With the lawyers on each side pleading their case to the US Supreme Court on 31 March, the eight-year battle over whether Congress can impose a “decency” test on art funded by the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) is reaching its end. But rather than raising hopes that they might deal a decisive slap in the face to Congressional limits on artistic expression, the Justices gave no clear indication of where they were heading in the case, grilling the lawyers for both sides equally. They suggested that they may dispose of the lawsuit without even getting to the core issue of whether the decency test is an abridgement of free speech forbidden by the US Constitution.

At issue is a 1990 statute requiring the NEA, in awarding arts grants, to take into consideration “general standards of decency and respect for the diverse beliefs and values of the American public.” Two federal courts struck down the language, which Congress enacted in outrage after the NEA funded homo-erotic photographs by Robert Mapplethorpe and a photo of a crucifix in the urine of artist Andres Serrano.

As the debate got underway, attempts by counsel on both sides to present cogent arguments were quickly deflated by needle-sharp questions from the Justices. Surprisingly, despite hundreds of pages of legal briefs on the free speech issue, the Justices repeatedly asked whether the artists had suffered enough damage to be in court at all.

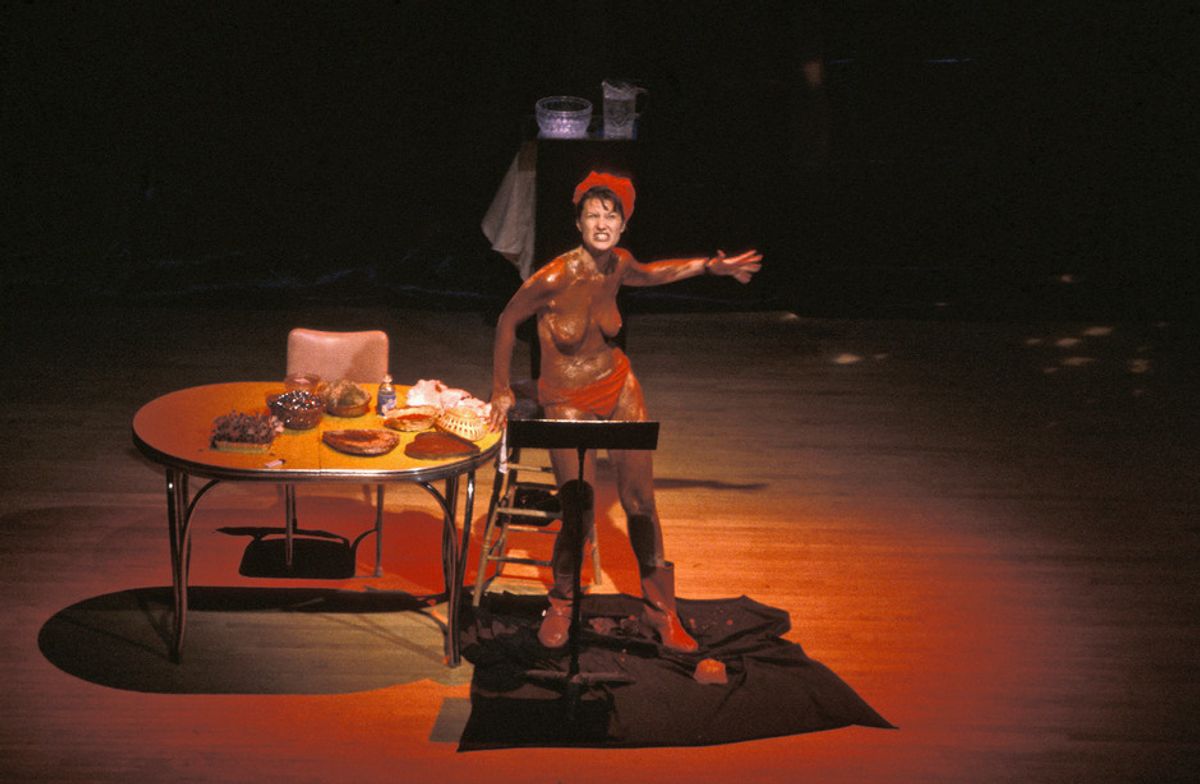

In 1990, the four artists, including Karen Finley, who smeared her nude body with chocolate while uttering “God is death”, were denied NEA grants for performances involving homosexuality, nudity, urination and AIDS. But later, they did receive grants for similar projects, and roughly $250,000 in settlement from the government for the denied grants.

“Is there an injury?” Justice Breyer asked. Other Justices echoed the question.

Seth Waxman, the US Solicitor General, defended the law, saying that decency is not categorically required of each arts application, but only had to be taken “into consideration.” He said the NEA had achieved this through “extremely diverse” application review panels. But the Justices seemed to doubt that the law left as much latitude as he said.

“Are you trying to tell us”, Justice Stevens asked, “that after the statute was passed, Andres Serrano would have the same chance of getting a grant?”

Justice Ruth Bader Ginsberg said that if a faithful NEA executive were trying to carry out the will of Congress, “the message that comes from this is, don’t fund Serrano or Mapplethorpe.”

If the panels were not enough, the Solicitor General argued, the NEA should be allowed to define “decency” and “respect better.” But several Justices jumped on him for this. “Hasn’t it had eight years to do that?” asked Justice Souter.

The government also maintains that the decency clause does not restrict viewpoint, but only “the mode and form” of expression. Restrictions on vulgar language have been allowed at public schools.

But it may be more difficult to separate mode and message in the visual arts.

“I would think that most artists would say that they are interested in mode of expression”, Justice Kennedy said.

The Justices toughly challenged the artists’ lawyer, David Cole of Georgetown University Law Center.

Mr Cole relied on the recent Rosenberger case, which held that a public university that had funded almost all student newspapers to encourage private speech could not deny funds to a newspaper because of its religious viewpoint.

But Chief Justice Rehnquist said that case was “quite different” because of the selectivity involved in NEA grants.

“There is a difference between an award, a prize, a grant”, Justice Ginsberg told Mr Cole.

Justice Breyer asked if the Constitution required the NEA to fund “a very good work of art” by the Ku Klux Klan, an American racist organization. “Do we have to exhibit it in the government courthouse? Do they have to exhibit my example in a schoolhouse?”

But Mr Cole stuck to his guns, saying the government cannot “set up a funding program” and then deny grants based on viewpoint. He distinguished NEA grants from government purchases or speech in schools.

Reading the minds of the august Justices is not easy. A Justice who appears to be harassing a lawyer may actually be pushing him to say what is needed to convince other Justices, a former public information officer for the Court, Barrett McGurn, said in a speech at the Cosmos Club in Washington the night before the NEA argument.

But attorney James Fitzpatrick, who filed a “friend of the court” brief against the decency law for twenty-six groups including the Museum of Modern Art, the American Association of Museums and the Association of Art Museum Directors, said that “none of the Justices seemed to embrace the artists’ free speech argument”, instead seemingly “going to great lengths” to avoid a constitutional decision.

The Justices will decide by June, quite possibly using a number of concurring opinions to reconcile their reactions.

• This article originally ran in The Art Newspaper with the headline "Justice apparently beside the point"