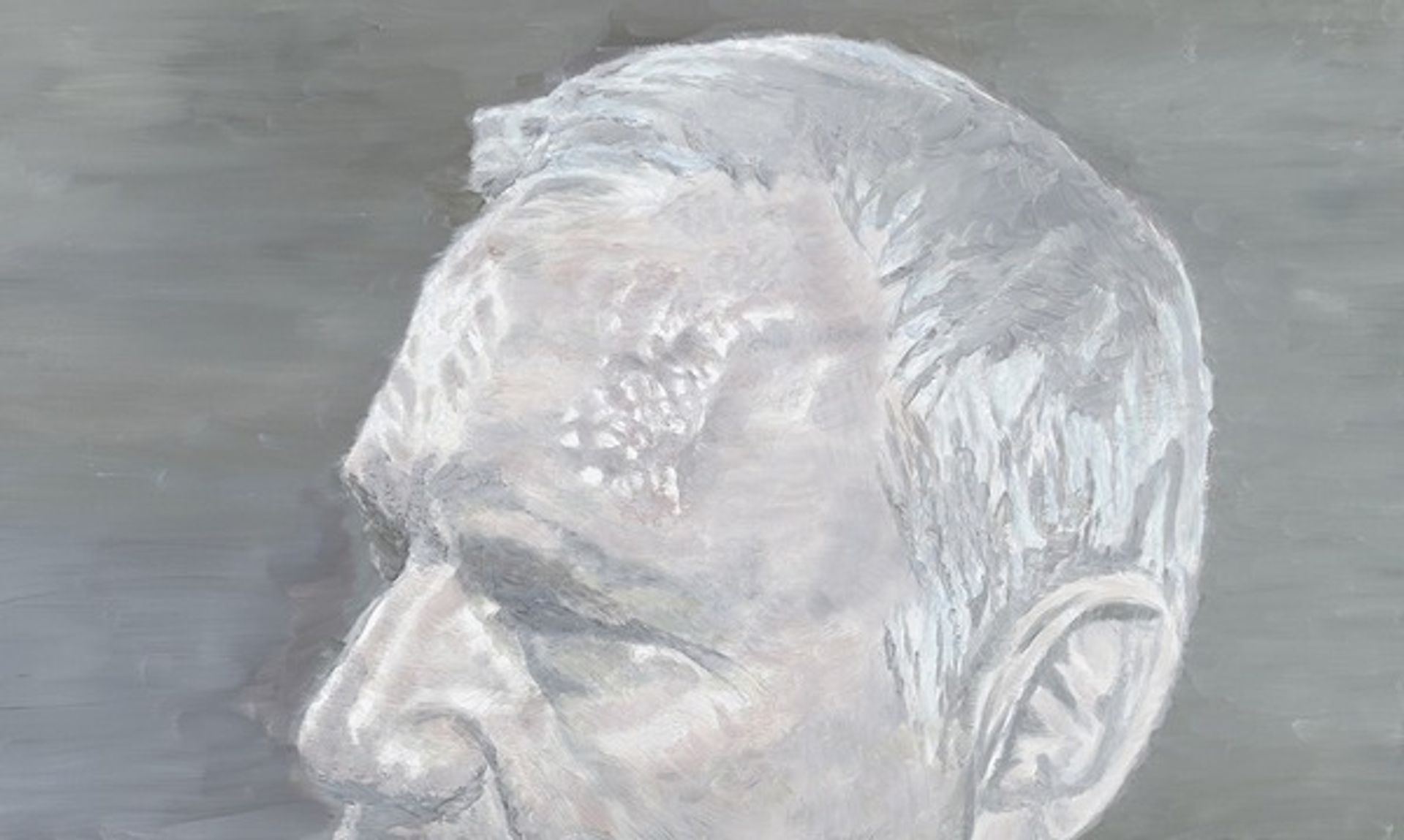

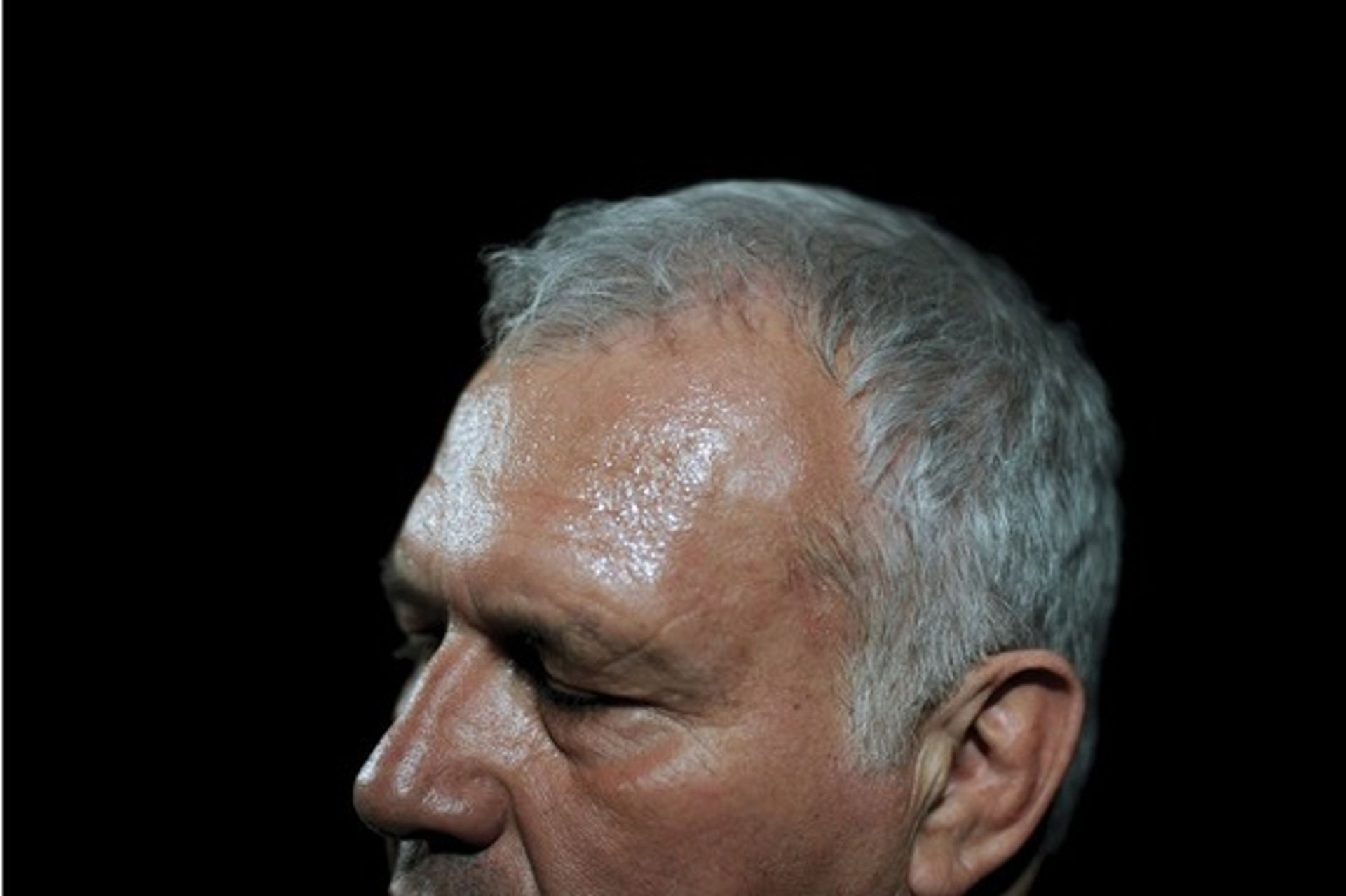

A remarkable ruling was delivered in a civil court in Antwerp, Belgium, in mid-January. It said that the Belgian painter Luc Tuymans was guilty of copyright infringement in his painting A Belgian Politician, 2011, the source for which was a photograph by Katrijn Van Giel of Jean-Marie Dedecker, the leader of the right-wing LDD party. Tuymans’ picture was heavily based on Van Giel’s portrait, using the same dramatic cropping of the face, the same letterbox format and with equal focus on Dedecker’s sweaty brow. Yet it was a clear transformation of the image from one medium into another, with all the attendant baggage that brings.

The court rejected Tuymans’s defence that it was not a copy but a parody, a ruling that delighted Van Giel’s lawyer Dieter Delarue, who said: “The court followed our argument that the work of Tuymans is not a humorous work, which is the most important requirement for a work to qualify as a parody.”

A Belgian Politician by Luc Tuymans

Jean-Marie Dedecker, the leader of the right-wing LDD party Photo: Katrijn Van Giel 2010

The subtleties of parody

But Tuymans’ three-decade career is full of works that might appear deadpan, with their muted and blanched tones, yet often sardonically question his source material. That material might be in the form of other works of art, photography, or stills from film or television, and can depict subjects as art historically loaded as a still-life, as politically potent as Belgium’s colonial presence in the Congo, or as preposterous as a sweaty politician. He never makes belly-laugh satire, but his pictures are often quietly, unsettlingly parodic.

The wider, most troubling, implication of this case is that an artist’s right to take an image and adjust its form and context, and thus its meaning, is being questioned. And it is happening with increasing frequency. In recent months, Jeff Koons has twice been accused of plagiarism in relation to sculptures, based on existing photographs, from his “Banality” series in his Centre Pompidou exhibition (until 27 April). And Richard Prince, not long after a gruelling legal saga relating to his appropriation of images by the photographer Patrick Cariou, has recently been sent a cease-and-desist letter asking that he stops displaying or disseminating works that include Donald Graham’s images; one of his recent inkjet prints featuring Instagram pages included a third party’s posting of a Graham photograph.

Forms of appropriation have been central to Modern art. The quote, “Good artists copy; great artists steal” is often attributed to Picasso, but the fact that a version of it certainly emerged from TS Eliot (“Immature poets imitate; mature poets steal”) and also reportedly from Stravinsky (“A good composer does not imitate; he steals”), indicates that aggressive appropriation has been a preoccupation of Modernist creators across the cultural spectrum.

Images as “found”

Post-Marcel Duchamp, of course, images have become another form of readymade to be used as “found”, decontextualised and revivified within art galleries, in the disparate works of Robert Rauschenberg, Richard Hamilton and Andy Warhol, in the paintings of Gerhard Richter and Marlene Dumas, and most directly in the self-conscious appropriations of the Pictures Generation, including Sherrie Levine and Richard Prince.

This conceptual approach might make appropriation more blatant, but it is not a new phenomenon; artists have been borrowing from other images forever. The forms of the Renaissance were based on the liberal copying and quotation of figures and compositions from antique sculptures and friezes, and from the works of artistic forebears and peers. And ever since, artists have stolen or paraphrased whole chunks of other artists’ works. Raphael, Titian, Rubens and Watteau, to name but a few, were all inventive borrowers. And as soon as photographs appeared in the 19th century, artists used them just as earlier artists had used engravings, paintings, casts and sculptures.

Appropriation, far from being a newfangled thing, is a venerable tradition, whether in the form of homage, quotation or, indeed, as parody, and it has consistently helped artists—Tuymans among them—push art in new directions.

*

The borrowers: artistic quotations over five centuries

16th century

Raphael, The Bridgewater Madonna

Raphael, The Bridgewater Madonna, around 1507, Scottish National Gallery, Edinburgh

Michelangelo, Taddei Tondo (The virgin and child with the infant St John)

Michelangelo, Taddei Tondo (The virgin and child with the infant St John), around 1504-05, Royal Academy of Arts, London

Michelangelo’s exquisite unfinished relief features the Christ child turning away from a goldfinch, symbol of the Passion, held by John the Baptist. The infant Jesus’s movement, twisting and stretching across the Virgin’s lap, clearly moved Raphael, who drew directly from Michelangelo’s relief in a drawing now in the Louvre. He went on to adapt it in this beautiful ‘Mother and Child’, which in its gentle mood owes a great deal to Leonardo. Crucially, Raphael adjusts the heads of Mary and Jesus so that the wriggling child meets his mother’s tender gaze.

*

17th century

Adam Elsheimer, Judith Slaying Holofernes

Adam Elsheimer, Judith Slaying Holofernes, 1601-03, Apsley House, London

Cornelius Galle der Ältere after Rubens, Judith Beheading Holofernes

Cornelius Galle der Ältere after Rubens, Judith Beheading Holofernes, 1610-1620, Bibliothèque Nationale de France

Sadly, the Rubens painting is now lost, but this is a particularly interesting pairing because Rubens owned the Elsheimer and freely adapted his composition from it, most notably Elsheimer’s dramatic innovation of Holofernes’s raised leg. It’s a classic example of Rubens’s embellishment of his sources; many of the fundamental elements remain the same but Rubens pours a whirlwind of energetic movement and rich detail into the painting, transforming Elsheimer’s example.

*

18th century

Joshua Reynolds, Lady Cockburn and her Three Eldest Sons

Joshua Reynolds, Lady Cockburn and her Three Eldest Sons, 1773, The National Gallery, London

Anthony Van Dyck, Charity

Anthony Van Dyck, Charity, around 1627-28, The National Gallery, London

Reynolds often based his compositions on the Old Masters and this is one of the most striking examples because it borrows from two. It draws heavily on Van Dyck’s painting in capturing the female protagonist with three infants, but it also lifts the left-hand child from Velázquez’s Rokeby Venus, 1647-51, another National Gallery picture. The connection of Lady Cockburn with the virtue of charity is no accident, of course, but when the painting was made into an engraving, it was named after the Roman matron Cornelia, a classical reference appropriate to Reynolds’s antiquity-obsessed epoch.

*

19th century

Edgar Degas, Princess Pauline de Metternich

Edgar Degas, Princess Pauline de Metternich, around 1865, The National Gallery, London

One of the very first major paintings to be based on a photograph. Degas took the image from a visiting card given out by Princess Pauline and her husband, the Austro-Hungarian ambassador in Paris; he removed the ambassador from the image. Most strikingly, Degas makes no secret of his photographic source—hence the blurring in the Princess’s face and the entirely unnatural colour of the painting. It is a genuinely revolutionary painting, prefiguring numerous key 20th- and 21st-century artists’ work, from Francis Bacon to Andy Warhol, Gerhard Richter to Luc Tuymans.

*

20th century

Walter Richard Sickert, A Conversation Piece at Aintree: King George V and his Racing Manager

Walter Richard Sickert, A Conversation Piece at Aintree: King George V and his Racing Manager, around 1927-30, Royal Collection, Clarence House, London

Few artists have used found photography as powerfully as Sickert. This image was based, like many of Sickert’s paintings after the 1920s, on a news photograph of the king at the Liverpool racecourse. Sickert would square up his photo-based paintings using a grid which is often visible amid the brushwork. Though this painting is small, Sickert would often use the grids to create works on a monumental scale, as in another royal portrait based on a photograph, his H.M. King Edward VIII, 1936, a nearly 2m-tall picture, in which he captures the controversial monarch stepping out of his car.

*

Beyond the visual arts: quotations, pastiches and borrowings in literature and music

Music

● Variations on themes by living composers are often named on the title page of works: Mozart’s work features variations on Johann Christian Fischer, Giovanni Paisiello, Antonio Salieri and many more.

● In the final act of Mozart’s opera, Don Giovanni listens to his private band playing popular melodies by living composers Vicente Soler and Giuseppe Sarti as well as, famously, Mozart’s own “Non più andrai” from “The Marriage of Figaro”.

● Quotations can send up the original: Debussy’s “Golliwog’s Cake Walk” from his piano suite “Children’s Corner” spoof-quotes the opening bars of Wagner’s “Tristan und Isolde”. Emmanuel Chabrier’s “Souvenirs de Munich” and Gabriel Fauré and André Messager’s “Souvenirs de Bayreuth” are also based on Wagner themes.

● William Walton used two of Joseph Canteloube’s “Chants d’Auvergne” in his soundtrack for Laurence Olivier’s “Henry V”, claiming that they were folk tunes. Walton was sued for copyright infringement.

Desmond Shawe-Taylor, surveyor of the Queen’s Pictures

Literature

● Scholars have pointed out the very high degree of verbal correspondence between passages in John Florio’s 1603 translation of “Of Cannibals” from Montaigne’s Essays and in Shakespeare’s “The Tempest”.

● Goethe said that Stendhal “knows well how to appropriate foreign works” when he discovered the Frenchman had lifted passages from Italian Journey (1816) for Rome, Naples and Florence (1826).

● The structure, vocabulary and many phrases of Father Arnall’s “Hell sermons” in James Joyce’s A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man come directly from the Jesuit Giovanni Pietro Pinamonti’s Hell Opened to Christians, to Caution them from Entering into It (1688).

● In 2006 Ian McEwan denied that he had plagiarised sections of a 1977 memoir by Lucilla Andrews for his 2001 novel Atonement. He acknowledged his debt to her, but said he had not copied her work.

Originally appeared in The Art Newspaper as 'The verdict that flies in the face of art history'