An investigation by The Art Newspaper has revealed the extraordinary saga behind a Leonardo da Vinci exhibition staged in Mussolini’s Italy in 1939. We have discovered that France initially promised to lend the Mona Lisa as part of a secret agreement intended to help avert war between the two countries. The political situation then deteriorated, and the Mona Lisa was never sent.

However, King George VI did loan 19 of his greatest Leonardo drawings from the Royal Collection and the Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A) sent its precious Leonardo notebooks, the Forster Codices. Several private British collectors also loaned their Leonardos, including the Duke of Buccleuch, who sent the Madonna of the Yarnwinder, the painting stolen from Drumlanrig Castle in Scotland in August 2003. The current duke told us how his father’s Leonardo was stranded in Fascist Italy for the duration of the war and revealed the untold story of how it was finally recovered.

The masterpieces were destined for the most important Leonardo exhibition ever held, the huge retrospective in Milan in 1939. The story of the diplomatic manoeuvring over the loans is revealed in files at the Royal Archives at Windsor Castle. We have also examined previously unpublished papers in the National Archives at Kew and at the V&A.

Whether a tiger is really less likely to bite you or your friends if he has been previously offered a cream bun is a point as to which I am personally sceptical.

The documents suggest that V&A director Eric Maclagan may have had a more realistic grasp of international politics than the British government, at a time when prime minister Neville Chamberlain was pursuing a strategy of “appeasement”.

When considering Italy’s request to borrow the Forster Codices, Maclagan wrote: “Whether a tiger is really less likely to bite you or your friends if he has been previously offered a cream bun is a point as to which I am personally sceptical.”

When the Milan exhibition eventually opened in May 1939, its propaganda message was clear. The catalogue introduction explained that the show was being held on the orders of the “Duce del Fascismo”, to celebrate, “on the orders of the most important living Italian [Mussolini], the most important Italian from history [Leonardo].”

On the eve of the V&A’s forthcoming Leonardo exhibition, curated by Professor Martin Kemp and opening on 14 September, we reveal the politicking behind the 1939 exhibition. The rarely-shown, light-sensitive Forster Codices, which will be the centrepiece of this year’s show, only went to Milan after an agonising last-minute decision. It was then almost caught in Italy by World War II, but was withdrawn from the Milan exhibition shortly before Britain declared war on Hitler’s Germany.

Appeasement

The story begins in late 1938, when King George VI, whose Royal Library owned the world’s greatest collection of Leonardo drawings, received a request to lend works to the Milan retrospective. This was channelled through the distinguished art historian Professor Tancred Borenius, who had been born in Finland, but then worked in London. He served on the Milan show’s “foreign commission”, acting as an intermediary to arrange loans from British owners.

The drawings had never left England since their arrival in 1630, but King George VI generously agreed to lend them, on the recommendation of Royal Librarian Owen Morshead. This was partly “an act of neighbourliness”, and also in gratitude for loans provided for the Royal Academy’s Italian exhibition in 1930, which had been arranged after the personal intervention of Mussolini.

The Milan organisers were extremely grateful for the King’s decision, and they responded with a telegram on 24 November. This thanked George VI (“the August Lender”), saying that his generosity would “profoundly stir the soul of Italy”.

The decision to lend came at a time of great tension with the Fascist powers, although it was then hoped that world war would be avoided. Two months earlier, on 29 September 1938, the Munich Agreement had been signed by the leaders of Germany, Italy, Britain and France, legitimising Hitler’s occupation of the Sudetenland (part of Czechoslovakia). UK prime minister Neville Chamberlain called the agreement “peace for our time”.

When the Prime Minster goes to Rome I should like to feel that he knows of a small gesture of friendliness that The King is about to make towards the Italians…

On 9 December, Morshead suggested that the decision to lend the royal Leonardos could be used “as conversational ammunition” during a visit which Chamberlain planned to make to meet Mussolini in Rome.

Morshead wrote to Chamberlain’s private secretary Osmund Cleverly to say that “when the Prime Minster goes to Rome I should like to feel that he knows of a small gesture of friendliness that The King is about to make towards the Italians...His Majesty has consented to lend 15 [later increased to 19] of the Leonardo drawings from Windsor. This does not happen to have been announced yet, but there is no objection to Mr Chamberlain’s mentioning it [to his Italian hosts].” Chamberlain’s visit took place on 10 January 1939, with the British delegation hoping that their intervention would prevent Italian expansion in the Mediterranean.

Morshead’s letter to Downing Street of 9 December 1938 also included an astonishing revelation: the Louvre had agreed to lend the Mona Lisa, as well as The Virgin of the Rocks. The Mona Lisa had only once ever left the Louvre: it was stolen in 1911 and after being recovered in Florence in 1913 it was exhibited for a few days in Italy before being returned to Paris.

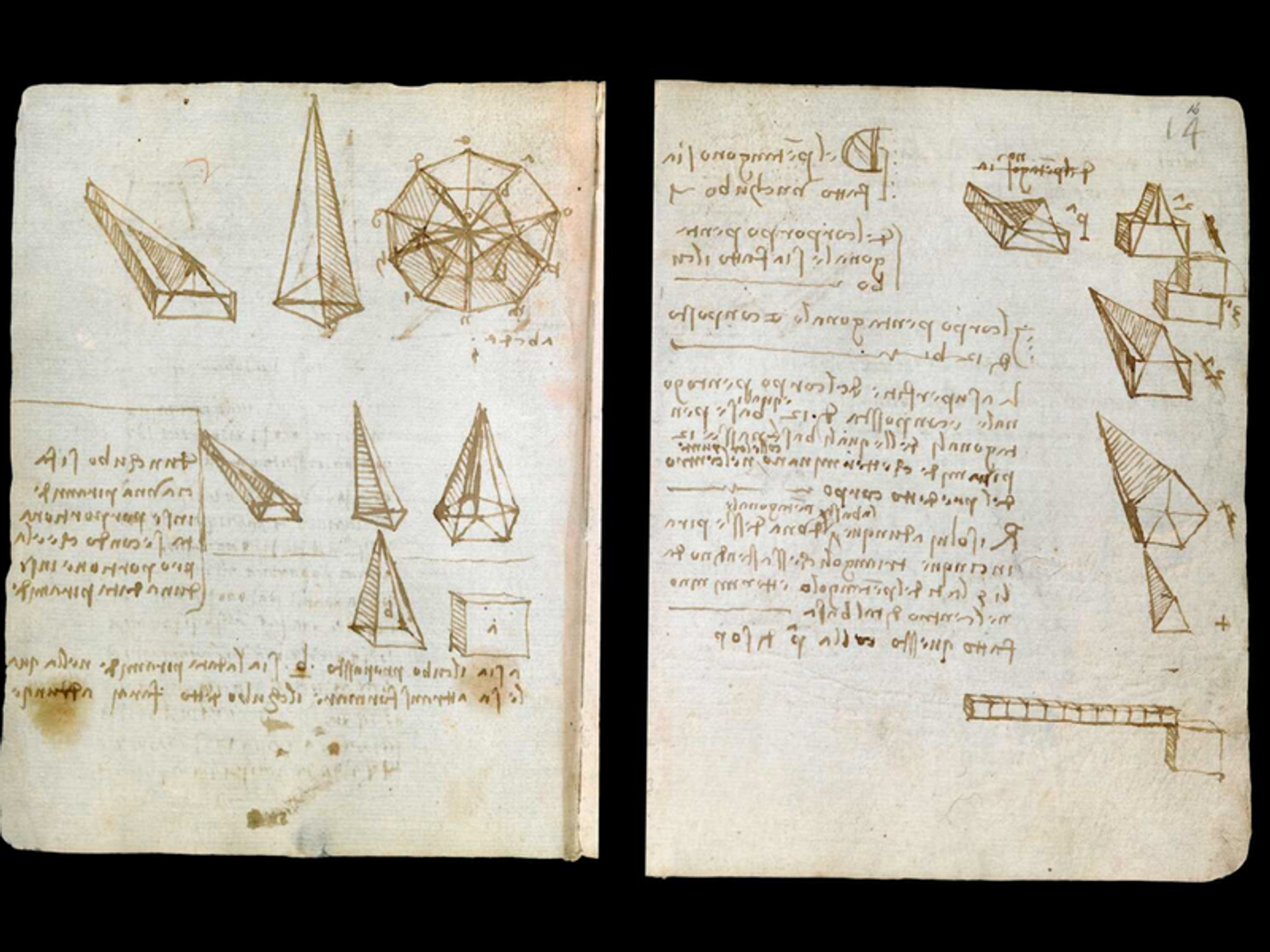

Pages from the V&A's Forster Codices Victoria and Albert National Art Library, Museum no. MSL/1876/Forster/141/I

V&A notebooks

Having secured the King’s Leonardo drawings, Borenius turned his attention to the V&A. On 27 January 1939 he wrote to the museum asking for the loan of the Forster Codices, “subject to no dramatic changes taking place in the European situation”. The Leonardo notebooks, named after John Forster and bound into three volumes, had been bequeathed to the museum in 1876. Dating from 1487-1505, they comprise numerous artistic and engineering sketches, together with text in mirror writing.

Following the loan request, V&A director Eric Maclagan contacted the Board of Education, the government body responsible for the museum. The matter needed very careful consideration, since the Forster Codices was “as important an application for a loan as could well be made to us”—it was regarded as the most important single object in the museum.

Maclagan pointed out: “Owing to the fact that the King is lending, we may probably assume that the Foreign Office is anxious to do anything possible to please the Italians in this respect.” He then compared the Leonardo loan to offering a “cream bun to a tiger”.

Meanwhile, the international situation was deteriorating rapidly. Hitler was not satisfied with just taking the Sudetenland, and on 16 March 1939 he occupied the rest of Czechoslovakia.

On 27 March, Milan’s exhibition representative Borenius wrote to the V&A director, saying that the French government had just confirmed that it would lend the Mona Lisa and The Virgin of the Rocks. He commented: “You will realise the immense significance of this decision coming at the present juncture. In the circumstances a relatively small fact like this assumes, I think, the importance of a definitive assurance that there will be no war between France and Italy.”

International tensions then worsened, and on 7 April Mussolini invaded Albania. The V&A was now extremely worried. Shortly afterwards the French Government decided that the Leonardos should only be lent by the Louvre in return for Italian paintings of at least equivalent value, and this proved impossible to arrange. Both the Mona Lisa and The Virgin of the Rocks remained in Paris, although lesser works were to be lent to Milan.

Maclagan wrote on 22 April to Foreign Office librarian Sir Stephen Gaselee, explaining the V&A’s position: “If the King lends, I do not think the Museum can possibly refuse; if, on the other hand, the King refuses to lend, I feel most strongly that we ought not to run the risks involved.”

Excuse

British officials then came up with a convenient excuse why the Leonardos could only be lent for a short period, not for the entire run of the Milan exhibition which was scheduled to close on 20 October 1939.

The 15th International Congress of the History of Art was to be held in London in July, and participants were due to visit the Royal Library in Windsor on 28 July. It was therefore pointed out that there would be great disappointment if 19 of the King’s Leonardo drawings were not available.

At the end of April there was only a fortnight to go before the opening of the Milan show, and a final decision had still not been made on the British loans. It was George VI who then gave his approval, following the advice of Foreign Office Secretary of State Lord Halifax.

On 27 April the King’s private secretary, Sir Alexander Hardinge, wrote to Royal Librarian Morshead with the news: “The King has decided, after consultation with the Foreign Office, that it would be inadvisable to break the promise given to the Italian Government after the signing of the Anglo-Italian Agreement. His Majesty, therefore, agrees to the drawings being sent as arranged, but he thinks that the excuse of the International Congress of the History of Art can well be used for getting the drawings back by the middle of July...In the event of a really dangerous situation arising between this country and Italy, His Majesty would telegraph to the King of Italy asking him to make himself personally responsible for the safety of the drawings.”

Fascist party officials at the exhibition opening, including secretary general Achille Starace, in white

Opening

On 3 May, the V&A handed over the Forster Codices, packed in a wooden box, to Borenius, who took the notebooks to Milan, insured for £39,000. He also carried the Leonardo drawings, which were insured for a slightly higher sum. The “Mostra di Leonardo da Vinci” opened at Milan’s Palazzo dell’Arte on 9 May. On 22 May Italy and Germany signed a military alliance, known as the Pact of Steel, and Europe moved closer to war.

As previously arranged, the Forster Codices and the royal drawings were withdrawn from the Milan exhibition on 15 July. Borenius, travelling as an Italian diplomatic courier, returned to London with the precious exhibits.

On 31 August, Hitler ordered the invasion of Poland, with Britain and France declaring war on Germany on 3 September. World War II had broken out, although Italy was not yet involved.

The Leonardo show continued until 20 October 1939. Although George VI and the V&A had withdrawn their loans in July, the works of other British private owners were stranded in Italy, as it was too unsafe to transport them back to Britain. On 11 June 1940, Italy declared war on Britain.

• We acknowledge permission of Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II for consultation of the Royal Archives.