After reading an article in The Art Newspaper, a collector discovered that a Rothko painting he bought for $7.2m in 2008 was one of the dozens of forged works sold by Knoedler gallery in New York. He is now suing former employees of the gallery, which closed in 2011, as well as a respected curator who, the collector says, staked his reputation on the work’s authenticity.

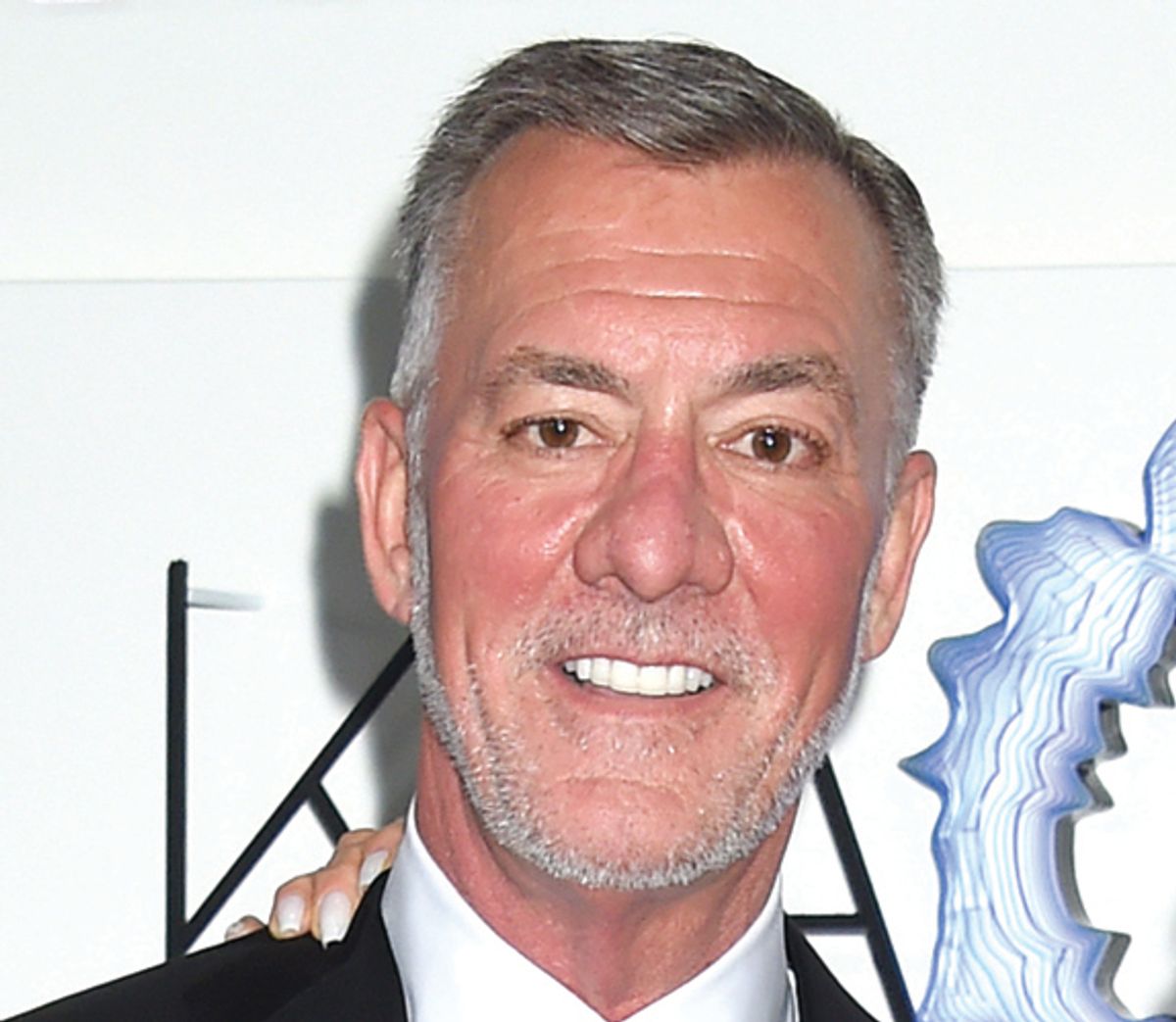

The Las Vegas casino owner Frank Fertitta and the private dealership Eykyn Maclean are accusing Oliver Wick, formerly a curator at the Fondation Beyeler in Basel, of misleading them about the fake painting. In an email to the dealership in April 2008, Wick—who acted as an agent in the sale of the forged work—detailed a provenance for the painting and wrote: “I confirm that this work has been submitted to the [Rothko catalogue raisonné] team, all is perfectly fine, otherwise I would not want to be involved with it. For this I stand with my name as a Rothko scholar.”

Wick had requested that certain claims against him be dismissed from the lawsuit, but a Manhattan federal court denied his request on 29 January. He will have to give pre-trial testimony and produce documents relating to these claims, and may stand trial with other defendants, including Ann Freedman, formerly Knoedler’s director, and the Long Island-based art dealer Glafira Rosales, who pleaded guilty to money-laundering and tax evasion in 2013 and admitted that she had brought around 30 fakes to the gallery, including the fake Rothko that Fertitta bought. The Swiss lawyer Urs Kraft is also named as a defendant, accused of acting as Wick’s agent when he “warranted” that “the painting is authentic” in its bill of sale.

Legal dispute

According to court papers, the gallery wanted to remain anonymous in the sale of the work, so worked with Wick to sell it. He offered the forged Rothko to Eykyn Maclean, which contacted Fertitta. After Wick’s 2008 email, Fertitta bought the painting for $7.2m.

Fertitta resold the work in March 2011, but reimbursed the buyer $8.5m after reading an article in The Art Newspaper in 2013 that revealed who had bought the Knoedler forgeries. At this point, Fertitta realised the work was fake.

Wick and Kraft asked the court to dismiss breach-of-warranty claims filed against them because the plaintiffs sued after the four-year statute of limitations expired (the lawsuit was filed six years after the sale). Breach-of-warranty claims are typically straightforward to prove. “If you say it’s a Pollock and it’s not, you can show a breach of warranty,” says the lawyer Dean Nicyper of Withers Worldwide, who is not involved in the case.

District Judge Paul Oetken granted Kraft’s motion to dismiss the warranty claim but denied Wick’s. This was because, after the original sale, Wick tried to sell another alleged Rothko to Fertitta, the plaintiffs contend, saying that it was a “perfect match” and looked like it had been painted “within a week” of the other work. The judge ruled that these statements could have misled the plaintiffs into believing that the first Rothko was authentic, and so kept them from suing earlier.

Wick and Kraft are also accused of fraud, which is more difficult to prove because the intent to defraud must be evident. Both have said that they believed the paintings were authentic.

Whose opinions are protected?

The Knoedler fallout, which began in 2011, has focused attention on the risks of authentication. It has since become “general wisdom” for authenticators to have a contract with the buyer that protects them from liability, says the lawyer Dean Nicyper, who chaired the New York City Bar Association committee that drafted legislation to protect independent authenticators. It was introduced in the New York State legislature last year but was not enacted. “We’re working to have it reintroduced this year,” he says. “The legislation excludes anyone with a financial interest in the transaction, so it wouldn’t apply to dealers who sold the work.” If the plaintiffs’ allegations in the Fertitta case are true, the legislation would not cover Wick because “he functioned as one of the dealers”, Nicyper says. The plaintiffs argue that Knoedler marketed the fake Rothko through Wick, and that Fertitta paid him $150,000 and the gallery paid him $300,000 for his role in the sale.

• Originally appeared in The Art Newspaper with the headline "Collector discovers Knoedler fake after reading The Art Newspaper"

Update: 2020 vision

The $80m forgery scandal that shuttered the prestigious Knoedler gallery highlighted risks inherent in the secretive art market—anonymous owners, handshake deals, uncertain provenance, experts afraid to speak for fear of being sued. The details became public through three criminal indictments, one guilty plea, and ten lawsuits against Knoedler and its ex-director Ann Freedman. The forger, Pei-Shen Qian, painted the fakes in his Queens garage. The man who recruited him, Jose Carlos Bergantiños Diaz, aged them with teabags. Bergantinos’s lover, Glafira Rosales, brought them to Freedman, claiming she got them from a mysterious Mr X. Two documentaries out this year (this reporter appears in one, Driven to Abstraction) attest to the scandal’s continuing fascination. Rosales pleaded guilty and received a lenient sentence. Bergantiños and his brother, both indicted, defeated attempts to extradite them from Spain. Qian fled to his native China. All the lawsuits settled. Though Knoedler imploded, Freedman now runs her own gallery on Manhattan’s Upper East Side. — Laura Gilbert, US legal correspondent, The Art Newspaper