The Comando Carabinieri per la Tutela del Patrimonio Culturale—the specialist cultural heritage unit of the Italian military police—presented a staggering number of antiquities in Rome on 21 January. Valued at €50m by the police, it was hailed as “the greatest recovery of art objects” in the history of the police force. The display concluded “Operazione Teseo” (Operation Theseus), a 14-year investigation into a trafficking network allegedly run by the Basel-based Sicilian dealer Gianfranco Becchina. More than 5,000 ancient objects excavated illegally from sites in Apulia, Sicily, Sardinia and Calabria—including Greek pottery, votive statues, frescoes and bronze armour—were seized from five warehouses and restituted to Italy, in collaboration with the Swiss authorities. The enquiry revealed the elaborate system by which artefacts were excavated by “tombaroli”, or tomb robbers, in southern Italy, received and restored in Switzerland and, with false documents of provenance, sold through middlemen to collectors, dealers and museums.

The Italian Supreme Court of Cassation upheld an order to return the seized loot to Italy in 2012, but the criminal charges against Becchina have expired under a ten-year statute of limitations. Aside from vague plans announced by the Italian culture minister, Dario Franceschini, to distribute the artefacts among regional museums, the future of the hoard is uncertain.

The Art Newspaper consulted antiquities specialists to assess the value of the recovered items. We asked them to identify pieces that, for their rarity or exceptional quality, are museum-worthy and others that are more common or are already represented in archaeological museums. It is important to note there is no precise historical detail about any of the items, as all were dug up illicitly. The estimates, which are based on prices for similar objects with a secure, legal ownership history, place the figure for the 5,000-strong total nearer €15m.

Rather than put more pressure on its underfunded and overstretched institutions to catalogue and store these orphan objects, we suggest the Italian government sell some for the benefit of its archaeological service.

*

Classification: Rare or routine find?

Corinthian amphora of Greek hero Theseus, sixth century BC

OUTSTANDING

This amphora depicting the Greek hero Theseus was described (probably incorrectly) by the carabinieri as “the most precious” single item in the hoard. It dates back to the sixth century BC and has been described as Corinthian. The city-state of Corinth invented the black-figure technique in around 700BC and dominated the pottery-export trade until the mid sixth century. Artists painted figures—mostly animals and occasionally mythological scenes—with a slip that turned black during firing, then used a sharp instrument to incise details such as hair and muscles. The representation of Theseus, the founder-king of Athens and slayer of the Minotaur, is rare for this period. This piece is believed to have come from an Etruscan burial site. The Etruscans, the people of what is now central Italy, imported and produced their own imitations of Greek Corinthian pottery.

Est: £30,000–£40,000

*

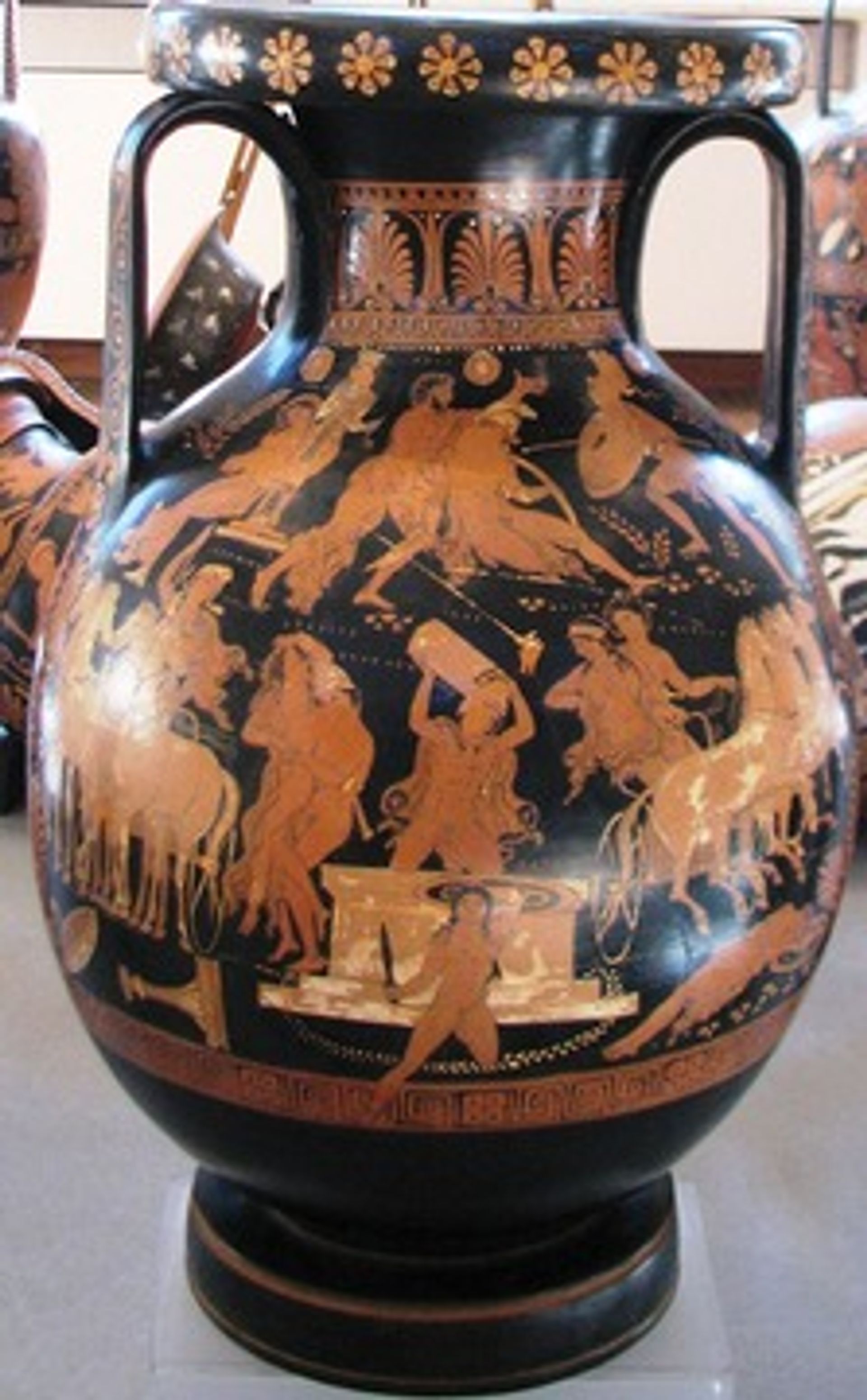

Mythological red-figure pottery

OUTSTANDING

Red-figure pottery was invented in Athens in around 530BC and gradually replaced the black-figure style. It is the inverse of the earlier technique, as the figures are left unpainted in the reddish colour of the original clay. Painting the details in black, rather than incising them, allowed for finer details and more naturalistic representations of the human figure. This elaborate mythological scene features frontal poses and three-quarter views, as well as overlapping figures. The leg of the figure with the dagger dramatically overlays the decorative pattern at the foot.

Est: £60,000–£80,000

*

Red-figure calyx krater

OUTSTANDING

Kraters were large vessels used for mixing water and wine at banquets and could also serve as funerary urns or grave markers. The calyx form, with low handles that curl upwards like the calyx of a flower, is rarer than others. The earliest known example was produced in the sixth century by the Athenian potter and vase painter Exekias. If this red-figure krater were signed and could be attributed to a painter, it would increase its value. The decoration seems to relate to the vessel’s function: a group of bare-chested male banqueters recline with a standing woman—perhaps a servant or an entertainer. It is not known if the stand belongs to the krater.

Est: £70,000–£100,000

*

Mythological red-figure bell krater

OUTSTANDING

The bell krater, shaped like an inverted bell with upturned handles in the upper half of the body, is more common than the calyx. The latest of the four types of krater, it first appeared in the early fifth century and only in red-figure. This mythological scene features serpents and one of the female figures picked out in white, which would have been added after firing. While damage can be seen at the base and on the left-hand side, there does not seem to be any overpainting.

Est: £20,000–£30,000

*

Group of vessels likely originally from Gnathia

COMMON

Gnathia in eastern Apulia developed a vase-painting tradition during the fourth and third centuries BC characterised by the application of earthy colours, mainly white, yellow and red, on a ground of black slip. This group includes many different types of vessel, such as the kylix, a shallow, two-handled drinking vessel, the deeper skyphos cup, and the epichysis, a jug with a long neck and spout. The market for these has declined in the past 15 years, halving their value.

Est: £250–£500 each

*

Pottery with female head and female figurine

COMMON

This ornament in the shape of a female head with leaves on either side of her neck, and surmounted by a robed female figurine, could be described as a pseudo vessel since it seems to be solid. Similar examples have an aperture behind the handle. Pottery from Canosa in Apulia, produced in the fourth and third centuries BC, was painted in pastel colours over a white slip rather than glazed. Usually, as in this case, only the traces of the pigments remain.

Est: £2,000–£5,000

*

Askoi flask

COMMON

Askoi—flasks with bulging bodies, thin necks and flaring rims—were named after the wineskins they resemble. They were used for pouring liquids in small quantities such as oil, vinegar and honey. The askos is a typical form from the region of Daunia in northern Apulia. More rustic than black-figure or red-figure pottery, Daunian ware features bands of geometric and floral patterns in earthy tones, mostly in the upper part of the body.

Est: £1,000–£2,000

*

Mismatched pair of gold earrings

COMMON

These earrings would have hooked directly through the lobe. They do not form a matching pair, as can be seen from the different designs on the plaited loops, and could be sold individually. The earring on the left shows some granulation, a technique using tiny spheres of metal that reached its peak with Etruscan goldsmiths and declined between the third and second centuries BC. It seems that precious stones forming the eyes of the lion’s head designs are missing from their settings.

Est: £1,200–£1,800 (for two)