Paula Rego’s psychologically-charged and subversively-suggestive paintings are utterly unique and have won her a huge and appreciative audience from all artistic camps, from Charles Saatchi, who is one of her keenest patrons and admirers, to the trustees of the National Gallery who made her the first artist in residence in 1990 and commissioned her to paint an enormous mural, Crivelli’s Garden, for its restaurant.

Now in her late 60s, Rego is far too playful and unpredictable to assume the mantle of grande dame, but she is also no naïf. Her paintings—and they are paintings, even though she has worked solely in pastel since 1994—are complex, multi-referential and highly sophisticated.

In the spirit of the Surrealist artists she loves, and infused with the carnivalesque culture of her native Portugal, anything and everything is possible in the work of this mistress of the skewed narrative, while at the same time utterly plausible, thanks to her rigourous pictorial judgement and precision. This is an artist who refuses to rest on any kind of laurels, but who tirelessly stretches her art to pose new challenges for herself and the viewer.

The Art Newspaper: A major part of this new show is based around the story of Jane Eyre, what brought you to the story?

Paula Rego: It’s the best story of all time! I came to Jane Eyre through that wonderful book The Wide Sargasso Sea (1966) by Jean Rhys. In Rhys’s book the woman is always the victim, which irritates you in the end. The thing about Jane Eyre is that she’s not a victim, she’s so resourceful and she looks after herself really well. The others treat her so badly, really, so badly.

It’s very much a woman’s world that you present, but you are also very tender towards your men, even if they are monstrous, they always possess a certain vulnerability.

You like to keep them vulnerable so that you can control them better...[much laughter] But all this is in pictures, it’s not like what we do in life.

Many of these works are lithographs, a technique you used when you were a student at the Slade School of Fine Art. What made you return to it after all these years?

I did make etchings, but I wanted to do something a bit bigger; making lithographs is a little like drawing, working on the stone is extraordinarily exciting and sensual.

You’ve made prints throughout your career, what is it that appeals to you about them?

Prints are a great release because you can make them very quickly. I always like to have some print on the go nowadays. I used to do just one thing at a time, now I have several things always on the go. It is also addictive, once you start making one or two, very often you find that you want more and more and you cannot stop.

[Prints are] also addictive, once you start making one or two, very often you find that you want more and more and you cannot stop

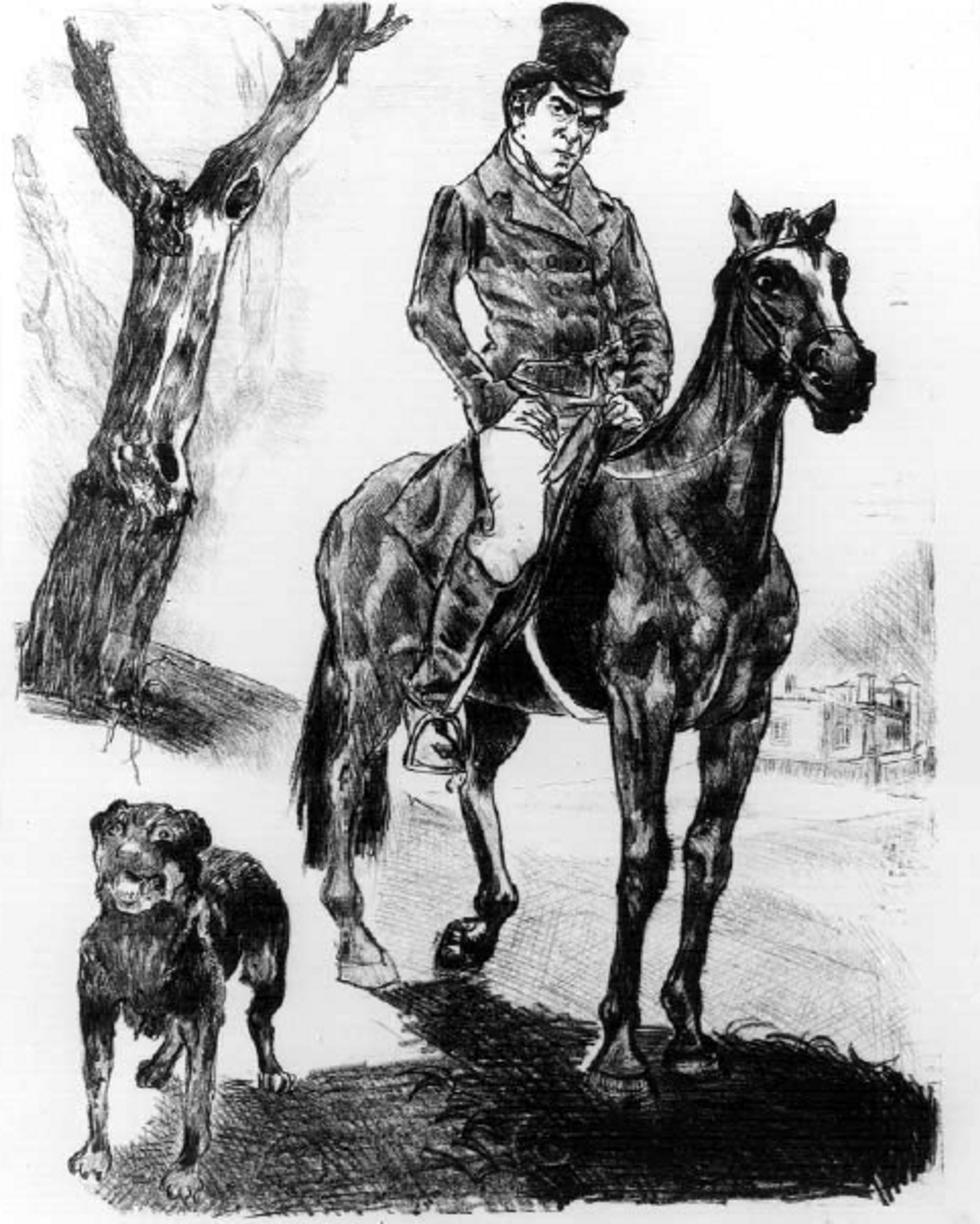

Rego, Mr Rochester, 2002 © Paula Rego

What makes it so addictive?

The effects you can get. When I was little there were those transfer papers that you put in water and then you put upside down on a piece of paper and then you lifted the top and there was an image there and you were not sure what it was. Doing prints is like that, because we never know what is going to come out.

This combination of technical precision and the completely extraordinary chance things that the printing process can throw up seems very much in keeping with the combination of pictorial rigour and imaginative freedom that I see underpinning all of your work.

When I was doing The Dance (1988), which took me six months, I stayed there the entire time doing that damn picture. Everything was all bottled up. When I started doing the nursery rhymes, they all just came out, thousands of them. That happens now and again. At the Slade very often you went into the print room as an escape from having to do art, you could do what you wanted in there, it was not like such big, serious stuff, so you could just have fun and play.

A sense of playfulness seems to lie at the core of everything you do, although the games can become very dark.

Yes, my need to draw is very important to me. It has helped me get through some difficult situations, particularly at the Slade. Nevertheless, you also have to play.

You always draw from the model now, don’t you?

I draw with the model in front of me as I have to copy. I don’t do studies at all, I start straight on the panel, but I do do studies if it is a big composition, like The Dance, Celestina or The Families.

Since the mid-1990s you have worked in pastel but the act of drawing has always been key, hasn’t it? You practise every day?

Every day, not just for the sake of practising, but because the doing of it is important. There was something that used to be called something like “The practised hand” which then became terribly despised because it was thought that if the hand was practised then somehow it did not connect as purely to your imagination, it was like the idea of the noble savage; things had to come out of you spontaneously and cack-handedly. But they don’t, and if you get better at what you do, it does not mean it is any less spontaneous.

You’ve said that drawing brings the inside out, that good drawing is “about being alive”.

There are two kinds of drawings: there is the kind of drawing where you look inside yourself and then express yourself through the hand so that the hand becomes the barometer or the seismograph, and then there’s the drawing where you observe what’s in front of you and record it through your hand. This act of recording is astonishing, every time I do it, I can’t believe I’ve done it. It comes from a lot of practice.

Does what emerges in your art ever surprise you?

It is very interesting because it reveals to you certain things about certain situations that you didn’t see before. Sometimes these things are unacceptable, they are not very nice things about yourself revealed in pictures. One does it because one enjoys seeing what one should not see.

Since 1994 all your major works are in pastel on sheets of paper backed onto sheets of steel, why did you switch from painting to this method?

Pastel is like drawing and painting at the same time and you can change things very easily. I do not use pastels like they are traditionally used, they are never rubbed or anything, and so it’s drawing on drawing on drawing... I am not interested in getting an effect, it’s very much drawn and it’s very easy to rub out if it’s wrong and start again. I’ve even got to the point of washing it. It’s watercolour paper bound on steel, it’s very tough.

While you’ll talk freely about what you see in your pictures, you tend to steer clear of categorical explanations.

Well these change, people read their own stories into pictures, anyway, and I change what I say constantly. I forget, and years later, you never know how you might interpret something. It’s so astonishing when you discover what you have done. Sometimes you are so very disconcerted! I thought I had painted a picture of a magical ant and a chicken but it turned out to be my mother and my father! It’s really amazing!

It’s so astonishing when you discover what you have done... I thought I had painted a picture of a magical ant and a chicken but it turned out to be my mother and my father!

In your recent painting War, you’ve returned to depicting animals although, true to your commitment to working from life, the main rabbit protagonists are drawn from models that you’ve made with specially constructed folded paper and papier mâché heads. Why use animals here?

Sometimes there are things that you cannot do with people, when it is something like war, it’s not possible unless you are Goya. I have not seen these things for real, I’ve seen men beating their wives, but I don’t want to represent that. It seems less extreme if you put a man there, while if you put a monkey it’s also ridiculous.

Charles Saatchi has been a major patron and has a number of your works on show in the new County Hall Gallery, what do you feel about your work being there?

The pictures have a different role to play in there from anywhere else I’ve ever seen them. They have a much harder job to do than they do in a place which is all white. The role they play there is rather mysterious, you might see them escaping down the corridors as you might see the White Rabbit coming in and out of those corridors. I thought, God, I’m going to see this white rabbit, just walking in and out, Charles Saatchi himself.

I think it is quite a good, mysterious, unexpected, bizarre, place to have pictures and we will just have to get used to it and just have to see how the pictures continue to work. It’s a test for the pictures, dammit! It’s a bloody test for the works of art! It is like looking at pictures in black and white and that is how you can tell if they are good or bad. It is a test because the pictures are the most difficult things to hang in there. You don’t know what you are going to see in there, what is going to happen? What happens behind those doors? What happens behind the panelling? The place is like Surrealism in action, you do not need any art in there!

Biography

Background: 1935 in Lisbon. Lives and works in London. Education: 1952-56 Slade School of Fine Art, London

Currently showing: Marlborough Gallery, London, 15 October-22 November

Solo exhibitions include: 2001-2002: Celestina’s house, Abbot Hall Art Gallery, Kendal; travelling to the Yale Center for British Art,Connecticut; 2001: Só Desenhos: Paula Rego, Fundação Arpad Szenes – Vieira da Silva Institute, Lisbon; 1998: The Sins of Father Amaro, Dulwich Picture Gallery, London; 1997: Retrospective exhibition, Tate Gallery Liverpool, Fundação das Descobertas, Centro Cultural de Belém, Lisbon; 1996-97: Paula Rego New York, Marlborough Gallery Inc., New York; 1994: Dog Woman, Marlborough Fine Art, London; 1992-3: Peter Pan & Other Stories, Marlborough Fine Art, London; 1991-92: The National Gallery, London; Laing Art Gallery, Newcastle; Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation, Lisbon

• To read more of our best artist interviews over the past 30 years, click here for the full collection