The Victoria and Albert Museum has acquired five “medieval” miniatures produced by the notorious “Spanish Forger”, who operated a century ago. Although one of the most successful fakers in art history, his identity still remains a mystery—as does his nationality, which is probably not Spanish.

Curator Dr Mark Evans says that it is important to have examples from the Spanish Forger, “for what it tells us about late 19th-century perceptions of medieval art”. His works are now very collectable, with the V&A’s set valued at around £20,000. They were acquired under the Acceptance in Lieu system, to cover inheritance tax, from the estate of Jean Preston, a British curator of manuscripts at Princeton University.

The Spanish Forger was named from the first work identified as a fake, in 1930. This was a panel in the style of Jorge Inglés, who was active in Spain in the 1440s, but was English by birth. Since then there have been suggestions that the forger was Portuguese, Belgian, Swiss, English or, most plausibly, French. He seems to have worked over a long period, from the 1890s to the 1920s.

The number of miniatures and panel paintings attributed to the Spanish Forger has steadily grown. In 1939 it was thought to be 14. By 1978, when New York’s Morgan Library curator William Voelkle held a show, it was 150. Mr Voelkle, who is still at the Morgan, says his latest tally is 348. All are in the style of 14th- and 15th-century artists. He “suspects there are more examples in private collections and even some in museums, which have not been recognised”.

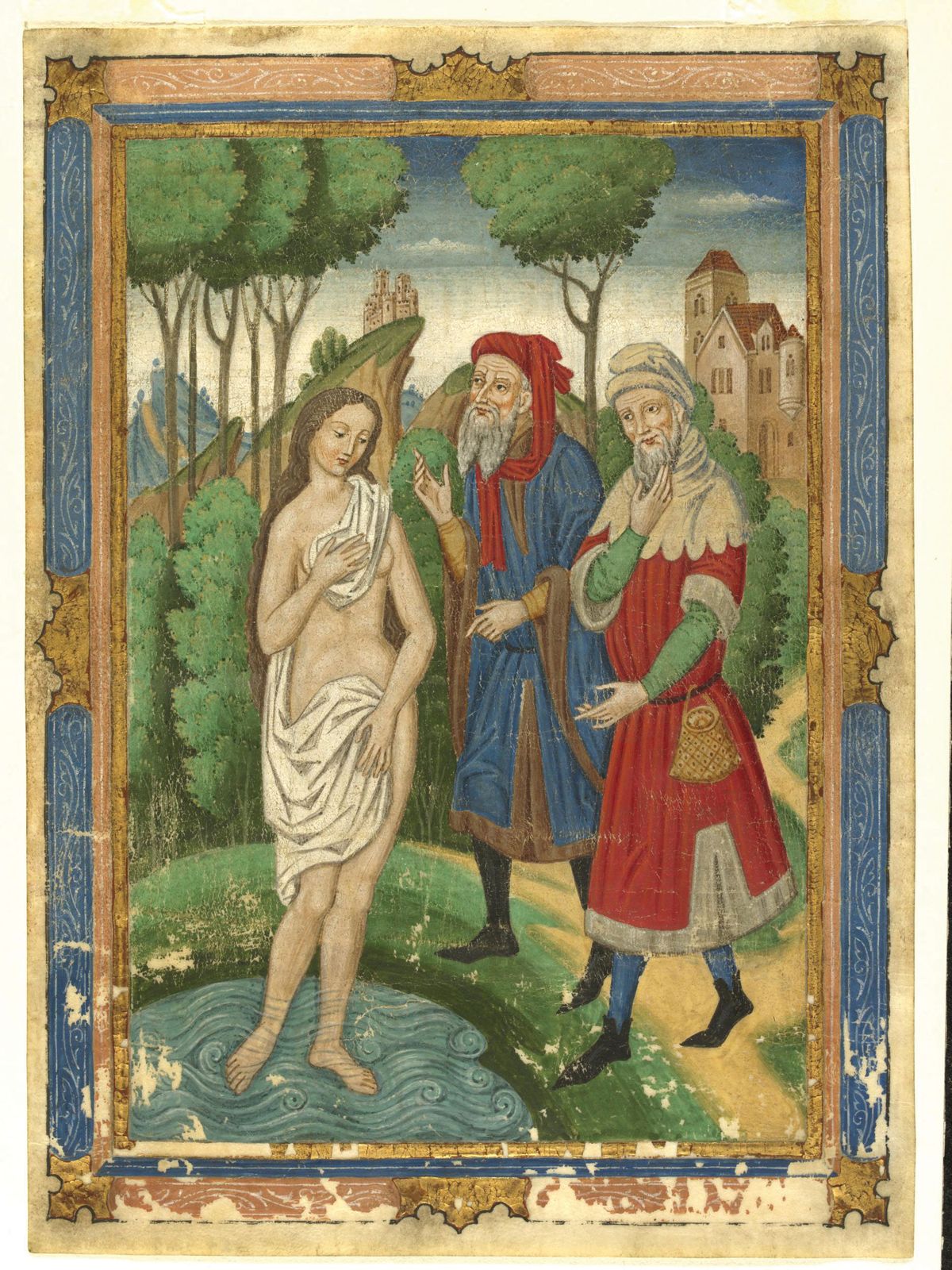

The five miniatures acquired by the V&A depict King David, Jonah and the Whale, St Michael, Susannah and the Elders, and Joseph and Potophar’s Wife.

They are on old vellum, taken from an Italian antiphony of around 1400. Music remains on the reverse, while the front has been scraped before the illuminations were added. A scientific examination by Dr Lucia Burgio confirms that modern synthetic pigments were used, such as chrome yellow, emerald green and ultramarine blue.

Like most of his miniatures, the V&A’s examples are attractive narrative images with religious overtones, although the precise incident depicted is often difficult to pin down. King David got its name because the main character plays a harp. The Spanish Forger’s faces are sweetly sentimental and fairy-tale castles often loom in the background.

He was not a mechanical copier, and would imaginatively transform elements of authentic works into his own style, rather than (as most forgers do) imitating a particular artist. His inventiveness ultimately became his undoing. In King David, the woman at the right wears a headdress in a 16th-century style, whereas the female on the left has a 15th-century one.

• Originally appeared in The Art Newspaper with the headline "‘Spanish Forger’ bought by V&A"