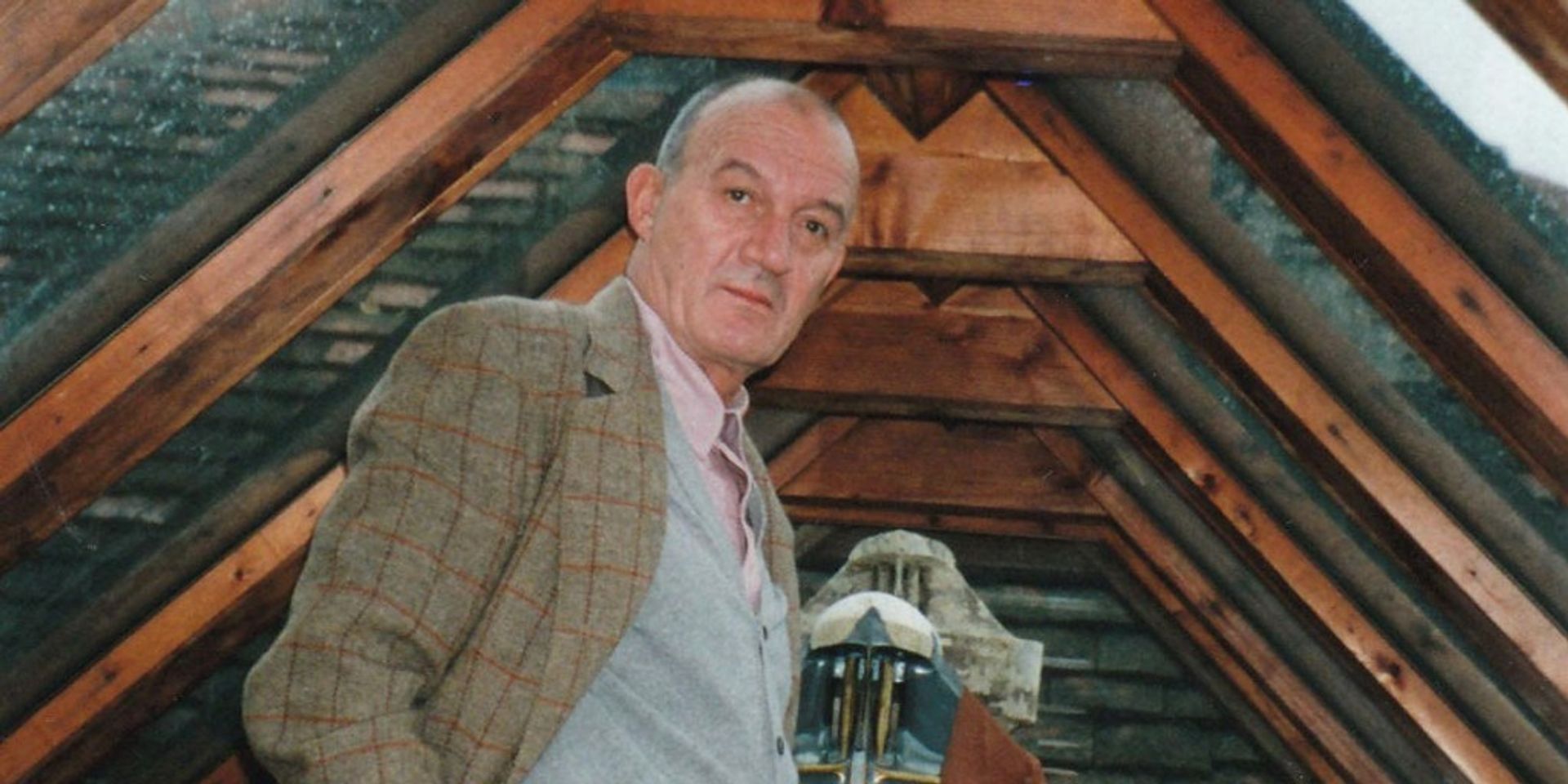

Walter Pichler in his home in Burgenland © Estate of Walter Pichler

In the easternmost corner of the Austrian countryside, in the small village of St Martin in the state of Burgenland, the Austrian artist Walter Pichler, 75, has created a world where art and architecture merge. On the land surrounding his barn, he has constructed seven life-size buildings to house his sculptural works. These “sculpture-buildings” have become a key component of his work and he rarely exhibits his sculptures without their homes.

The buildings are stylistically derived from the local architecture and blend into the surrounding landscape—the artist’s hand only becomes apparent upon entering one of the structures. The sculptures are not for sale and the artist seldom admits visitors to his farm. Indeed, when the International Council of New York’s Museum of Modern Art (MoMA)—a group of art collectors, patrons and community leaders—hoped to see the works on site, Pichler turned the offer down.

For a major retrospective which opens this month (27 September-26 February 2012) at the Museum of Applied Arts (MAK) in Vienna, however, Pichler has been persuaded to rip the sculptures from their natural environment. Organised by Pichler himself, the show focuses on works produced in St Martin, such as Torso, 1982, and Small Torso, 1993, as well as Moveable Figure, 1984, his first life-size human sculpture, complete with moveable toes. The sculpture ensemble Floating Pole, 1997, and Three Poles, 1998, marks the beginning and end of the exhibition, and refers to an ongoing architectural project consisting of a chamber submerged in the Austrian countryside, due to be completed this year. The sculptures will be accompanied by architectural models and drawings, which often serve as a blueprint for Pichler’s three-dimensional works.

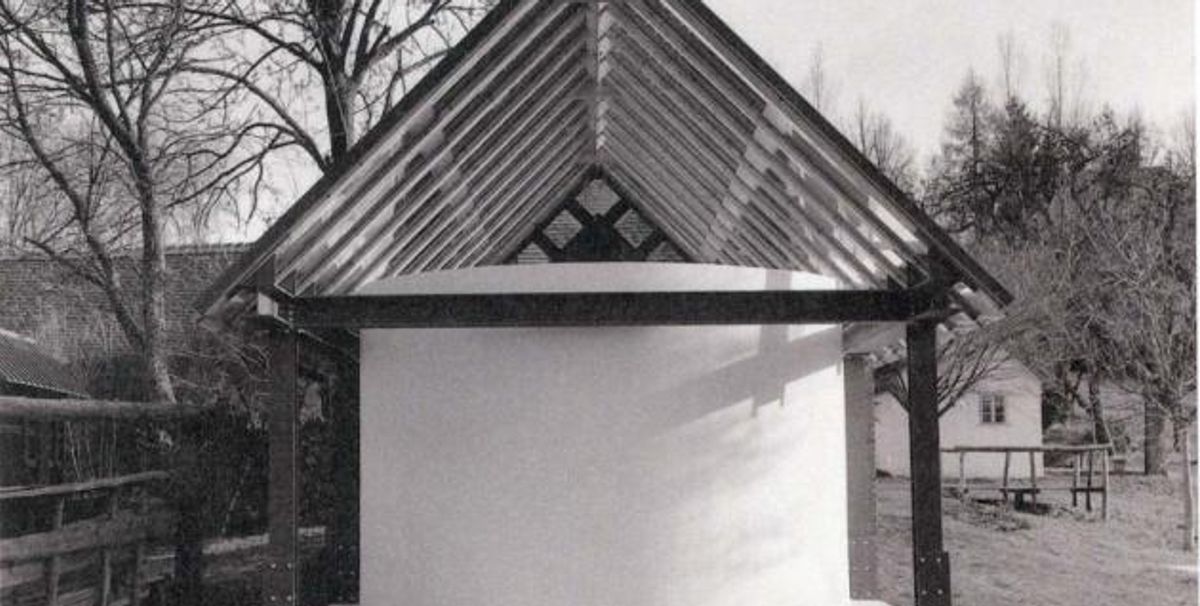

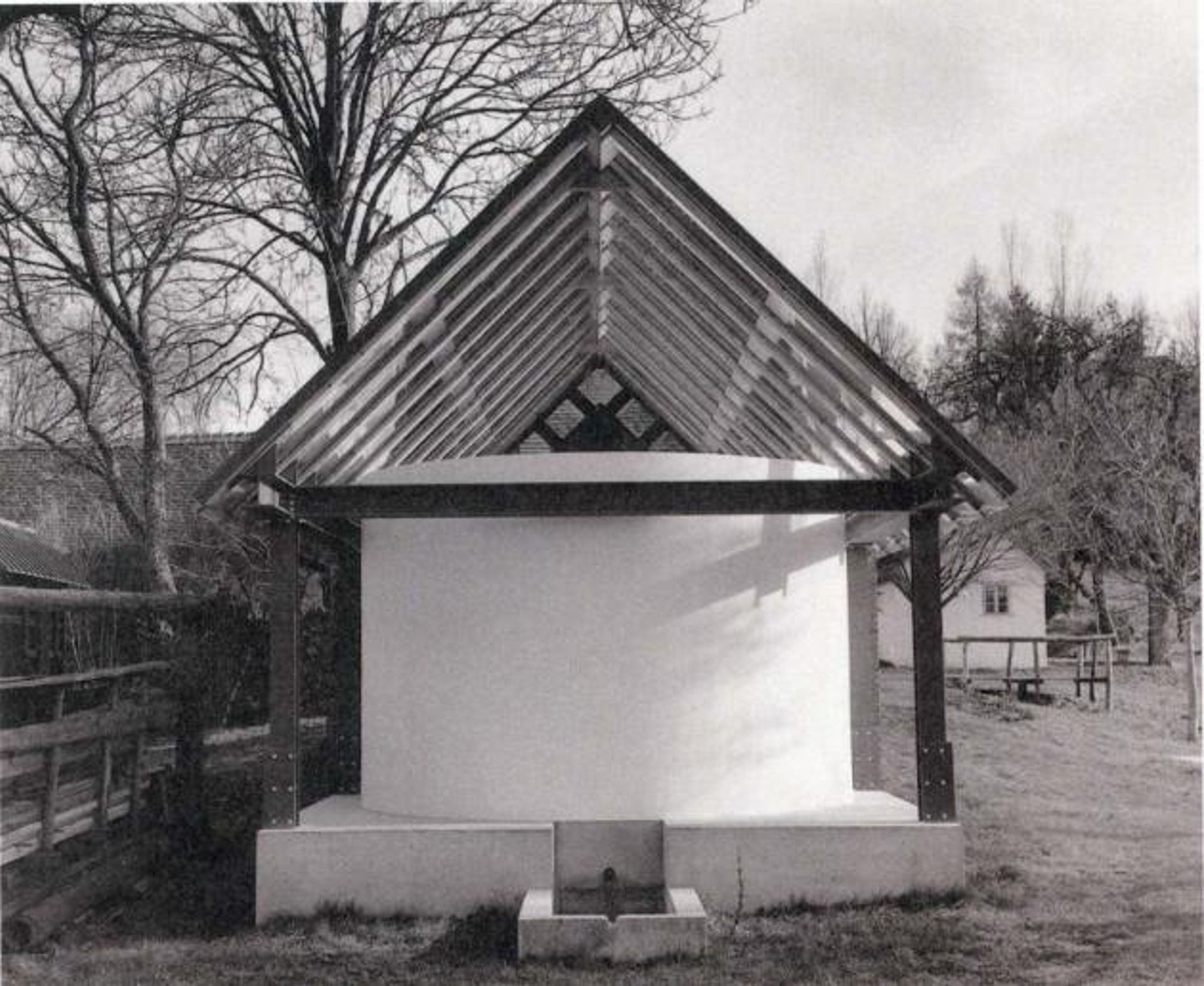

Walter Pichler's House for the Troughs, Front View, 2001 Photo: Elfi Tripamer

Born in Deutschnofen, South Tyrol, in 1936 but raised in North Tyrol, Pichler studied graphic design at the School of Applied Arts in Vienna. He was one of the early proponents of the “Visionary Architecture” movement in post-war Vienna, which was famous for its utopian drawings of buildings and cityscapes that were not meant for construction. In 1963, he published his manifesto, “Architecture”, which denounced architectural functionalism. Pichler’s work was included alongside that of Austrian architects Hans Hollein and Raimund Abraham in the 1967 show “Visionary Architecture” at MoMA.

He bought his farm in St Martin in 1972, with the proceeds of a one-off sale of a sculpture. Pichler’s move from Vienna (where he still has a flat) to the countryside was a practical one rather than an escape from the city. “I’m not some kind of country bumpkin,” he says. “The sunrise is, of course, very beautiful, but I didn’t go to St Martin because I wanted to lead some kind of sheltered existence, or because I was hoping that nature would reveal some kind of truth. I just wanted to build houses.”

Indeed, this corner of Burgenland is more artistic hub than countryside retreat. The artists Kurt Kocherscheidt, Martin Kippenberger and Christian Attersee once had homes there, and were all members of a local group called the Club at the Border, for which Pichler designed the dining room and Kippenberger the bar stools. Pichler, who began his career making architectural drawings of futuristic cities, says he “never understood how sculptors could pay so little attention to the space that surrounds their work”. He began imagining tailored environments for his sculptures. An important influence was the Romanian sculptor Constantin Brancusi, whose architectural interventions fascinated Pichler: “Brancusi used to draw exhibition spaces for his bird sculptures. For example, he wanted some to be placed in the middle of a lake, forcing the viewer to swim in order to see them. I really liked this idea, and the fact that a sculptor was getting involved with architecture.” Pichler eventually “had enough of building models”, and found the ideal conditions for realising his projects in the rural setting of St Martin.

As well as offering more space, St Martin also provided an abundance of new materials and building techniques. The metals of Pichler’s early career were supplemented by more rudimentary materials such as wood, straw, clay and bone. Pichler’s long-standing interest in vernacular architecture also attracted him to the region. Together with Raimund Abraham, the late architect of the Austrian Cultural Forum in New York, in 1963 he published “Elementary Architecture”, a photographic survey of the rural architecture in the Austrian regions of East Tyrol and Carinthia. “We weren’t exactly anonymous ourselves, but vernacular architecture was so important to us at the time because we liked the idea that great architecture could be created without an associated ‘name’. It was a way to move away from personal invention, to get away from the trend for star architects,” he says.

Basic forms of architecture were prevalent at the time; in 1964, MoMA staged “Architecture without Architects”, an exhibition of regional architecture from around the world. But while Pichler’s “building-sculptures” in St Martin can easily be mistaken for local barns or homes, they have lost their functionality and have become purely experiential. Life in the country also afforded Pichler more time—a factor that lent itself to his slow work process. He meticulously polishes and modifies his sculptures, which sometimes take several decades to complete. He says that “time flows more calmly and evenly in such an environment. It becomes a tool like clay, wood and metal. I compete with my materials over who has more patience. But I generally win in the end.” Pichler says that his early decision to stop selling his sculptures contributed to his slow pace. “I never liked the art trade,” he admits. “When I started becoming famous, a world opened up to me in which I had little interest. To be honest, I never really trusted it. My vanity didn’t extend that far; I didn’t want it. I am haughty but not vain.”

“I know my name,” he says. “I don’t need to hear it all the time. I seem to be in a different profession from Damien Hirst.”

Pichler keeps his interaction with the art market to a minimum, selling only his drawings to fund his projects in St Martin. “I am happy that my art exists on this earth and that’s all. It pleases me to create something that perhaps nobody else would be able to.” He also cherishes his freedom from an audience: “I don’t want this to become an open-air museum.” Pichler has turned down offers of financial assistance from cultural institutions and private collectors, fearing this might jeopardise his autonomy. This principle is perhaps best expressed in his self-portraits, which often show his head encased in a box. He says he is a Querkopf (square head)—an awkward customer. “I know my name,” he says. “I don’t need to hear it all the time. I seem to be in a different profession from Damien Hirst.” Nevertheless, he admits that it is “dangerous to live like this and it’s easy to become isolated”.

To stave off becoming “overly compulsive”, Pichler at times agrees to participate in exhibitions to “test” the merit of his work away from the “ideal conditions” of St Martin. The MAK, which focuses on blurring the boundaries between art, architecture and design, is an apt environment for an exhibition of Pichler’s sculptures. In fact, Pichler often says that “all my works have an intense relationship to architecture. I have always first seen my works as spaces, then as sculptures.” House for the Three Planes, 1997, for example, features three metal sculptures that can be adjusted to stand vertically or horizontally. “When the statues are horizontal and touch the building, they stop being sculptures and become part of the architecture. When they are upright, one is no longer sure whether they are art or architecture,” he says. Although most of Pichler’s “building-sculptures” stand alone, some are built as extensions to existing buildings on his farm. House for the Large Cross, 1976, his first “building-sculpture”, is an extension of a former pig stable, featuring a horizontal wooden cross supported by ledges in the building’s walls. Perched at the intersection of the two wooden beams is a copper and glass shrine. A baroque crucifix that Pichler found in his barn is buried inside the work, moulded into the metal and visible only upon opening the small shrine’s doors. Daylight seeps into the space through narrow slits in the walls, illuminating the shrine but leaving the rest of the space in relative darkness, intensifying the sacred nature of the work.

Pichler, a devout Catholic, often alludes to religion in his work, though his relationship with it often appears tense. Here, the cross is lying on its back and, in Pichler’s words, the Jesus figure is “locked away” from view. In fact, when the artist was approached by the Catholic Church to build a church on the outskirts of Vienna, he turned down the offer. “That would have been a declaration. I would have suddenly become a Catholic artist, which would have set limitations. My work mustn’t be clear,” he says.