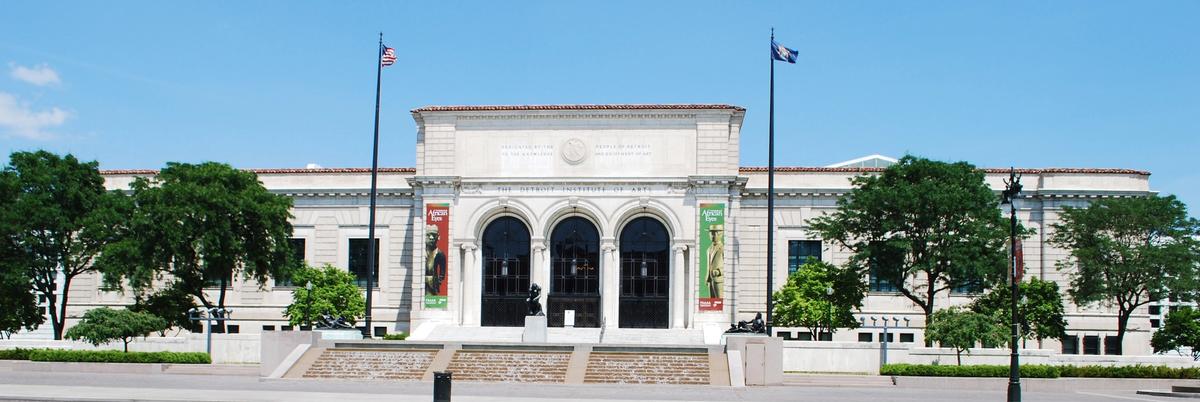

It’s there carved in stone above the entrance of the Detroit Institute of Arts (DIA): “Dedicated by the people of Detroit to the knowledge and enjoyment of art.” Not the building, of course, but the museum’s collections: thousands upon thousands of works of art acquired through the generosity of people who believed in the power of art to improve the lives of others they didn’t know and would never know. It was their gift to the future. And now, through no fault of their own, that future is being threatened.

After decades of social, economic and political failures, Detroit is bankrupt. Its emergency manager says the city’s debt is between $18bn and $20bn. Investors and pensioners are likely to have to settle for less than they were promised. But no one really knows. Municipal bankruptcy on the scale of Detroit’s is unprecedented.

Serving its community

Recently, at the request of its debtors, the city hired Christie’s to appraise the museum’s collection. Unlike most US museums, the collections of which are owned in trust by private foundations, the DIA’s collection is owned by the city. “The city must know the current value of its assets, including the city-owned collection at the DIA,” its emergency manager said. It’s all part of the restructuring process that also includes assessing the city’s parking lots and airport.

It’s hard not to be sympathetic to the city and the 700,000 who still live there (less than half the population of just 60 years ago), 80% of whom are black, those left behind as their white fellow-citizens moved to the suburbs after the riots of the 1960s, taking their tax base with them. The taxable value of the entire city is now only $8bn, less than half its indebtedness.

But this is not the museum’s fault. It has worked hard to maintain professional standards and to remain relevant in a changing environment. In 2007, after six years of renovation, for which the museum raised $158m for infrastructure upgrades, it opened newly reinstalled galleries. The goal was “to help visitors better understand the art, its cultural context and its relevance to their lives”. During the first weekend, around 57,000 visitors came to the museum—almost 1,500 every hour.

The reinstallation was not without its critics, who accused the museum of “dumbing down” its installations and limiting them to an unnuanced and utilitarian educational purpose. But that was unfair. Museums are beholden to their publics. What works in one museum may not work in another. The DIA was responding to the needs of its community and reaching out to new audiences.

At the same time, the museum continued to cut costs. In 2009, it reduced its budget by 25% and its staff by 20%. Three years later, it took its appeal for support to the residents of three neighbouring counties, who voted to accept a ten-year property tax increase in exchange for free museum admission. This will raise around $23m, keeping the museum operating and enabling it to expand its programming for older visitors and students. The museum receives no financial support from the city or state.

Having done all of this, the museum now faces the prospect of having the city sell off part of its collection. But it’s not clear that it can. The state’s attorney-general declared that, in his opinion, the art museum’s collection “is held by the City of Detroit in charitable trust for the people of Michigan, and no piece in the collection may thus be sold, conveyed or transferred to satisfy city debts or obligation”.

I am not a lawyer. And legal experts disagree as to whom is right: the city’s emergency manager and state governor or the state’s attorney-general. But I know that selling off some or all of the collection will not solve Detroit’s problems.

A question of trust

Even if it’s not technically true that the city holds the museum’s collection in trust, it is morally the case. It accepted gifts of works of art from donors who believed that they were going to serve a lasting, public purpose, and it bought others with funds provided by donors who thought similarly. Some no doubt believed that the works of art with which they were identified would forever remain in the museum’s collection. Others presumed that if they were sold, the resulting funds would be limited, as museum professional guidelines stipulate, to the purchase of other works of art. Others may have imagined that the funds could be used to support conservation and education. In any case, they all must have thought that their gifts were going to be used to enhance public access to works of art.

After all, that’s what’s carved over the entrance to the museum to which they gave works of art and acquisition funds. It does not say: “Dedicated by the people of Detroit to pay off future debts.” Selling all or part of the museum’s collection for this reason is a partial, short-term remedy at the cost of a large and lasting permanent loss.

• James Cuno is the president and chief executive of the J. Paul Getty Trust