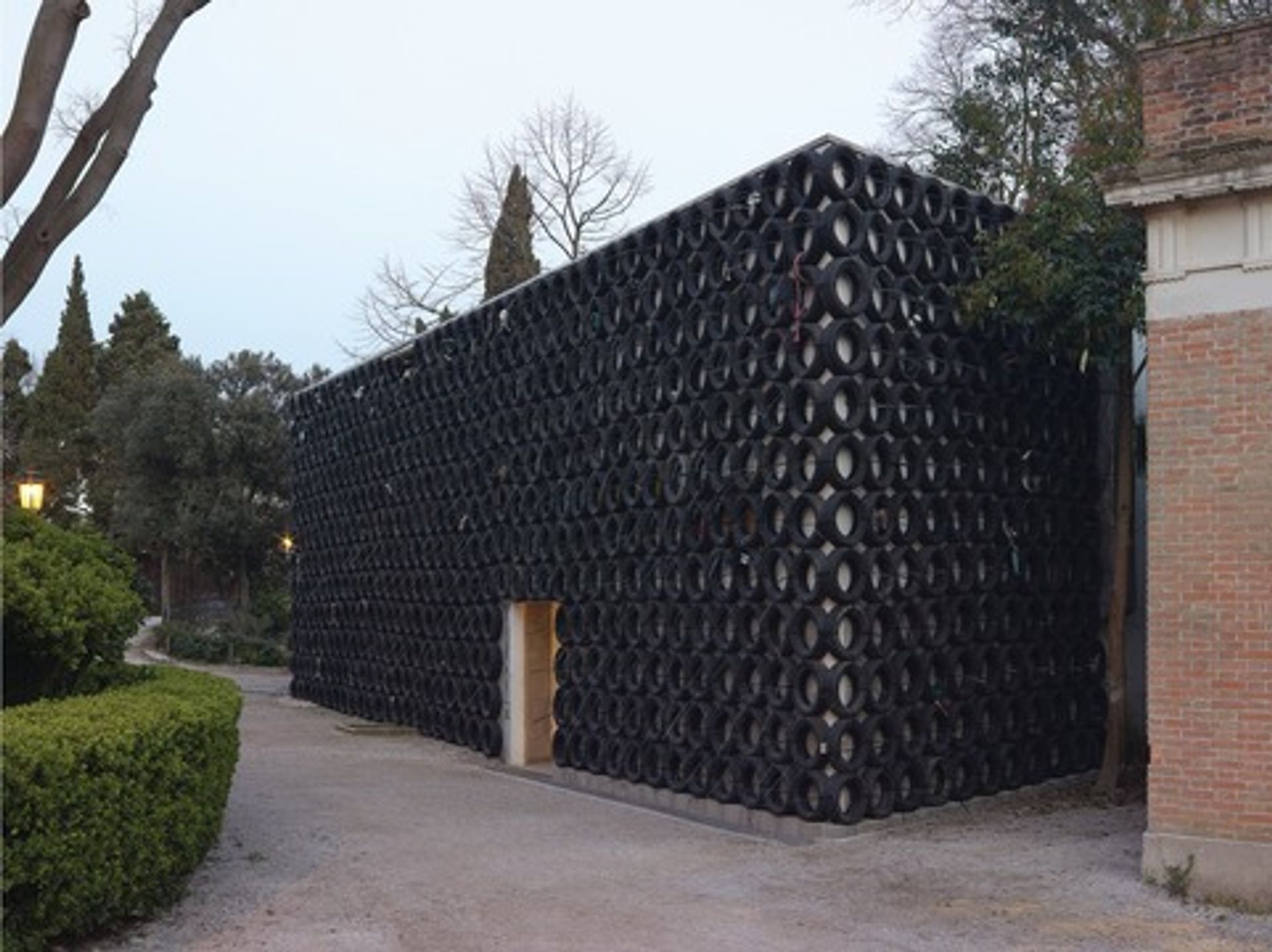

Archaeology of the Present, Israeli pavilion Tsibi Geva

The Tel Aviv-based artist Tsibi Geva’s installation in the Israeli pavilion, entitled “Archaeology of the Present”, will be nothing if not unsettling. The pavilion’s exterior (above) is enveloped by 1,000 used black tyres, tied together to create a grid “that forms a protective layer of sorts over the pavilion”, according to the curator Hadas Maor. This “delivers a sense of existential anxiety and urgency”, she says. Inside are “undefined, intermediate spaces”, filled with reclaimed objects such as doors, windows and shutters, which bring to mind a typical Israeli boidem, or attic. Among the clutter are sculptural installations and paintings. The surrounding detritus reflects a “state of consciousness… shaped by an aesthetic of uprooting and immigration”, Maor says. But she argues that Geva’s politics are implicit rather than explicit. “His work is pervaded by the impossible complexity of Israeli-Palestinian existence, and is imbued with a painful, sober and harsh awareness,” she says.

Armenity, Armenian pavilion 18 artists including Hrair Sarkissian and Aram Jibilian

The Armenian government is using the Biennale to mark 100 years since the killing of up to 1.5 million Armenians by Ottoman Turks during the First World War. (The Turkish government disputes Armenian claims of genocide.) Notably, the 18 participating artists from the Armenian diaspora include Zabunyan Sarkis, who is also in the Turkish Pavilion. Adelina Cüberyan von Fürstenberg, the organiser of the show on the San Lazzaro degli Armeni island, says that, despite the events of 1915, “Armenian culture has remained alive, making its artists genuine global citizens”. They include New Yorker Aram Jibilian (above, Gorky: a Life in 3 Acts (i.Birth), 2008) and Damascus-born Hrair Sarkissian (main image, Unexposed, 2012), whose subject is the descendants of Armenians who survived by converting to Islam. “Having… reconverted to Christianity, [they] are forced to conceal their newfound Armenian-ness,” he says.

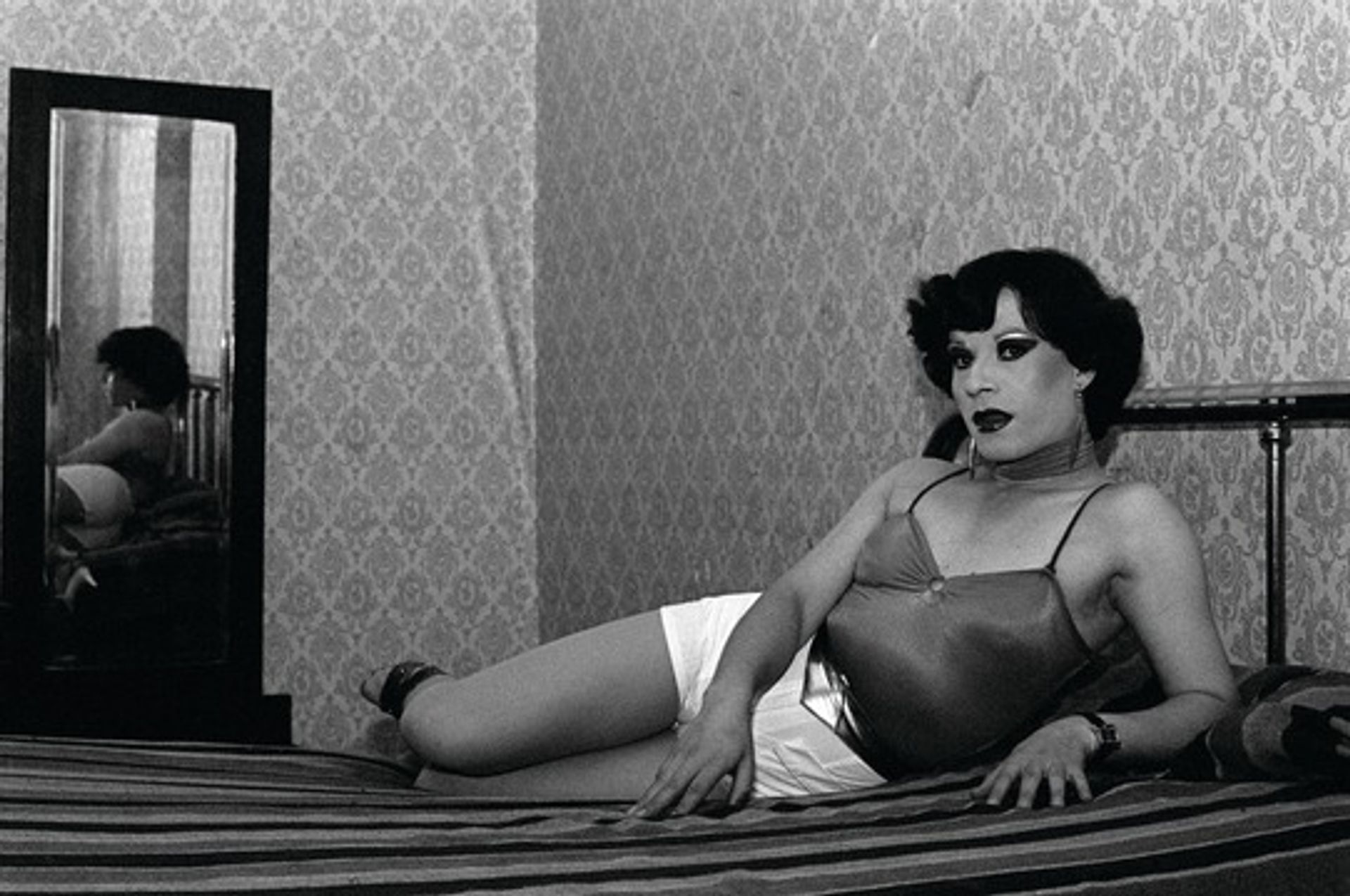

Poetics of Dissent, Chilean pavilion Lotty Rosenfeld and Paz Errázuriz

Photographs of male transvestites in Santiago brothels are an unlikely mirror of Chile in the 1980s, but Paz Errázuriz’s series “La Manzana de Adán” (Adam’s apple), 1982-87, portrays repressed communities under Augusto Pinochet’s dictatorship. The series, including Evelyn 1, 1982 (below), reflects “one of the most fearsome… moments of Chile’s sexual and political history”, according to the scholar Cecilia Brunson. Many transvestites were tortured and killed. “They were not [protected by] a union [or] defended by any human rights bodies,” Errázuriz says. The Biennale is showing a new edition of the series with “mostly unpublished colour photographs”, she says, shown with works by the artist Lotty Rosenfeld. Errázuriz says that there is still “much to repair” in Chile. “Forgetfulness overwhelms many groups that have not been heard in their entirety, and we have much to fight for so that these voices are addressed.”