Some of our favourite Van Goghs are not the real thing, according to new evidence. Claims are being made that fakes hang in many of the world’s leading museums, including such great institutions as the Metropolitan Museum and the Musée d’Orsay, and even the Van Gogh Museum. Other experts are equally convinced of the authenticity of the questioned paintings.

Vincent van Gogh may well have been forged “more frequently than any other modern master,” according to John Rewald, the greatest scholar of Impressionism and Post-Impressionism. Rewald added that there have certainly been “more heated discussions and differences of opinion, more experts attacking other experts” over the authenticity of Van Gogh’s work than that of any other artist of the period. The American scholar, who died three years ago, would not have been surprised by the furore over Jardin à Auvers, which failed to sell in Paris last December. The debate over the painting’s attribution was testimony to the passions aroused over Van Gogh’s work, as well as a reminder of the huge sums of money which can be at stake.

The number of paintings attributed to Van Gogh far exceeds the amount of work he could have done in the 70 days he stayed there before his deathJan Hulsker

Jan Hulsker, the doyen of Van Gogh studies, claims that the artist’s accepted oeuvre is littered with fakes. In The new complete Van Gogh, published late last year (J.M. Meulenhoff/John Benjamins), the Canadian-based Dutch expert admitted that “not all the works reproduced here should be considered authentic.” Citing Van Gogh’s period in Auvers-sur-Oise, he pointed out that “the number of paintings attributed to Van Gogh far exceeds the amount of work he could have done in the 70 days he stayed there before his death.” Mr Hulsker catalogues 76 oil paintings from Auvers, which represents just over one a day.

At first glance, Mr Hulsker has failed to weed out the fakes since the first edition of his catalogue was published in 1977. Out of 2,125 works, only two have been dropped, a townscape of Amsterdam (H945; works are referred to by Husker catalogue numbers) and a portrait of a Parisian woman (H1205). But a closer examination reveals a rather different story. In contrast to the 1977 edition, a number of the listed works now have question marks after their date. Most catalogue users would assume from this that Mr Hulsker is uncertain of the dating, but he told The Art Newspaper that these are cases where he is “very doubtful” about the authenticity of the works.

Top catalogue questions 45 paintings

Mr Hulsker questions no fewer than 45 paintings and drawings, including world famous works such as the Metropolitan Museum’s Arlésienne (H1624) and the Musée d’Orsay’s Dr Gachet (H2014). Others are in the Kroller-Müller Museum (H371, 390), the Boijmans van Beuningen Museum (H1497a), Oslo’s National Gallery (H1780) and Lille’s Musée des Beaux-Arts (H2095).

Perhaps most surprising is that 16 of the 45 questioned works are at the Van Gogh Museum itself. Because nearly all the Amsterdam museum’s pictures came from the collection of Theo van Gogh, brother of the artist, their authenticity has generally been assumed.

Unfortunately, Mr Hulsker does not explain the reasons for his doubts in The New Complete Van Gogh. To question the authenticity of a work in a publication which describes itself as a catalogue raisonnée is obviously damaging to the reputation of the picture. But by failing to give the reasons for his doubts, it is difficult for curators and scholars to respond.

Mr Hulsker argues that he is drawing attention to a problem which goes far deeper. He told The Art Newspaper that in addition to the 45 Van Goghs questioned in his latest catalogue, he has “very strong doubts about the authenticity of many more works.”

Why then do there appear to be so many Van Gogh fakes? The obvious answer is money. Although Van Gogh was unable to sell his work, within two decades of his death his pictures were already selling for large sums. By the 1920s, Van Gogh had already been established as one of the most expensive modern artists. Since then prices have spiralled upwards, continually breaking the records.

Van Gogh’s failure to sell his work in his lifetime also means that there are no contemporary dealers’ records which can be used for authentication. Although Vincent gave most of his paintings to his brother Theo, he also presented pictures to friends, while some were exchanged with fellow artists and others simply abandoned. All this provided later fakers with convenient stories to explain the emergence of unknown works.

The first scandal, in 1932

Theo died just seven months after Vincent, and his widow Jo Bonger had had very little direct contact with the artist. Nearly all that she knew about Vincent and his work came from what she had been told by Theo. Despite Jo Bonger’s vigorous efforts to preserve Van Gogh’s reputation, it was not easy to question the authenticity of works which did not come from the family collection. Sometimes Van Gogh had made replicas of paintings for friends or sitters, so fakers could do other versions of authentic works. Van Gogh sketched extensively, and fake paintings could be based on authentic drawings. Van Gogh’s letters were published, so fakers could base a work on a lost painting mentioned in the correspondence.

It was three years after Jo Bonger’s death that the Wacker fakes scandal broke. In January 1928, a major exhibition of Van Gogh paintings was held at Paul Cassirer’s gallery in Berlin, with many works coming from another dealer, Otto Wacker. These previously unknown Wacker pictures were said to have belonged to a mysterious Russian aristocrat who had fled to Switzerland and who could not be named because his family would face persecution from the Soviet authorities. Although accepted by Van Gogh scholar Baart de la Faille, who had published his first catalogue raisonnée a few months earlier, the Wacker paintings were quickly denounced as fakes when they went on show. Wacker was charged with fraud and in 1932 he was sentenced to 19 months’ imprisonment.

De la Faille issued an addendum to his catalogue, rejecting the fakes and in 1939 he published a second edition of his catalogue. After the war he began work on a third edition, but this remained uncompleted on his death in 1959 and his draft was revised by a committee of experts and eventually published in 1970. De la Faille still remains the definitive Van Gogh catalogue. Seven years later Mr Hulsker produced the first edition of his catalogue, which presents paintings and drawings together in a clearer chronological presentation.

There is now growing concern that further fakes still need to be weeded out, despite the efforts of the two main Van Gogh cataloguers. The most serious work in this field is being undertaken by Dr Roland Dorn and Walter Feilchenfeldt, both acknowledged experts. German art historian Dr Dorn wrote his thesis on Van Gogh’s Arles paintings and he has curated the exhibitions Vincent van Gogh and the Modern movement (Essen and Amsterdam, 1990-91) and Van Gogh and the Hague School (Vienna and Madrid, 1996). Mr Feilchenfeldt is a Zürich-based dealer and scholar, with a special interest in provenance research (he helped complete Rewald’s catalogue raisonnée of Cézanne, published late last year). His father worked with the dealer Paul Cassirer, where he was instrumental in exposing the Wacker fraud. Using the gallery’s records, Mr Feilchenfeldt wrote a study on Vincent van Gogh and Cassirer (Van Gogh Museum/Waanders, 1988). Four years ago Dr Dorn and Mr Feilchenfeldt collaborated on an article entitled “Genuine or fake?,” published in Kodera Tsukas’s The Mythology of Vincent van Gogh (Asahi/John Benjamins).

If the provenance dates from the 1890s or earlier, you’re safe

The Dorn/Feilchenfeldt team are now questioning the authenticity of at least 21 pictures in the latest Hulsker catalogue. Their method involves two main lines of inquiry. First of all, provenance. Most of the reasonably convincing Van Gogh fakes did not appear until the early years of the 20th century. It is therefore important to track back ownership, and to be cautious about works without a secure provenance going back to the 1890s. Second, materials, technique and style are ultimately more important in reaching a judgement on authenticity. This requires the traditional skill of connoisseurship, as well as the use of modern scientific methods, such as x-radiography and infra-red reflectography.

Van Gogh’s early Dutch pictures have been less frequently faked than his later French work, mainly because they have never fetched such high prices. But the artist’s Paris period in 1886-88 has offered fakers rich opportunities to introduce unknown pictures. Little documentation survives from Van Gogh’s stay in the French capital, but rumours abound about paintings which he gave away or which were lost.

Still-lifes too pleasing to be by Van Gogh

The Dorn/Feilchenfeldt team are dubious about the authenticity of a series of still-lifes of vases of flowers which Mr Hulsker dates to Paris. Some are simply too “sensuous” for Van Gogh (H1103-4, 1231), including pictures at the Wadsworth Atheneum in Connecticut and Wuppertal’s Von der Heydt Museum. Other flower pictures, including one at the Gemeentemuseum in The Hague, are technically unlike the artist’s work because the paint is mixed on the canvas (H1127-8). A still life of carnations at the Detroit Institute of Arts is on a type of canvas which Van Gogh never used (H1129).

Other doubted Paris pictures include the exuberant Celebration of Bastille Day (H1108), a painting of three pairs of shoes at the Fogg Art Museum in Massachusetts (H1234) and two still-lifes with bread at the Van Gogh Museum (H1121, 1232). Self-portraits at the Gemeentemuseum, the Wadsworth Atheneum, and the Metropolitan Museum are also questioned (H1198, 1299, 1344, 1354).

While working in Arles, Van Gogh sent most of his paintings to Theo in Paris, although some were presented to friends. The fact that fewer were dispersed means that it is more difficult to introduce previously unknown works. But Van Gogh’s Arles period represents the artist’s most highly valued work, so it is still a tempting area for fakers.

The Dorn/Feilchenfeldt team reject Coal barges at the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum in Madrid (H1571), mainly because the topography of the river scene is much less precise than in a similar authentic painting in the Van Gogh Museum. They suggest that Wheatfield with sheaves and mower (H1482), at Stockholm’s National Museum, is a fake based on an authentic picture in the Toledo Museum of Art (catalogued by Mr Hulsker as from Van Gogh’s Arles period, but dated to Auvers by the Toledo museum).

Van Gogh’s year at St-Rémy has offered rather more scope for faking. Partly because of his illness, a considerable number of works were abandoned, while others were given away. Among the works questioned by the Dorn/Feilchenfeldt team are Landscape with Les Alpilles (H1744), Wheatfield with sheaves (H1478), a self-portrait at the National Gallery in Oslo (H1780) and Saint-Paul asylum garden at the Musée d’Orsay (H1840). From Van Gogh’s last weeks at Auvers, Street with two figures (H2110) is rejected, partly because it is executed in a similar style to the Alpilles landscape, with unclear topography.

Eleven drawings are also called into question

Amid all the debate over fake paintings, Van Gogh’s drawings have received scant attention. But an important study of works on paper has just been completed by Dutch scholar Liesbeth Heenk. She served as an assistant curator of the Van Gogh drawings exhibition at the Kröller-Müller Museum in 1990 and is now a specialist at the print department of Christie’s, in London. Dr Heenk’s PhD thesis, deposited this spring at the Courtauld Institute, is the result of the most detailed examination of Van Gogh’s drawings since De la Faille. We are grateful to her for allowing exclusive access to her study.

It is on heavy quality paper, and no other example of this can be found in Van Gogh’s oeuvre. The techniques used and the style are also highly unusual.Dr Liesbeth Heenk

Dr Heenk suggests that 11 works in the new Hulsker catalogue are not authentic. She rejects a watercolour at the Van Gogh Museum, Street scene in Paris (H1187). “It is on heavy quality paper, and no other example of this can be found in Van Gogh’s oeuvre. The techniques used and the style are also highly unusual,” she explained. Despite Mr Hulsker’s acceptance, the work had also been downgraded by the Van Gogh Museum.

Another rejected drawing is Peasant woman peeling potatoes (H790) in the David and Alice van Buuren Museum in Brussels. According to Dr Heenk: “The regular pencil marks betray the typical care of a copyist, and it appears to be based on part of a Van Gogh drawing now in the Kröller-Müller Museum. The lips of the woman have been coloured red, which would have been very unusual for Van Gogh. The brownish woven paper has not been used for other Van Gogh drawings and the signature seems spurious.” Other works which Dr Heenk questions include Sawmill (H136), Man carrying branches (H515), Head of a peasant woman (H747), Houses with two women (H1997) and Path between garden walls (H2078).

Amateur detectives join the fray

Recently two other figures have joined the fakes debate, but both are enthusiasts rather than academic scholars. Ben Landais, a Frenchman based in the Netherlands, caused a major row when he questioned the authenticity of Jardin à Auvers (H2107). He points out that De la Faille recorded that it was once owned by Amédée Schuffenecker, a dealer thought to have handled fake Van Goghs and brother of the artist Emile Schuffenecker. Mr Landais says that the most important evidence for rejecting the picture is stylistic, and on this point he has the backing of Mr Hulsker, who agrees that the painting “does not seem to be by the hand of Vincent.”

Others believe that Jardin à Auvers is authentic. Mr Feilchenfeldt questions De la Faille’s stated provenance, and recently published documentary evidence showing that the painting was sold by Jo Bonger to Cassirer in 1908, and therefore comes from the family collection. He is convinced that it is genuine. Although the picture is also accepted by the Van Gogh Museum, it failed to sell when it came up at Jacques Tajan’s auction in Pais on 10 December 1996. Bidding stopped at FFr32 million and it still belongs to the heirs of Jean-Marc Vernes. Questions about its authenticity must have played some part in its failure to sell.

In an unpublished paper, Mr Landais questions another important Van Gogh, the Metropolitan Museum’s Arlésienne (H1624). He argues that it is not the version of the picture which Van Gogh gave to Madame Ginoux, and must be a fake. The Metropolitan picture formerly belonged to the artist Emile Schuffenecker, and the suggestion is that he could have painted the copy. Mr Landais even questions the ultimate icon, the Sunflowers bought by the Japanese insurance company Yasuda (H1666), and here too the culprits are said to be the Schuffeneckers.

Mr Landais argues that other fakes may well have originated from Dr Paul Gachet, Van Gogh’s friend in Auvers and an amateur artist. Among the works he rejects are the Van Gogh Museum’s Asylum garden (H1850), Cows (H2095) at the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Lille and Daubigny’s garden with black cat (H2105) on loan to Basel’s Kunstmuseum. Mr Hulsker has expressed similar doubts about all the works questioned by Mr Landais (other than the Yasuda Sunflowers, which he accepts). But few other scholars agree with Mr Landais’ arguments, and he admits he is fighting a “crusade” against the established experts.

A campaign is also being waged on the Internet by Antonio de Robertis, a Milan-based Van Gogh enthusiast. He too says he is “at war with the same conspiracy of silence of institutions, critics and collectors, already denounced in 1930 by De la Faille.” Like Mr Landais, he singles out the Yasuda Sunflowers and Daubigny’s garden with black cat as fakes from the Schuffeneckers. Mr de Robertis has also provided The Art Newspaper with a list of 27 other works in the latest Hulsker catalogue which he believes are not authentic, although only two of these are also questioned by Mr Hulsker (H1624, 2107).

Although the Van Gogh Museum is unwilling to discuss pictures in other collections, last month curator Louis van Tilborgh commented on their Asylum garden. He told The Art Newspaper that “Dr Gachet’s artistic talent was limited and he would not have been able to make a painting of this outstanding quality.” Although provenance can help, in the end it is important to look at the work of art. “In our Asylum garden you find the trademarks of Van Gogh’s style: the same length of the brushstrokes, the heavy impasto, and the obvious energy and attention to the painting process.”

The results of The Art Newspaper’s survey reveal that altogether over a hundred Van Gogh works are now being questioned, but with hardly any agreement between the various scholars over which are dubious . In a few cases (primarily works in the Van Gogh Museum which came from Theo’s collection), the works raise issues of attribution. Pictures given to the Van Gogh brothers in the 1880s may have been later mistaken for Vincent’s work. But in most instances the fakes are works which are forgeries, made to deceive.

It is striking that of the forty-five works now doubted by Mr Hulsker, only two are also being publicly questioned by the Dorn/Feilchenfeldt team, Landscape with Les Alpilles (H1744) and the self-portrait in Oslo (H1780).

None of the 11 drawings rejected by Dr Heenk is questioned in the new Hulsker catalogue. This lack of agreement among the experts is strong evidence of the need for a detailed reexamination of Van Gogh’s oeuvre.

The Van Gogh Museum has launched a vast catalogue

The Van Gogh Museum has already taken a step in this direction, by initiating an eight-volume catalogue on its own collection. Vincent van Gogh Drawings 1880-1883, by drawings curator Sjraar van Heugten, was published last year (Van Gogh Museum/V+K/Lund Humphries). This year there will be further volumes on drawings (1883-85) and paintings (1881-85), and the remaining volumes will be out by the end of 2001. The first volume is a model of scholarship and problems of authenticity are being tackled. As former museum director Ronald de Leeuw (now director of the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam) explained “in his forward, questionable works are excluded because “the museum simply cannot lend itself to creating yet more legends around the oeuvre of an artist which is already surrounded by such a forest of myths.”

The other major Van Gogh collection is at the Kröller-Müller Museum in Otterlo, and it too is considering a scholarly catalogue, although this is likely to be some years away. Together the Amsterdam and Otterlo museums hold a third of Van Gogh’s oeuvre, but the majority is scattered in collections around the world. Van Gogh Museum chief curator Louis van Tilborgh and his colleagues have examined many of these works. “Our policy is that we do not normally comment on questions of authenticity, and only then at the request of the owner,” said Mr van Tilborgh. He stresses that the museum is keen on encouraging research, and publishes documentary material in its Cahier series and articles in its annual journal.

Ultimately the fakes will not be weeded out until Van Gogh’s entire oeuvre is systematically reexamined for a new catalogue raisonnée. As director John Leighton points out, “The Van Gogh Museum is the natural focal point for serious scholarly research and any initiative towards a new catalogue raisonnée should begin here in Amsterdam. The detailed catalogues of our collection are the logical first step and when these are complete we will turn out attention to the wider task of a new catalogue raisonnée, involving outside scholars as appropriate.”

Case studies

Gemeentemuseum: a suspiciously pleasing self-portrait

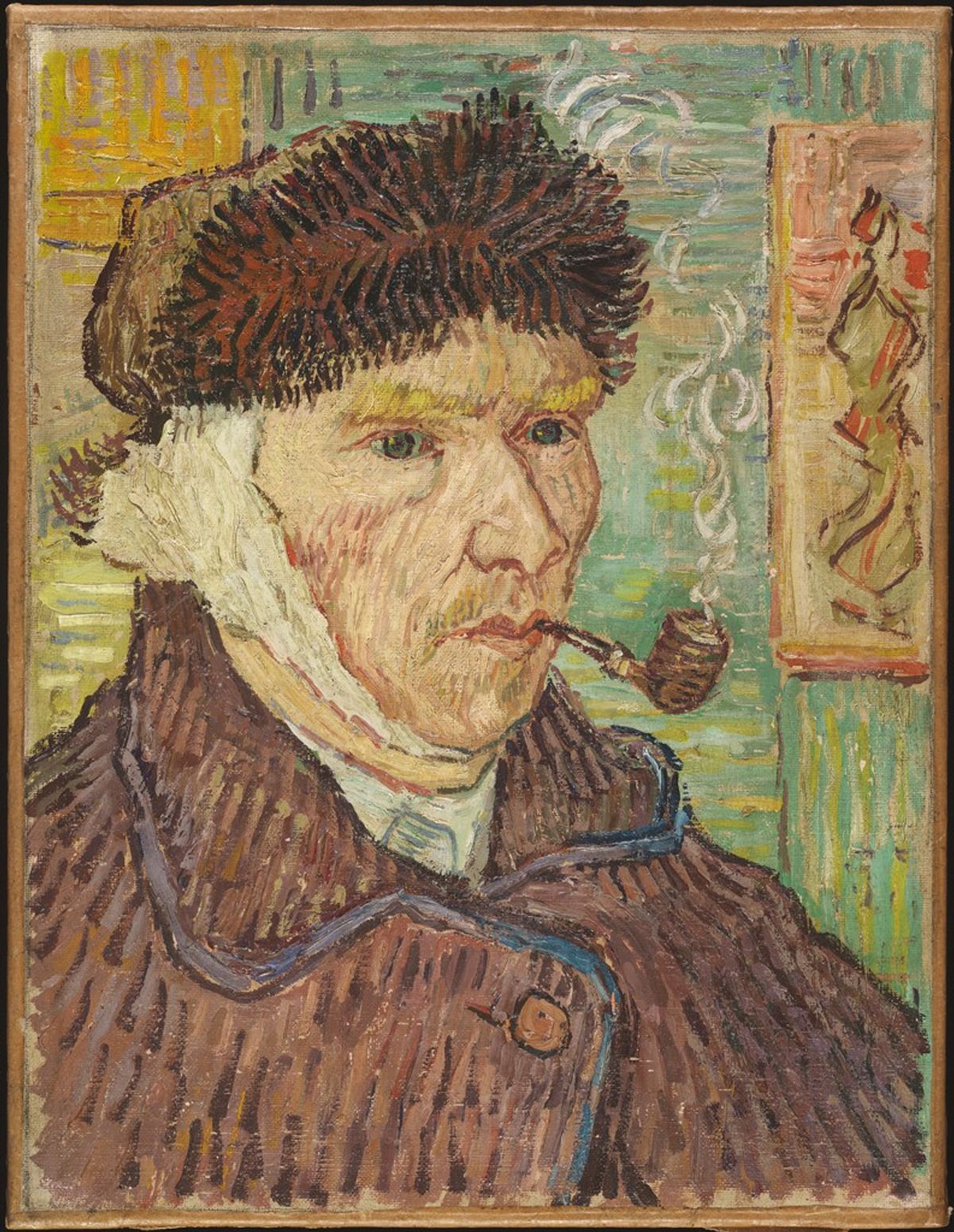

The image we have of Van Gogh, the man, comes from the series of incisive portraits which he painted of himself. His facial features have become so well imprinted on our minds that it is difficult to question the authenticity of a self-portrait. This helps to explain why until recently the self-portraits have not been sufficiently scrutinised by those intent on weeding out the fakes.

The self-portrait at the Gemeentemuseum depicts a rather wistful figure, with a neatly trimmed ginger beard, smartly dressed in a blue jacket and collared shirt (H1198). It is regarded as one of Van Gogh’s early self-portraits, normally dated to 1886, the year of his arrival in Paris. Stylistically, it harks back to his years in the Netherlands and the colouring is typical of the Hague School, with the dark background, the artist’s sober clothes and its relatively realistic flesh tones.

Until recently the authenticity of the Gemeentemuseum’s picture had never been questioned, but the Dorn/Feilchenfeldt team now say it is not by Van Gogh. Dr Dorn points particularly to the ear, which is unduly prominent and scarlet red. “It is quite different from the ears in the other self-portraits. The interior of the ear is just an oval shape, not painted with any detail,” he explained.

Dr Dorn believes it is probably the work of a student. “It is too smooth to be by Van Gogh, and is too sentimental,” he said. The idea that it is by a pupil may come as something of a surprise, since Van Gogh is not generally thought of as a master with students. We tend to think of him toiling away alone and unable to sell his work, and it is difficult to imagine pupils coming to his makeshift studio for lessons.

The clue which alerted Dr Dorn to the idea that the Gemeentemuseum picture might be the work of a student lies on the reverse, where there is a second painting of a still life (H528). This dark and sombre work depicts a tall jar, a bottle, several pots and a small bowl. It has been dated to November 1884, when Van Gogh was living in his parents’ village of Nuenen, and it is one of 13 still-lifes from this period.

Although Van Gogh had taken up oil painting only three years earlier, it was at Nuenen (close to Eindhoven) that he had his first pupils. Early in November 1884 Vincent wrote to his brother Theo: “I now have three people in Eindhoven who want to learn to paint, and I am teaching them how to do still lifes.” A few days later Vincent explained that he was not asking them for money, but hoped to get “tubes of paint.”

Dr Dorn says that one of these three students may have painted the Gemeentemuseum picture. He believes that the pupil might have done the still life, and then turned over the canvas and reused it for a portrait of their teacher. Van Gogh’s first pupil was Antoon Hermans, a goldsmith and antiques dealer who had commissioned him to decorate his dining room. Hermans offered to lend Van Gogh some “old jars” for still life painting, and they probably include some of the objects on the reverse of the Gemeentemuseum picture. Another student was Anton Kerssemakers, a tanner, and he later recalled doing a series of still lifes with “a few jars.” The third pupil was postal worker Willem van de Wakker.

As further evidence that the still life is by a pupil, Dr Dorn points out that exactly the same group of objects depicted from a slightly different angle appear in another picture (H531). He believes that Van Gogh painted this other version, while his pupil sat to his right and did the still life which is now on the reverse of the Gemeentemuseum portrait. Dr Dorn says that it is possible that the student’s still life may then have been touched up by Van Gogh.

Gemeentemuseum curator John Sillevis admits that the Van Gogh picture is “constantly on my mind,” although so far he remains convinced of its authenticity. He points to the provenance. It is believed to have belonged to Vincent’s sister Elisabeth du Quesne-van Gogh, who reproduced it as the frontispiece in the original Dutch edition of her book Personal recollections of Vincent van Gogh, published in 1910. Eight years later the painting was sold to the Gemeentemuseum through the D’Audretsch Art Gallery in The Hague. It appears to have been accepted as a self-portrait by Elisabeth du Quesne and was never questioned by Theo’s widow, Jo Bonger.

Mr Sillevis points out that it was acquired by the Gemeentemuseum’s first director Hendrik van Gelder, who was very careful in his acquisitions: “If there was a shadow of doubt, he would never have bought it. He was making a very serious effort to build up an avant-garde collection.” Mr Sillevis also points out that Vincent’s letters to Theo survive from this period, and it would be curious if Van Gogh had not written about such an important portrait made by a pupil of his.

Stylistically the Gemeentemuseum picture stands up well compared to Van Gogh’s other early Paris self-portraits, which are also painted in the traditional Hague School colouring. Mr Sillevis is not unduly concerned about the slightly clumsily painted ear, having recently closely compared it to self-portraits in the Van Gogh Museum.

Further evidence of the Gemeentemuseum picture’s authenticity is the existence of two sheets of self-portrait drawings in the Van Gogh Museum (H1196-7). Dated to 1886, they depict a similar image and are arguably studies for the oil painting. The drawings would not have been widely known when the Gemeentemuseum picture surfaced.

Overall, the Gemeentemuseum picture is a fine portrait, and it is difficult to believe that a work of this quality was produced by an inexperienced student. The directness of the piercing eyes also suggests a self-portrait, produced with the aid of a mirror.

Mr Sillevis also believes that the still life on the reverse is authentic, comparing it to the dozen similar pictures. He argues that Vincent must have painted the still life in November 1884 and sent the canvas to Theo, who was in Paris. When Van Gogh moved to Paris in 1886 he then reused the canvas, a procedure which he sometimes did to save money.

The painting is one of the highlights of the Gemeentemuseum’s collection, and last year it was shown at Van Gogh exhibitions in Vienna (Bank Austria Kunstforum) and Madrid (Sala de las Alhajas). Although Mr Sillevis remains convinced of its authenticity, he hopes to arrange for the picture to be subjected to a detailed scientific examination.

The Met: a self-portrait with much too random brush strokes

The Metropolitan Museum’s self-portrait (H1354) could hardly be more different from that of the Gemeentemuseum, although just a year separates them. Instead of the neat brushstrokes of the Gemeentemuseum picture, the Metropolitan’s composition is created with whirling strokes and dots of colour, mainly radiating from Van Gogh’s face and encircling his straw hat. The artist has also created a more informal and jaunty image, emphasised by the hat.

Most experts date the Metropolitan picture to late 1887, a few months before Van Gogh’s departure for Arles. By this time he had assimilated the latest developments in Paris, and had seen the work of the Impressionists and their followers. But accurate dating of Van Gogh’s Paris works is difficult, since so few of his letters survive.

Mr Feilchenfeldt first questioned the Metropolitan picture at a symposium at the Van Gogh Museum. Initially, his doubts were raised by its provenance. Vincent gave most of his self-portraits to his brother Theo, and these are recorded in an unpublished family inventory compiled soon after his death in 1891. A few self-portraits were also presented to close friends, such as Gauguin, Charles Laval, Emile Bernard and Dr Paul Gachet. Mr Feilchenfeldt argues that any self-portrait not listed in the 1891 family inventory or known to come from Van Gogh’s friends should be closely examined. Along with the Gemeentemuseum picture, this includes self-portraits at the Wadsworth Atheneum (H1299), Oslo’s National Gallery (H1780), Vienna’s Kunsthistorisches Museum (H1344) and the Metropolitan Museum.

Of these five works, the Metropolitan’s is the most celebrated. Its provenance has been traced back to three dealers: the Charpentier Art Gallery in Paris at an unknown date in the 1920s, the Hans Bammann Art Gallery in Düsseldorf (where it was exhibited in 1928) and Justin K. Thannhauser. To add to the mystery, Bammann once claimed that the picture originally came from an unnamed “Russian collection.”

It was first published by De la Faille in 1927, but it has no secure provenance before that date. This is relatively late for a Van Gogh to surface and the artist’s work was already fetching substantial sums. In the early 1930s the painting was bought by Adelaide Milton de Groot, who offered it on long-term loan to the Metropolitan in 1936. It was bequeathed to the museum on her death in 1967.

Mr Feilchenfeldt also questions the picture on stylistic grounds, arguing there are weak areas. He points particularly to the area just beneath the straw hat “where it is difficult to distinguish between hair and shadow.” The brush strokes in this area appear haphazard and in the picture as a whole “the handling of colour does not match Van Gogh’s work.” Mr Feilchenfeldt believes that it may well have been painted in the mid 1920s as a forgery.

This view is rejected by the Metropolitan’s assistant curator Susan Stein. “The first question is whether it looks right, and I believe that it does. Van Gogh was not aiming at a photographic “likeness”.

“In examining the Metropolitan picture, one has to bear in mind what the artist was setting out to achieve. Most of Van Gogh’s Paris self-portraits were exploratory exercises in colour theory and brushstrokes. In his self-portraits, Van Gogh was experimenting with the juxtaposition of colour. He was making use of the ideas of the Impressionists and Neo-Impressionists, but developing his own brand of pointillist technique.” She points out that the Metropolitan self-portrait has been discussed with colleagues at the Van Gogh Museum, who have dismissed questions about its authenticity.

Like the Gemeentemuseum self-portrait, there is another picture on the reverse: a seated peasant woman peeling potatoes (H654). This has been dated to late February 1885, when Van Gogh was at Nuenen. It is a sombre picture, probably painted by lamplight, and the woman’s profile suggests that it is a study for “The potato eaters.” Writing to Theo, Vincent explained, “I paint not only as long as there is daylight, but even in the evening by the lamp in the cottages, where I can hardly distinguish anything on my palette.”

Mr Feilchenfeldt dismisses the picture of the woman peeling potatoes as a pastiche, describing it as “flat.” Ms Stein disagrees, and argues that “the handling and the restricted palette of dark tones are convincing for the period.”

She says that the double-sided canvas provides further evidence of its authenticity. There are five other double-sided self-portraits in the Van Gogh Museum, which from their provenance we can presume to be authentic. The reverses of these pictures, all with Nuenen scenes, would not have been well known when the Metropolitan picture first surfaced in 1927. De la Faille’s catalogue raisonnée, in which they were described, was not published until the following year, and when some of the Van Gogh family’s double-sided self-portraits were exhibited in the early 1900s it was very unlikely that the reverses would have been shown. How then would a faker have known that there were Nuenen pictures on the backs of the other self-portraits? And why would he have gone to the extra trouble of painting a fake on the reverse?

The picture on the reverse is therefore strong evidence in favour of authenticity. Once again, a full scientific examination of the Metropolitan painting might resolve the question. A provenance that does not stretch back before 1927 does raise doubts. Although this does not unduly concern Ms Stein, she points out that much more research still needs to be done on the early history of Van Gogh works.

Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam: an overly realistic still life

The Dorn/Feilchenfeldt team have already been proved right over one picture, “Still life with bottle of wine, two glasses and a plate with bread and cheese” (H1121). The painting came from the collection of Theo and with this provenance its authenticity had gone unquestioned. The Van Gogh Museum’s 1987 catalogue dates it to soon after the artist’s arrival in Paris, in the spring of 1886.

Four years ago Dr Dorn pointed out that the style seems too realistic for Van Gogh: “the rolls look edible, the red wine drinkable and the silver glistens.” He argued that since the picture came from Theo’s collection, it must have been done by a friend of the two brothers. Important evidence for his theory is that after Theo’s death in 1891 the painting was not listed in the unpublished inventory of works by Van Gogh. Presumably years later Jo Bonger assumed the still life was by Vincent and it was then wrongly attributed.

Modern scientific techniques have now confirmed Dr Dorn’s doubts. Three years ago the picture was x-rayed, revealing the image of a woman was underneath, at right angles to the still life (in the x-ray, the plate is just next to the woman’s face). The hidden picture appears to be a conventional head-and-shoulders portrait, and as Van Gogh Museum curator Mr Van Heugten now admits, it has “little in common” with Van Gogh.

This discovery was made during a project to x-ray 130 oil paintings in the Van Gogh Museum. No fewer than twenty canvases were found to have been reused, with earlier images underneath. But this still life was the only case where an x-ray examination led to a work being downgraded as a Van Gogh.

The canvas of the woman’s portrait had been scraped before the still life was started, making it difficult to examine the technique of the original picture. But in the x-ray, some brushstrokes are visible in the woman’s garment. “Though the artist was apparently working rapidly, one cannot help but notice a certain dullness: the strokes lack both the strength and structure of Vincent,” admitted Mr Van Heugten.

Mr Van Heugten says that “from a stylistic point of view it is indeed difficult to situate the canvas in Vincent’s oeuvre.” He explained: “Only the handling of the bread is somewhat reminiscent of his free brush work, whereas the rest is distinguished by a manner that is reserved, if not lacklustre. There is nothing of interest in the background, while the glasses, plate and knife are arranged against them with no more than technical competence.” He concludes that as another artist was responsible for the hidden portrait, this appears to confirm that the still life is not by Van Gogh and it should be attributed to an anonymous artist. The painting has now been removed to the vaults.

Who then was the artist? He was probably a friend of one or both of the Van Gogh brothers, and the still life may well have been a gift or have been exchanged for a work by Vincent. The style has similarities with that of Van Gogh, so this suggests that the painter must have been a close colleague in Paris. Dr Dorn is now trying to identify the artist. He believes that it was a reasonably prominent French painter, and he hopes to publish his theory shortly.

Now that “Still life with bottle of wine, two glasses and a plate with bread and cheese” is no longer considered to be by Van Gogh, questions must be asked about a similar work, “A plate with rolls” (H1232). This other still life, normally dated to early 1887, also comes from Theo’s collection and is at the Van Gogh Museum. It is accepted by Mr Hulsker and is in the museum’s 1987 catalogue. In this second still life, the plate appears to be the same as in the downgraded work and the bread and rolls are painted in a similar style . The same artist is therefore likely to have been responsible for them both.

Musée D’Orsay: “St Paul’s Asylum garden”, too summary to be by Van Gogh

The Musée d’Orsay’s “Saint-Paul Asylum garden” (H1840) is dated to October 1889, when Van Gogh was in St-Rémy. The artist is assumed to have painted it for the asylum’s director, Dr Théophile Peyron, who is likely to be the smartly dressed man standing proprietorially next to the old pine tree. Writing to his brother Theo on 2 November 1889, Vincent reported that he had “done a canvas for M. Peyron, a view of the house with a large pine.” The Musée d’Orsay picture depicts the garden entrance of the asylum, and the figure in the yellow straw hat coming through the doorway may well represent the artist. Van Gogh frequently painted in the asylum garden and it was where he spent much of his time when his health was reasonably good.

The 1970 edition of the De la Faille catalogue records “Saint-Paul Asylum garden” was given by Dr Peyron’s son Joseph to Marie Gasquet, the wife of a St-Rémy poet. She in turn is said to have sold it to the Bernheim-Jeune gallery in Paris. But this early provenance is undocumented, and the only firm evidence is that Bernheim-Jeune sold it to Cassirer in 1914.

The St-Rémy painting then passed through several hands and in 1973 it was given by Parisian dealer Max Kaganovich and his wife Rosy to the Jeu de Paume in Paris (and transferred to the Musée d’Orsay in 1986). Dr Anne Distel, chief curator at the Musée d’Orsay, admits that because the picture arrived as a gift, the museum did not subject its provenance to detailed scrutiny and the details given in the De la Faille catalogue were accepted.

But Dr Dorn is dubious about the provenance. “The link with Peyron is uncertain and Madame Gasquet was a questionable figure. The established provenance only goes back to 1914,” he explained. Dr Dorn speculates that the story about Peyron could well have been produced to explain the picture’s late appearance. The existence of Van Gogh’s letter of 2 November 1889 would have provided a faker with a suitable subject.

To add to the mystery, there is another authentic painting which depicts a similar view of the asylum entrance and garden. “Pine trees in the asylum garden” (H1799), now in the Armand Hammer Collection in Los Angeles, was painted from a point slightly further away from the building and shows a clump of tall pine trees and a large expanse of sky. This work is dated to early October 1889, a month before the Musée d’Orsay picture. Those who doubt the authenticity of the Musée d’Orsay work suggest that a faker could have based his picture on the Hammer painting. But Van Gogh frequently did different versions of the same subject, so the existence of the variants is not surprising. An opportunity to compare the two paintings side-by-side might be revealing.

Dr Dorn also questions the authenticity of the Musée d’Orsay picture on other grounds. He believes “the very summary treatment of the architecture” is unusual in Van Gogh’s oeuvre. Dr Dorn is concerned about the technical details in the handling of the paint, which he says is unlike that of the artist, particularly the “dry application” of the paint and the unprimed twill canvas.

Dr Distel has an open attitude towards Saint-Paul Asylum garden. “At present it is accepted as authentic, but we are quite willing to look at any new evidence which emerges,” she told The Art Newspaper. We can reveal that the Musée d’Orsay is now subjecting the painting to detailed scrutiny, following suggestions from Dr Dorn and other experts. X-rays and infra-red reflectograms will be taken. These investigations are expected to be completed shortly.

Real discoveries

Everyone’s dream is to discover an unknown Van Gogh, but very few are lucky. According to former Van Gogh Museum director Mr de Leeuw, “We receive a constant stream of queries regarding the authenticity of works. For staff this is very time-consuming, and it is only very rarely that their work does not end in disappointment.”

But it does happen, and works do emerge. In May this year a drawing of a woman was found in the Netherlands. The sketch had remained in private hands and had never been published. It came up for sale at Christie’s Amsterdam on 4 June and sold for DFl.231,000 (£73,000), four times more than the estimate.

The Art Newspaper has compiled a comprehensive list of a dozen works which have been widely accepted as authentic since the 1980s, although in some cases not all the experts agree. We have excluded a number of drawings at the Van Gogh Museum which were not published in the De la Faille and Hulsker catalogues, but which have been reproduced in the museum’s own catalogue or in Johannes van der Wolk’s study of the sketchbooks (although relatively unknown until recently, these works came from Theo’s collection and cannot be regarded as discoveries).

Portrait of a woman: This pencil drawing has been authenticated by Van Gogh Museum curator Mr Van Heugten. Dating from the spring of 1882, it is similar to a slightly smaller work now in a South American collection (H352). Both drawings depict Sien, the former prostitute the artist was living with in The Hague, or possibly her mother. The newly-discovered version was found early this century by critic Hendricus Bremmer, who recommended it to the wealthy collector Hélène Kröller-Müller. She gave it to her daughter and the drawing was later given to the present Dutch owner as a wedding gift in the 1940s. Christie’s sold the work on 4 June.

Windy landscape with a woman and child: Rejected by De la Faille in 1930, this drawing was long dismissed as a fake, but last year it was accepted by the Van Gogh Museum. The pencil drawing, touched up with ink, is on brownish-pink watermarked paper which is similar to three authentic works. Curator Mr Van Heugten dates it to April-May 1883, when Van Gogh was in The Hague. The work was in a German private collection and was bought by Hamburg dealer Thomas le Claire in 1994. On 2 December 1996 it sold at Christie’s for £155,500.

Still life with flowers: Discovered in Switzerland, this bouquet with asters was brought to Mr Feilchenfeldt’s Zürich gallery and in 1995 it was authenticated by the Van Gogh Museum. Although it is prominently signed Vincent in red paint, it had been purchased in a flea market in France after World War II and was later consigned to an attic. The oil painting is now dated to the autumn of 1886, when Van Gogh was in Paris. The picture had never been restored, which is extremely unusual for a Van Gogh. It is still in a private collection.

Man in a snow-covered landscape: This watercolour, also made with pencil and ink, is a copy of a lithograph of a work by Josef Israëls, entitled “Winter.” Van Gogh’s own reproduction of the print survives in one of his scrapbooks. Signed Vincent, his watercolour copy probably dates from his stay in Amsterdam in mid 1877, when he was preparing to study theology. The watercolour was acquired in a Dutch provincial sale by the Bockweg Gallery in Epe. Museum curator Mr Van Heugten describes the Van Gogh attribution as “fairly secure.”

Vase with flowers: The Paris still life appeared in Milwaukee in 1990. It was said to have been bought by a Zürich banker between 1910 and 1930 and later inherited by an American couple. The oil painting was authenticated by the Van Gogh Museum, which concluded that the typical brushstrokes, colouring and composition were similar to still lifes from the summer of 1886, when the artist was in Paris. The signature, a simple “Vt,” occurs on only one other Van Gogh painting. In March 1991 the picture was sold in Chicago by Leslie Hindman Auctioneers, fetching $750,000.

Landscape with trees: The watercolour was first exhibited in 1990 at the exhibition of Van Gogh drawings at the Kröller-Müller Museum. Curator Mr Van der Wolk dated it to September 1883, when Van Gogh was in Drenthe. The paper has the same watermark as another authenticated work. It had originally been acquired by the Rotterdam dealer Oldenzeel, who bought work left behind at Van Gogh’s studio in Nuenen, and was auctioned in 1904. It is now in a private collection.

Bowl with daffodils: In a private collection since the 1920s, this still-life was not published until 1988. Ronald Pickvance dated the picture to April 1885 in Nuenen, although it could also come from Van Gogh’s period in Paris the following spring. X-rays have revealed that there was an earlier landscape underneath. Unusually, the oil painting is on cardboard. After being displayed at the Van Gogh Museum, it is back in private hands.

Cottage: This oil painting is dated to Nuenen, June-July 1885. Newly discovered, it was auctioned by Sotheby’s in 1988, selling for £83,600. On 22 March last year it was sold at Drouot (Laurin-Guilloux-Buffetaud) at the request of L’Administration des Douanes. It is now in a Dutch collection.

Peasant kneeling in front of a hut: This watercolour is dated to September 1883, when Van Gogh was in Drenthe. It was in several Dutch private collections and remained unpublished. It sold at Christie’s in 1986 for £41,000 and its authenticity is accepted by Dr Heenk.

Peasant and studies of pitchforks: The charcoal drawing dates from Van Gogh’s stay in Nuenen in 1885. On the reverse is another sketch of a peasant man. The work first appeared at Sotheby’s in 1984, when it sold for £16,500.

Olive trees at Montmajour: The fine ink drawing was done by Van Gogh in July 1888 at Montmajour, the ruined abbey just outside Arles. It was left to the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Tournai by Belgian collector Henri van Cutsem in 1925, but it was uncatalogued and not recognised by museum curators as a Van Gogh until 1957. It remained unknown to most Van Gogh scholars until 1984, when it was exhibited by Ronald Pickvance in his “Van Gogh in Arles” show at the Metropolitan Museum.

Man, standing with arms folded: The pencil drawing was first published in 1983 by Martha Op de Coul, who dated it to March-April 1882. It is a sketch for a figure in the drawing “Fishdrying barn” (H152), from May 1882, Scheveningen, the port outside The Hague. It is in a private collection.

People strolling in a park: The oil painting is dated to Paris, in the autumn of 1886. It was first exhibited in Bogomila Welsh-Ovcharov’s exhibition, “Vincent van Gogh and the birth of Cloisonnism,” held in Toronto and Amsterdam in 1981. The picture, previously unrecorded, came from the heirs of art critic Albert Aurier and is now in a private collection.