Before it even opens to the public this weekend, the Whitney Museum’s new home in the Meatpacking District has been marked as a success. Critics who usually never agree on anything have been nearly unanimous in their praise of the Renzo Piano-designed building and the inaugural exhibition presenting a potted history of American art. And this Thursday, the museum received an official seal of approval when First Lady Michelle Obama attended the dedication ceremony and said that after "too brief a tour… I fell in love with the building", calling the Richard Artschwager-decorated lifts from the main lobby, "the most beautiful freight elevators I've ever ridden on".

Just a week before VIPs were allowed in to sneak a peek at the new museum, while the last bolts were tightened and the final touches made on the installation of the collection, the Whitney’s director Adam Weinberg took us on a personal tour. As we walked through the museum, the ever-engaged Weinberg stopped to check in with colleagues and construction staff, from the curator overseeing artist projects to the head chefs.

One of the first such run-ins is with the artist Mary Heilmann, who came to the museum to oversee the installation of Sunset (2015), two large geometric panels that adorn the building’s exterior wall, and a scattering of candy coloured chairs on the terrace that doubles as an outdoor gallery. “It’s so joyous,” Weinberg told Heilmann of her project.

Another artist installation, on long-term loan from Lawrence Weiner, is a cast-iron manhole cover original commissioned as a project by the Public Art Fund anchored on the Whitney’s front steps. And impossible to ignore is Felix Gonzalez-Torres’s string of lightbulbs that cascades down the central stairwell.

Such site-specific installations are due to be the norm at the new Whitney. “We wanted to let artists see all of the museum as a space for opportunity,” Weinberg said, adding that he expects artists to come up with more ideas for inventive installations on the terraces. For now, the outdoor spaces serve as a kind of extension of the galleries, the angular forms of Robert Morris’s steel sculptures on the terrace complementing the works by Donald Judd and Sol LeWitt on the sixth floor, for example.

“The experience of getting to the art is part of the art experience,” Weinberg said, and he stressed the importance of allowing for breaks, a consideration that will probably prove necessary as visitors take in the 600-work inaugural exhibition America Is Hard to See. “When you go to a museum, you should be able to take a moment to see the art, you should have a chance to pause. It’s not about getting on a conveyor belt and saying ‘I saw it’.” We took our own welcome moments of respite during the tour—on the fire-escape-like outdoor stairs as we admire the New York skyline, on Scott Burton's granite seating and of course on Heilmann’s cheerful deck chairs overlooking the High Line.

The new Whitney also lends itself to more performative art—a lesson learned from the 2012 Whitney Biennial, where dance was a major component, despite the fact that the Breuer building didn’t have a theatre or performance space. “We had to build a floor on top of the floor,” Weinberg said, to protect the dancers’ feet. Meanwhile, the Piano building has a “fully loaded” projection room, a theatre with wall-length windows looking onto the city, and sprung wood floors in all the galleries, “so you can have dancing throughout the museum”.

American diversity For the opening exhibition, a survey of American art drawn entirely from the collection, the curatorial team have pointedly included artists that may have been overlooked in the past, especially women, African American and Latino artists. This is not about political correctness, Weinberg said, but about “showing a more accurate picture of the diversity of American culture”.

So visitors to the new Whitney will see many names they might not know, shown alongside more recognisable artists. For example, in a gallery on the eighth floor focusing on the Industrial age, Weinberg pointed to a dynamic work by I. Rice Pereira, a “major artist of the 1930s who is lesser known now”, as well as a work by Elsie Driggs, who worked at the same time as Charles Sheeler, “both with this macho subject matter”. On the sixth-floor gallery filled with Minimalists, a wall piece by Michelle Stuart, made by rubbing graphite on paper that was laid against a cliff-side, sits comfortably next to a lead, antimony and steel installation by Richard Serra.

The show not only allowed the curators to pull key works out of storage—such as a riotous painting by E.E. Cummings (better known as a poet) that is about the translation of sound into colour—but also led them to make discoveries about the museum’s own collection. Weinberg was happy to be surprised by one such find, a collage by Sam Middleton that he said is “one of my favourites, and I didn’t even know we had it”.

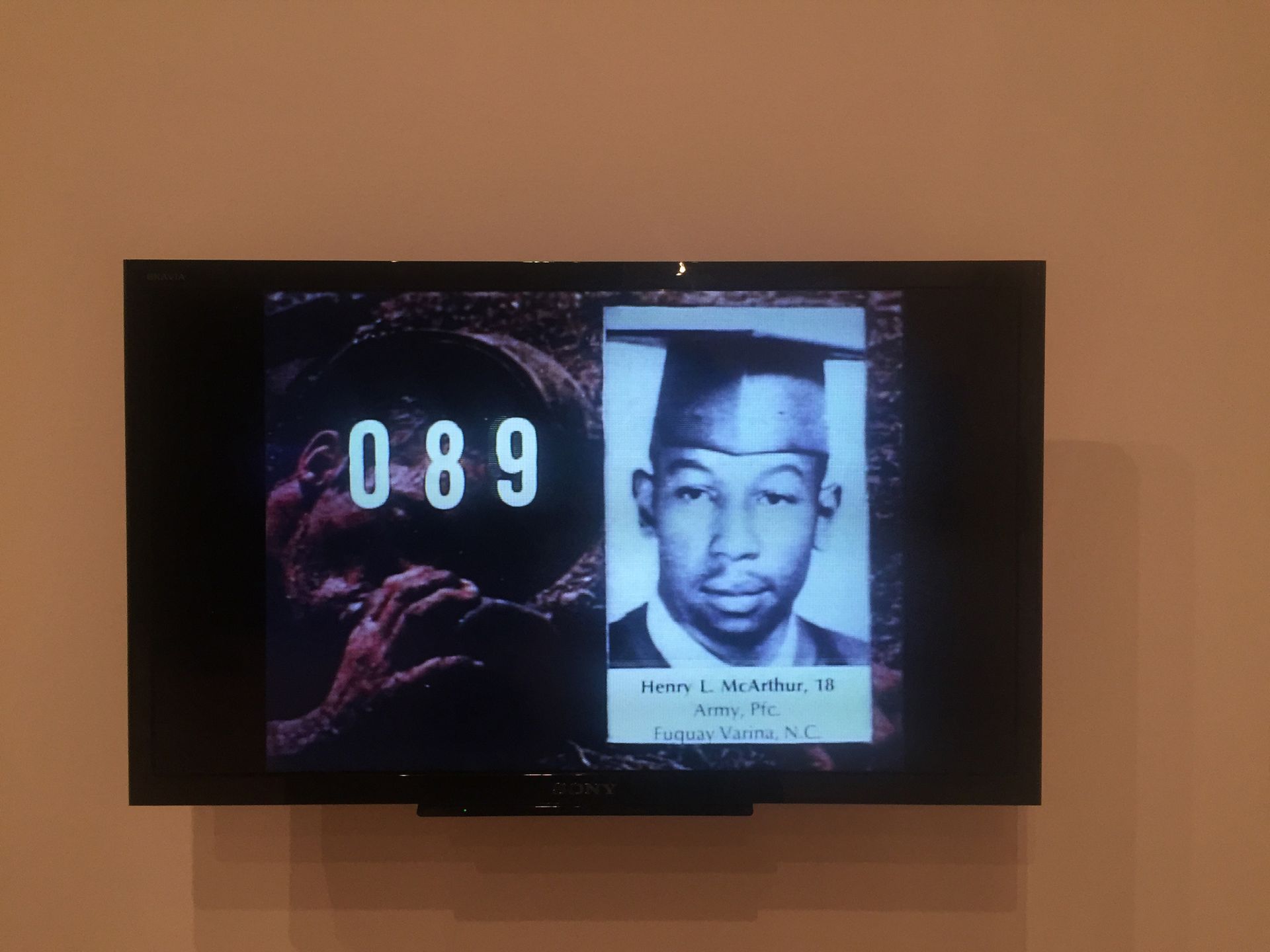

The selection does not just include art that celebrates American culture, there are also works that look at the dark parts of the country’s history. There is a powerful wall of works on paper dedicated to the anti-lynching movement of the 1930s on the seventh floor, while a video by Howard Lester on the sixth floor counts the number of soldiers who died in Vietman during one week. “It’s chilling,” Weinberg said, as we watch young men’s faces flick past to the tune of Bye Bye Love.