As the bloody civil war in Syria enters its fifth year, a few brave artists are continuing to make and display work in the country, despite the worsening security situation. “The more war they do, the more art we will do,” says the Syrian-Armenian photographer Issa Touma.

Although many of the country’s most notable artists have fled, Touma, who has struggled to keep Aleppo’s sole surviving gallery alive, defiantly staged the 12th annual Aleppo Photography Festival in January. The event’s previous space, a former church, is occupied by Islamist fighters, so he projected around 100 works by Arab and Western artists on his gallery’s walls for a week. “Our festival gives the chance for Aleppians to stop in front of international art like any other citizen around the world; to feel normal for one day,” he told The Art Newspaper in a Skype interview. Around 500 people attended the exhibition, he said. Touma, who was trapped in his home for nine days in 2012 when the front line reached his street, reported a “bloody week” when we spoke to him. A bomb hit a street near Touma’s home, killing several people.

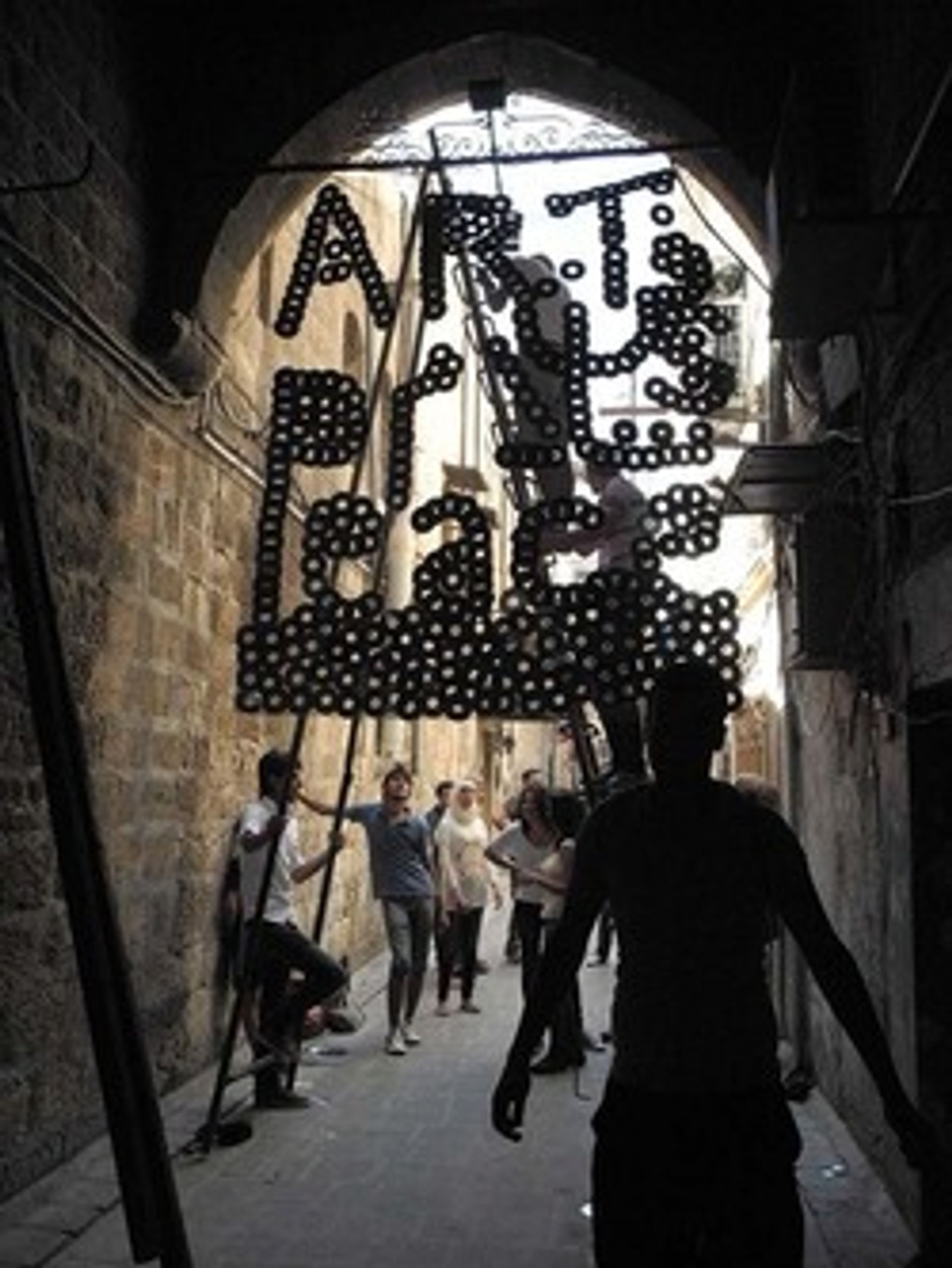

Campaigners raise an "art is peace" sign in Aleppo as part of the Art Camping movement, founded by the gallerist Issa Touma. He also co-ordinates the Aleppo Photography Festival, which went ahead in January

Visa rules tightened up

The veteran artist Youssef Abdelke, whose work is in the collection of the British Museum in London, has also refused to leave the country, despite being detained in 2013 after signing a declaration calling for President Bashar Assad to step down. Another artist who signed the declaration reportedly fled Syria after his brother was detained. “It depends whose list you are on and who is paying attention. They cast a wide net,” says one artist and curator in the UK who asked not to be named. “Artists have to be careful about what they are doing, and they can’t comment too closely,” another gallerist says.

Deciding whether to stay in Syria is far from easy. Extremists who film beheadings “are not only against art, they are against life itself, and everything that comes with it”, says the leading artist Thaier Helal, who is based in the Gulf state of Sharjah and whose work was recently shown in London.

For those artists trying to leave, migrating to nearby countries in the Middle East is getting more difficult, says the Paris-based curator Delphine Leccas. Lebanon has new requirements for visas and residencies for Syrians, Egypt’s government is no longer sympathetic and Jordan requires them to declare refugee status. “Now that it seems the conflict is not going to end any time soon, the situation is getting so precarious in Arabic countries that artists prefer to travel to Europe to settle and begin a new life,” she says. But this is also far from easy.

Many countries in Europe have made it increasingly difficult for artists to be granted even temporary visas. The same is true of the US. In January, Thaier Helal was denied a British visa to attend the opening of an exhibition of his work at the Ayyam Gallery in London, although this was later granted. Last year, Touma was denied entry to Britain, despite receiving support from Stephen Deuchar, the director of the Art Fund. Mohannad Orabi, recently named as one of the 100 leading global thinkers by Foreign Policy magazine, was barred from travelling to the US for the ceremony.

Collecting “uprising art”

Despite the difficulties faced by Syria’s artists, or perhaps because of them, their art is in the international spotlight like never before. The British Museum is adding many works from Syria to its collection as part of its efforts to collect a cross-section of “uprising art”. “The images are very powerful. Some are utterly beautiful as well as telling a dramatic story,” says Venetia Porter, the assistant keeper of the Middle East department at the museum.

Others are keen to keep the focus on the art itself, rather than its political messages. This month, the Jalanbo Collection, a leading private Middle Eastern collection founded in 1984 by an expatriate British-Syrian couple, will collaborate with the Armory Show in New York to stage tours for VIP collectors. A spokesman for the collection says that it aims to avoid a “lost era” between past and future generations in the country’s cultural history by preserving and providing access to Syrian art.

Originally appeared in The Art Newspaper as 'The plight of Syria’s artists'