Since the late 1960s, Lynda Benglis has been celebrated for her vibrant colour and process-oriented abstract art, which includes totemic wax paintings, poured latex floor paintings, cantilevered foam urethane sculptures, tubular knots and biomorphic mounds or spheres in bronze, lead and glass. But it was in November 1974, at the height of the feminist movement, that Benglis became famous for a racy photo she made as an advertisement for herself in Artforum magazine. It pictured her in the nude, except for a pair of white-framed sunglasses and a heavy layer of oil on her skin, and brandishing an exceptionally large double-headed dildo. Her mockery of gender politics, as well as the high-mindedness of the magazine, caused a furore that has dogged her career ever since. Spanning 40 years of work, the exhibition Lynda Benglis, includes the advert, but also corrects the balance. The show recently landed at the New Museum in New York, where it is on view until 19 June, its last stop on a five-city, four-country tour.

The Art Newspaper: Do you see this retrospective, your first solo museum exhibition in 20 years, as a kind of homecoming?

Lynda Benglis: It’s a survey, not a retrospective. It’s a sample chosen by five different curators so it’s not any one’s vision. I mean, it’s my vision, but the selection was originally made by the Irish Museum of Modern Art in Dublin, then the Van Abbemuseum in Eindhoven, then Le Consortium in Dijon and the museum at the Rhode Island School of Design wanted to do a show, so I suggested they all got together. Then the New Museum wanted me as a neighbourhood artist. I’ve had a place on the Bowery since the 1970s. Now it’s more or less a thinking room and the source of my archive.

Back then, you were spending half the year in Venice, California, and teaching at the young CalArts.

I’d been teaching at the University of Rochester, but left when Paul Brach [the first dean of the Californian school of art] invited me to CalArts. It was a perfect environment for me.

"Unsolicited opportunities are the guideposts to life"

Since that time, you have established outposts in India, Greece, New Mexico and East Hampton as well as Manhattan. How do you negotiate your work between all these places?

I’ve always liked to travel and have had studios wherever I went. I’m running 70, as they say, and I’ve spent a lot of time in all these places but I had to grow into the spaces. I didn’t build in Santa Fe until I was there for ten years. It was the same in New York. After the landlord locked me out in Venice, it made sense to buy but it didn’t make sense in Manhattan, so I moved to East Hampton. I enjoy building and I love the smell of new wood and of discovering a spot. I love waking up and not knowing where I am.

You never feel displaced?

Never. I depend on other places to give me purpose. I get a lot from nature and the culture around it. You can arrive at something you hadn’t thought of because you are in another space.

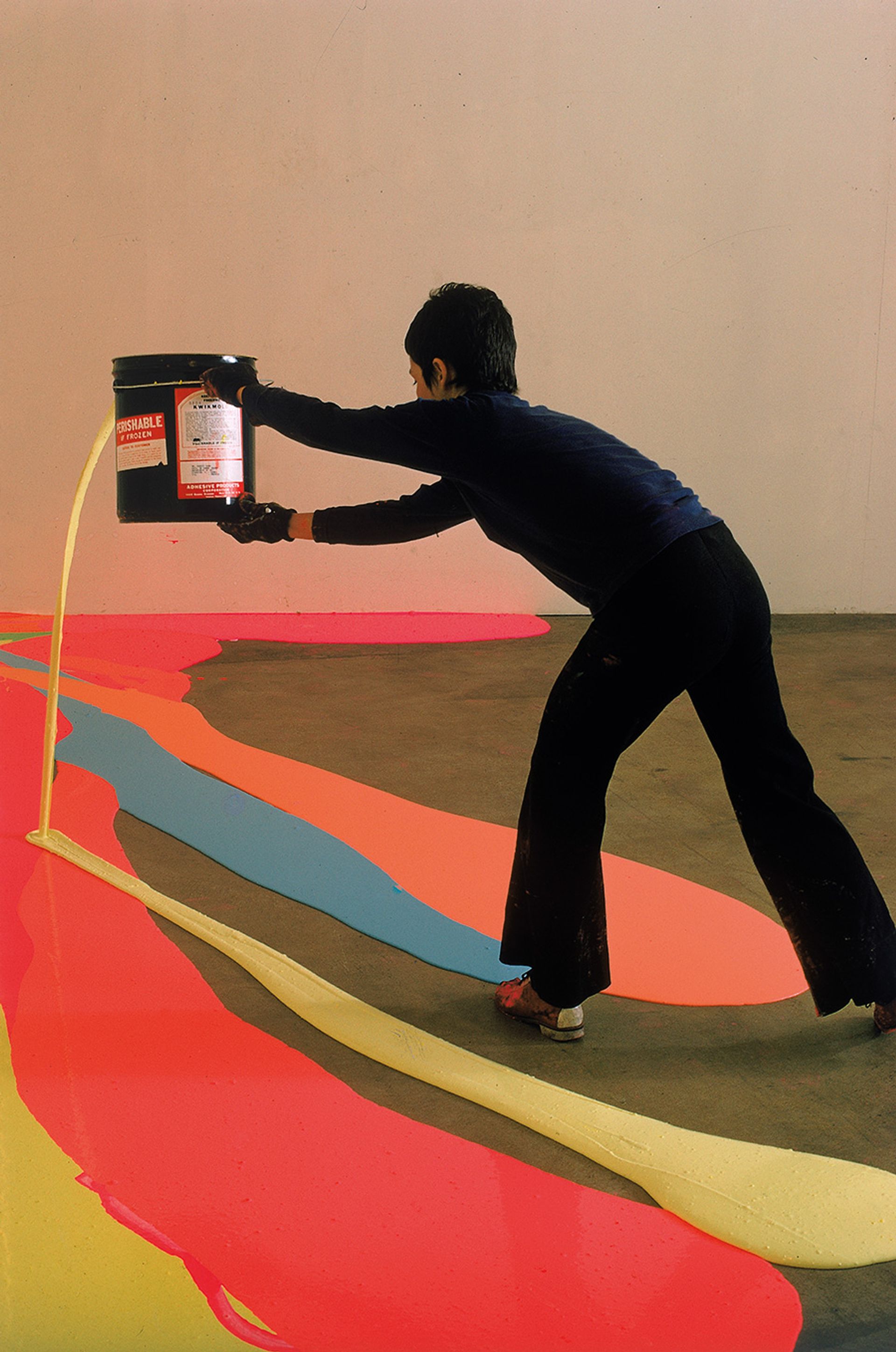

Benglis pours latex paint on the floor for Self-portrait (1970) Henry Groskinsky/Time & Life Pictures/Getty Images, courtesy Cheim & Read

How do you divide your time between one space and another?

I don’t. I’m everywhere. I just respond to the environment and my own kind of development. There’s a thread that holds it all together, because I continue to work with a type of material along the way. I’d be bored if I stayed in the same place. I also go to Walla Walla, Washington and I could have a home there too.

Because of the glassworks? There are glass pieces from the 1980s in the New Museum show.

The glass studio is in Tacoma, Washington, but I could easily buy a house there as well. In every place I try to find something to do that is interesting by asking questions of myself.

What sort of questions?

They have to do with choices presented to me. Unsolicited opportunities are the guideposts to life.

That sounds like a motto.

My sixth-grade teacher said that and I bought it hook, line and sinker. I make choices because they are there to be made. I never know where I’ll go with it.

"I make choices because they are there to be made. I never know where I’ll go with it"

What questions did you ask to get to Medusa (1999)? It looks like a bronze brain.

I started making brain-like forms after my mother suffered an aneurysm in the mid-1990s, but I had the image while scuba diving around coral reefs. A lot of my work has to do with buoyancy. I draw from everything, the trees, the bayous, the coral, whatever. Certain things attract me, I don’t know why, and then I use them. As a child I made mud mounds to sit on under the pine trees in Mississippi. Later I made more mounds, cast in bronze from polyurethane. They became semi-translucent forms that glowed from inside but they picked up light from the walls. They were like jelly. I’m interested in that illusion.

But what questions did you ask to get such results?

I started wondering: what is a continuous line? What is a sphere? How do I draw it, give it texture? I thought that texture equalled form. What is the edge of a form and how do we perceive what we see? So I’m thinking in a gestalt way. And you can see in the exhibition that I began to build on that form while thinking about how we see. My work is really not about material. I’m not a material girl! It’s about the way we see. I’ve also experimented with phosphorescence.

You’re referring to polyurethane foam works like Phantom, an environment of huge, dripping, curling, glow-in-the-dark appendages that resemble monstrous claws or lava flows that arc from the wall above the floor. This is its first exhibition since you made it at Kansas State University in 1971?

I did those pieces in five other places over a year and refused to do more because I felt I had pushed them far enough. They were all destroyed except for this one.

That’s pretty outrageous, to destroy such seminal work.

No one had money to store them then. I had no money. I had to burn my wax paintings for heat in my old studio on Baxter Street. Phantom is an artefact at this point. When you take it off the wall and put it back, it’s a part of history, and it’s something else. Art after it’s made is something else. All the in-situ works are artefacts. I won’t do them anymore. I’m not for-hire entertainment.

"I like images that challenge the viewer’s perceptions of what is or what may be and I like the image to confront the viewer, as Picasso said"

In photographs the foam pieces look both beautiful and frightening.

I like images that challenge the viewer’s perceptions of what is or what may be and I like the image to confront the viewer, as Picasso said. And I want the image to look back at you. The image exists. It’s an experience.

All of your work has distinct and aggressively sexual associations with the female body. The mounds are like sagging folds of flesh, but also dung, or pools of fluid.

I never denied the work’s feminine sensibility. I wasn’t a banner-carrying feminist but I did think they were erotic and suggested fluids. A lot of work was useful in the propaganda movement. It scared the hell out of male artists at CalArts like John Baldessari, David Salle and Eric Fischl—they were the audience. It gave them a lot of juice.

What did it give you?

I felt I was challenging myself. I was doing what I thought was necessary within an understanding of art. It’s a conversation, whether made by woman or man. I was invited to CalArts because of the feminist movement, but I didn’t go to Womenspace. I saw the work but I didn’t want to be part of this army. It opened the way for many ideas that interested both men and women, but the politics is talked about, not the visualisation.

You were in Life magazine at 30. Do you think you would be a household name by now if you were a male artist?

I never wanted to complain. I was too busy trying to think clearly about the context and was too busy having fun. I adopted an attitude of humanism. When I did the dildo work, I was interested in posing the question: What are we? Aren’t we everything—gods and goddesses? It’s a humanist issue.

"When I did the dildo work, I was interested in posing the question: What are we? Aren’t we everything—gods and goddesses? It’s a humanist issue"

Benglis’s famous 1974 advert for Artforum magazine courtesy Cheim & Read, New York

Now that you bring it up: did you buy that dildo or did you make it for the picture?

It was the largest one I could find on 42nd Street.

Where is it now?

I think it may be in my jewellery box.

You have said that you knew what you were doing when you published that photo. But how could you have gauged the reaction you actually got from both sides of the feminist divide?

I was expecting exactly that. I felt it was right for the time. And I felt it would be a challenge to my work. And it was.

It’s clearly not pornography. It pokes fun at male artist swagger and the male domination of the art market, but it’s also too funny and self-mocking to get up in your face about.

I studied pornography and thought I had to do something with it that was a work of art. I copyrighted it because I didn’t want it to be taken out of context. It’s a classic image, that’s all.

For the invitation to a show at Paula Cooper in May 1974, you did a similar nude photo but with your back to the camera and your jeans around your ankles, your head looking over your shoulder with a come-hither expression.

Just prior to the Artforum piece, Annie Leibovitz was hired by The New York Times to shoot me, so I hired her to do the jeans photo. I got her into performative photography.

You say you work from nature but your colours are not natural. The egg-shaped Chiron (2009) is an especially intense Day-Glo orange.

Day-Glo is pure colour without black. We rarely see those colours in nature but they do exist. They’re interesting mixed with other colours. I was interested in how they popped out. There’s still a kid in every person. We don’t always want to be the kid but that’s what the colour is about. It’s that memory I wish to address in the buoyancy of the work, the experience of the womb. Try diving. Go under water. You’ll feel like a baby again.

Your forms are the direct result of the actions you take to make them. There is movement contained in them.

That’s right, but I am not an Abstract Expressionist. I want that to be very clear. For me, initially, the problem with canvas was that it looked too physically there. I didn’t like the weave. I didn’t want to see it. If the process is too visible, I thought you had to do more. I find the discovery is always in the mystery. “How?” and “Why?” are the best two questions you can ask.

Biography

Background: Born in 1941, Lake Charles, Louisiana; Lives and works between New York; Santa Fe; Kastelorizo, Greece; and Ahmedabad, India; Educated at Newcomb College, now part of Tulane University, New Orleans

Selected solo shows: 2011: New Museum, New York; 2008: Locks Gallery, Philadelphia; 2004: Cheim & Read, New York; 2003: Bass Museum of Art, Miami; 1993: Auckland City Art Gallery; 1990: High Museum of Art, Atlanta; 1975: The Kitchen, New York

Selected group shows: 2007: Circa 70: Lynda Benglis and Louise Bourgeois, Cheim & Read, New York; 2005: Summer of Love: Psychedelic Art from the 60s, Tate Liverpool; 1982: Early Work, New Museum 1981; and 1973: Whitney Biennial, New York

• To read more of our best artist interviews over the past 30 years, click here for the full collection