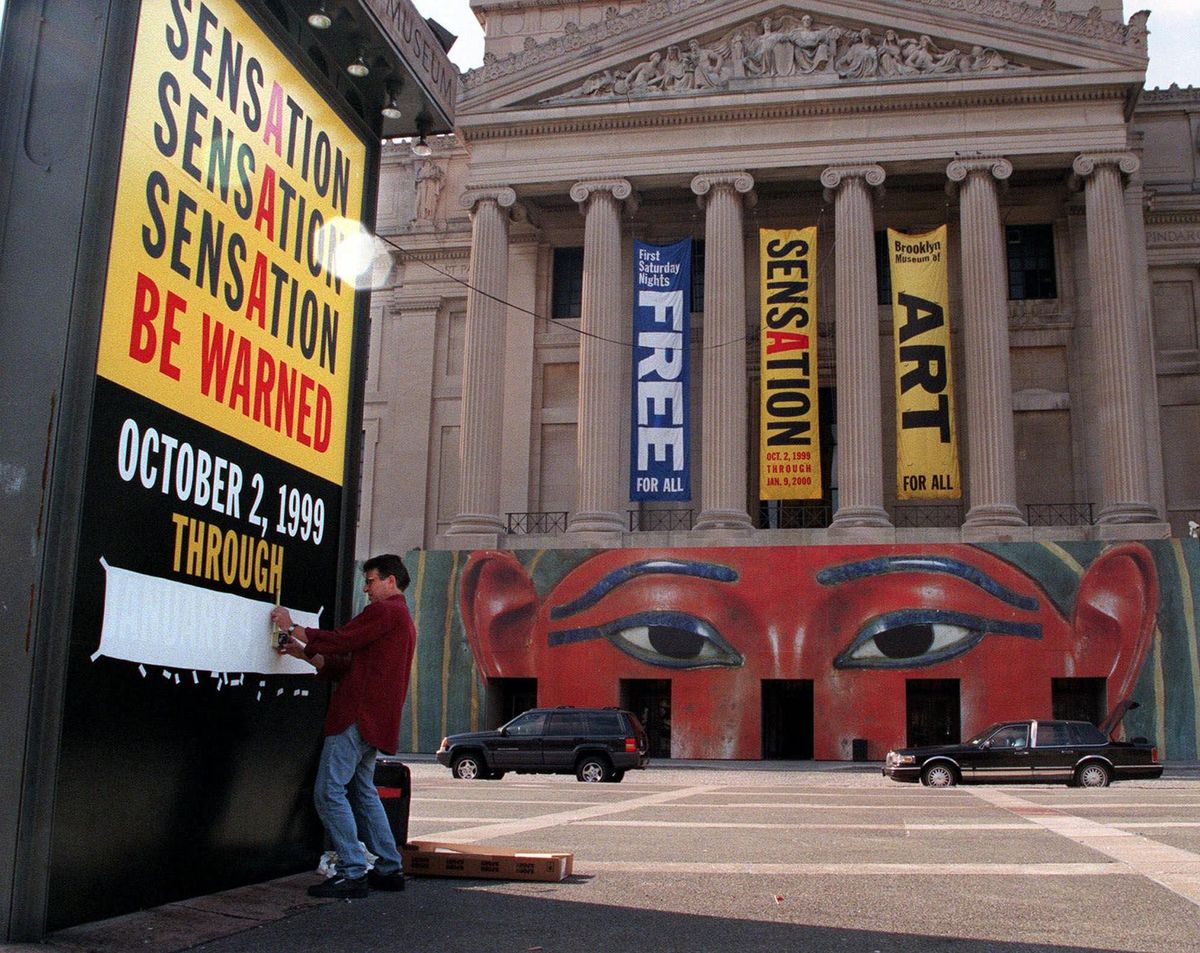

Are museums overstepping the ethical line and sacrificing their freedom of action and thought in their search for sponsorship? The Art Newspaper has looked beyond the recent case of the Brooklyn Museum and the "Sensation" exhibition into other sponsorship deals and has discovered a disquieting trend.

Brooklyn continues to be stigmatised for soliciting and using money from the collector Charles Saatchi ($168,000) to put his works of art on view, and for giving Saatchi carte blanche to install and identify the works, bypassing its own curatorial staff.

The exhibition was also sponsored to the tune of $50,000 by Christie’s, which had sold work for the collector in the past and hopes to do so in the future. Court documents reveal that [the Brooklyn Museum director Arnold] Lehman had intimated that art from the Brooklyn Museum might also go on the block at Christie’s. The auction house has supported exhibitions at other museums, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, usually with $10,000 to $20,000 grants for catalogue publication.

Besides citing its constitutional rights, Brooklyn pleaded innocent to charges of any ethical misdemeanour and said that sponsors for contemporary art are few, especially for $2m shows like "Sensation". Lehman had indeed been turned down by a firm that looked like an ideal fit, the manufacturer of Trojan condoms. Moreover, the museum said, Christie’s had already funded the show at its original venue, London's Royal Academy of Arts, in which Saatchi also played a role.

The Guggenheim Museum’s 1998 exhibition of motorcycles curated by its bike-riding director was underwritten by BMW, the manufacturers of the machine shown on the cover of the catalogue. Critics said that the Guggenheim placed the needs of the market over its mission as soon as a source of corporate funding appeared. This autumn, the museum will be exhibiting 250 costume designs by Giorgio Armani, a show which the museum announced soon after Armani signed on to be a five-year sponsor with a gift of $5m.

James Abruzzo of the A.T. Kearney Company in New York, which advises business and non-profit institutions, extolled the advantages of sponsorship: “Look at what Christie’s did for a very limited amount of money. Look at what Saatchi did. This is a very inexpensive purchase of extremely high visibility. The whole thing is commercial, and there's nothing wrong with it. There should be a healthy quid pro quo.” Contemporary art is a bargain for sponsors, he added, and he expects more firms in internet and fashion to join the field.

Media sponsorship is another area where there can easily be a conflict of interest. Time Out New York sponsored “Sensation,” which its critic supported, and many critics panned. In smaller cities which treat museum exhibitions as enterprises of civic pride, critics whose employers sponsor exhibitions might be loathe to attack a show.

The most frequent conflicts of interest occur in the fields of high-technology and industrial and decorative arts, where manufacturers fight to distinguish their products by giving them the stamp of novelty or history. Among the worst offenders are science museums that permit firms to fund and design installations that are themed around corporate mantras. Critics call this the "coal dust is good" syndrome. Disney has designed its Epcot Center in Orlando, Florida, around just such an approach.

Both the American Association of Museums (AAM) and the Association of Art Museum Directors (AAMD) have no written guidelines detailing ethical practices in the area of corporate sponsorship of non-profit exhibitions. Mimi Gaudieri, the executive director of the New York-based AAMD, revealed that the recent Shiseido gift to the Grey Art Gallery as well as the Armani donation to the Guggenheim have given a number of their members cause for concern. Gaudieri also confirmed that fundraising and financing was at the top of the agenda for the association’s mid-winter meeting, scheduled for the end last month. The completion of a set guidelines, however, could take as long as six months. At the same time, the Washington DC-based AAM has set up an ad hoc committee to draw up recommendations on the same topic.

In the US, insiders warn that the appearance of a conflict of interest could invite regulation of sponsorship—and urge museums to avoid giving any impression that their galleries are for sale or for rent

Public officials such as the mayor of New York say they are appalled to see corporations exploiting sponsorship, but if museums are urged to raise more money by politicians who cut their budgets (and this is equally true for Europe), should they be criticised for doing just that? In the US, insiders warn that the appearance of a conflict of interest could invite regulation of sponsorship—a political overview of any grant of more than $250,000, for example—and urge museums to avoid giving any impression that their galleries are for sale or for rent.

Other cases

Grey Art Gallery, New York University “Face to Face: Shiseido Japan 1900-2000” : The Japanese cosmetics firm Shiseido has given $500,000, the largest donation to the gallery since it was founded in 1975, and at the same time the Grey is preparing the exhibition “Face to Face”, focusing on the history of makeup and its impact culturally and socially in Japan (15 September-28 October). In the exhibition there will be Shiseido posters, products and packaged goods along with the company’s fine and decorative art objects. Shiseido is the world’s fourth largest cosmetic firm, with annual net sales of more than $5bn. Its gift to the endowment is intended for programmes and exhibitions. In addition to this, Shiseido has promised to pay for the entire cost of the exhibition. Although the gallery’s curator, Gumpert, refers to the timing of the gift and the planning of the exhibition as “kind of simultaneous,” she hastens to add that she feels it is no more than coincidence. “What is important is the integrity of the exhibition,” she explains. “Shiseido has no undue influence in a show which explores East and West relationships as well as concepts of gender and beauty. It will be presented in a scholarly manner, and it is an exhibition I would do even without a major gift involved.” Works from other institutions will also be borrowed for the exhibition. Gumpert had worked with Shiseido prior to joining the museum three years ago. Versions of “Face to Face” were paid for by Shiseido to be exhibited in Tokyo two years ago and at the Musée des Arts Decoratifs in Paris three years ago. In both of these exhibitions, Shiseido’s packaged cosmetic goods were featured.

Brooklyn Museum, “Sigmar Polke”: Sponsored by the Gagosian Gallery, which does not represent Sigmar Polke. Yet for any dealer seeking to enter the world of Polke collectors, who might be thinking of selling on the secondary market, this is a shrewd sponsorship.

Guggenheim, “China—5,000 years”: Did Guggenheim curators water down the modern half of this 1998 show, avoiding contemporary artists viewed with disfavour by the regime? Certainly, recently excavated antiquities hardly count as Modern art. But the museum needed the Chinese government's co-operation and the firms sponsoring it (Nokia, Ford, etc.) needed access to the huge Chinese market.

Metropolitan Museum of Art: While it does not allow sponsors to display products such as automobiles in the Great Hall or place corporate logos on banners outside, the museum does allow firms to fund shows of their own products. According to a museum spokesman, the problem with monographic shows of either costume (Versace, Natori, Christian Dior) or living decorative arts (Fabergé, Tiffany, Cartier—a show initiated by the British Museum, where it was also funded by Cartier) is that no firm will fund an exhibition with another company's name on it.

Los Angeles County Museum of Art, “Salvatore Ferragamo—the Art of the Shoe (1927-60)”: Reviled as the symbol of corporate design exhibitions in the 1990s, the exhibition showed 199 shoes from the Ferragamo archives in Florence. Before condemning Hollywood for its commercialism, remember that this exhibition was first shown in Florence and London.

• Originally appeared in The Art Newspaper with the headline "Show me the money"