The high quality of the collections in Chicago’s art institutions is built on the wealth of the city’s industrialist benefactors—a lineage that dates back to the 19th and early 20th centuries. Famously, Potter Palmer (Bertha Honoré Palmer, wife of the retail magnate Potter Palmer) donated many of the works that form the Art Institute of Chicago’s (AIC’s) Impressionist collection. But while Palmer’s appetite for art and allegiance to the Art Institute, in particular, remains etched in the collective memory, the nature of collecting has been undergoing significant change in the city.

“Chicago collectors were in the vanguard in the ‘Gilded Age’. With the 1893 Columbia Exposition they were bringing the world to Chicago,” says Inge Reist, the director for the Center of Collecting in America at the Frick Collection in New York. The question that hangs in the air, however, is whether the city’s art institutions can be maintained by the next generation of collectors. A number of collectors such as Buddy Mayer, Lewis Manilow and Jerome Stone are nearing the end of their collecting careers. And, as yet, the next generation are not replicating their parents’ efforts on the same scale.

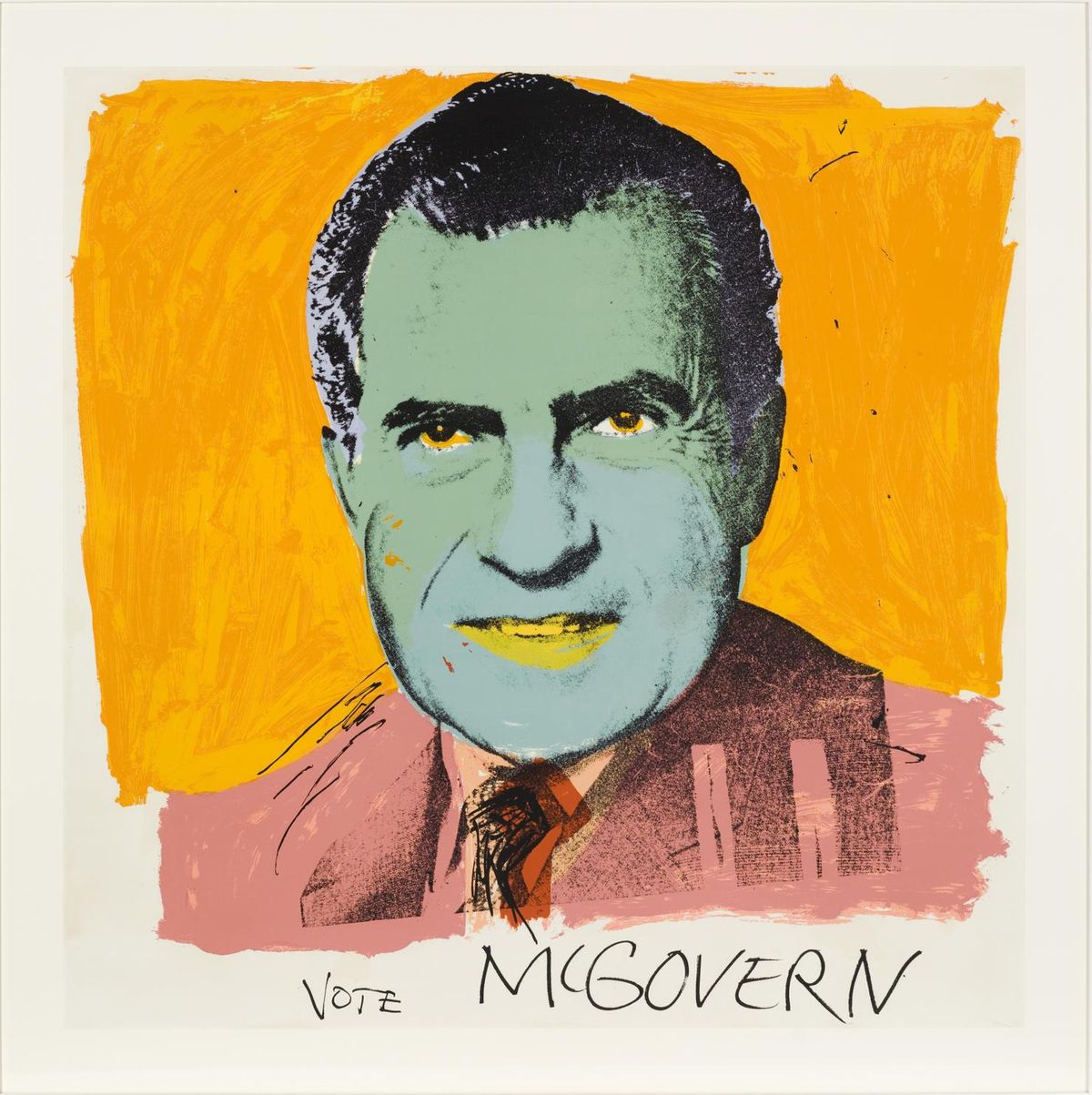

Take Beatrice “Buddy” Mayer, 87, the daughter of Nathan Cummins, the bakery and retail tycoon, who founded Sara Lee and amassed a huge Impressionist and Modern collection. With her late husband Robert, she expanded into Pop art, Colour Field painting, Kinetic sculpture and Photorealism, and their Samuel Marx-designed home Edgecliff in Winnetka had eight art galleries. Their Robert B. Mayer Family Collection was loaned to 35 museums, beginning in 1974. Beatrice’s father’s works became the Sara Lee Collection and was distributed to US museums in 2000. Over the years, Mayer has also donated many works to the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago (MCA).

Today, the paintings, sculptures and antiques that remain in her Chicago apartment are a compelling and rare combination of Impressionists and Pop art, juxtaposed with Han and Tang terracottas along with outstanding Ming and Kangxi blue and white porcelain.

“In those days, we collectors were curious about the artists reflecting our time and we shared information,” Mayer says. She and her husband found Pop embodying “a clarity, a sharpness and a relevancy to our everyday living”. They purchased Roy Lichtenstein, Larry Rivers, Red Grooms and other Pop art works from dealers Leo Castelli, Alan Stone, Richard Bellamy and Richard Gray. Today her collection is owned in partnership with her daughter and son. She says her children are not collecting the same way.

“The economy has changed things. My children are venturing forth to new young artists with different media and a lot has a social content,” she says. “I don’t know if it will last as long as Impressionism has.”

“My children are venturing forth to new young artists with different media and a lot has a social content. I don’t know if it will last as long as Impressionism has.”

James Rondeau, a contemporary art curator at the AIC, says the city has benefited from patrons who have collected movements in depth. He points to Muriel Newman with Abstract Expressionist art, Ed and Lindy Bergman with Surrealism and the Mayers with Pop art, among others.

Detail of Kara Walker's massive installation, Presenting Negro Scenes Drawn Upon My Passage through the South and Reconfigured for the Benefit of Enlightened Audiences Wherever Such May Be Found, By Myself, Missus K.E.B. Walker, Colored (1997). The is one of many donated to the MCA Chicago by local collectors Susan and Lewis Manilow Photo: Nathan Keay, © MCA Chicago

“Living in Chicago, we inherited a tradition of collecting,” says Lewis Manilow, an attorney who served as the MCA’s third president in 1982. Manilow gave a large number of his holdings to the AIC and a 150-foot Kara Walker, 20 William Kentridges and other works to the MCA. In the 1980s he and his wife also amassed works by Martin Kippenberger, Anselm Kiefer and Georg Baselitz, as they travelled across Europe. “We were the only Americans doing it; we never looked at it as an investment,” says Manilow, who also owns Indian, Greek and Roman antiquities, adding “my children are not actively collecting.”

Jerome Stone, 97, with his late first wife amassed holdings in Giacometti, Gottlieb, Chagall, De Kooning and Léger. “Léger’s 1921 Les Pecheurs was $450 at Sidney Janis,” said Mr Stone, who also recalls purchasing a 1961 Willem de Kooning oil along with a Schwitters collage and another painting for $10,000. Stone served on the MCA board for 35 years. “Then it wasn’t about trading; it was about the art,” says Ellen Belic, Stone’s daughter. Other major supporters of the MCA and AIC include Stefan Edlis and his wife Gael Neeson.

Chicago collector Jerome Stone bought Fernand Léger's Les Deux Pêcheurs (1921) for $450 in the 1950s; it sold at Sotheby's for $5.3m in 2015

Rondeau believes that the hugely expansive dimension to contemporary art per se has changed current collecting. “Contemporary art is about pluralism,” he says, adding there is no single Chicago collector who is the equivalent of former Sara Lee chief executive John Bryan. He counts 15 to 20 “serious collectors” in the city.

Nevertheless four Chicagoans new to contemporary art collecting demonstrate the astonishing degree to which local institutions have stepped up to support their efforts.

New kids on the block

“Art history for me is ten years back,” says James Cahn, 28, a financial analyst with Wanger Fund. He focuses on Neo-Formalism and has bought works by Wolfgang Tillmans and Richard Hawkins.

Other collectors, such as Jefferson Godard, 39, hone in on new media. “Video is now where photography was in the seventies,” says Godard, a professor of architecture at both Columbia and Westwood Universities. He owns video works by Guy Ben-Ner and Kara Walker. He also chairs the MCA’s “Verge” committee of young collectors.

Ten years ago Eric Lefkofsky, 39, considered his collection to be his baseball cards. He only began in the art market three years ago and his collection, although modest in size, led directly to his being named an AIC trustee in 2008. He sits on the finance committee and joined the MCA board “a few days ago”.

“I’m new to this entire world,” says Lefkofsky, a Detroit native who “did not grow up with art”, from the office of his technology firm. His collection is made up of “art that is relevant to our generation” and includes African American artists such as Kerry James Marshall. “I’m not looking at the $57m Bacon; my focus is ten works for a $1m,” he says.

Other new players include Canice Prendergast, an economist with the University of Chicago Booth School of Business, who is acquiring works for the graduate school’s Rafael Viñoly-designed building. “Access is the biggest hurdle to collectors anywhere but here it’s an advantage to be in Chicago because of the extraordinary entry points we have,” Prendergast says. He liaises with James Rondeau, Renaissance Society director Susanne Ghez, Los Angeles collector Dean Valentine and Suzanne Booth (the Booth School of Business is named after her and her husband, who donated $300m to the school) when selecting art. “In a big city like New York we would be too small a fish to get the curator of MoMA on site,” he says.

Other collectors besides Prendergast cite access to curators as essential to fine-tuning their holdings. “Any time I’m about to buy, they’ll tell me if the work is right,” Lefkofsky says. “Madeleine [Grynsztejn, MCA director] can tell in five seconds.”

“Here it’s about building a collection that you hope will end up at the MCA or on the wall of the Art Institute”

Another major factor fuelling collecting in Chicago is economic diversity. Unlike New York, which is heavily dependent on financial services, in Chicago insurance, advertising and manufacturing are still critical to the economy. “We don’t have the busts and booms nor the wild swings in housing prices like London and New York,” Prendergast says. With a greater economic stability, art is not so investment laden and there are very, very few flippers, he noted. Conversely, he points out that art in the Windy City is perceived remarkably differently than in the reigning international capitals. “Art is seen as emblematic of civic pride,” he says.

“Here it’s about building a collection that you hope will end up at the MCA or on the wall of the Art Institute,” Lefkofsky agrees. And that intent, he hopes, will secure for his city another generation ready to take its place in its long lineage of collecting and benefaction.

• Originally appeared in The Art Newspaper with the headline "Can today’s patrons live up to those of the past?"