As the US economy stumbles back to its feet, arts sponsorship persists, but it is increasingly associated with marketing concerns rather than disinterested corporate philanthropy. Thus, while overall US corporate support for the arts has declined from a 1985 high of $700 million to something around $500 million today (about 17% to museums), arts spending by corporate marketing departments has climbed from $100 million in 1988 to $245 million in 1993, and is projected to continue to rise. On the one hand, marketing dollars replenish philanthropic resources channelled towards more proactive expressions of good corporate citizenship, especially education and crisis causes. But on the other hand, this money has to be accounted for in business terms.

A 1993 survey found that 62% of businesses would like a greater return on their arts investments, and many desire more visibility than arts organisations are willing to provide. “The evolution is away from pure donations to a true business-to-business partnership”, says Judith Jedlicka, director of Business Committee for the Arts, an organisation that encourages business-giving to the arts. Alice S. Zimet, vice president for Cultural Affairs at the Chase Manhattan bank, affirms, “We’re talking about marketing dollars that would otherwise go to promoting products and services. So the key is to do something beneficial not only for the arts organisations, but that also adds value for the bank and its customers. They used to perceive us as vultures in pinstripe suits”, she laughs, but now, with soaring exhibition costs and competition hotter for corporate largesse, museums are willing to sit down and talk.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art annually spends $6-8 million for exhibitions, and has to raise 70-90%, with corporations providing about two-thirds. Emily K. Rafferty, head of development at the museum, recognises that “corporations are not in a position simply to part with $2 million at the door and walk away. They have a responsibility to maximise their dollar, and it’s our job to make sure it’s done in a tasteful way that does not compromise the institution, and meets at least some of the marketing objectives of the corporations”.

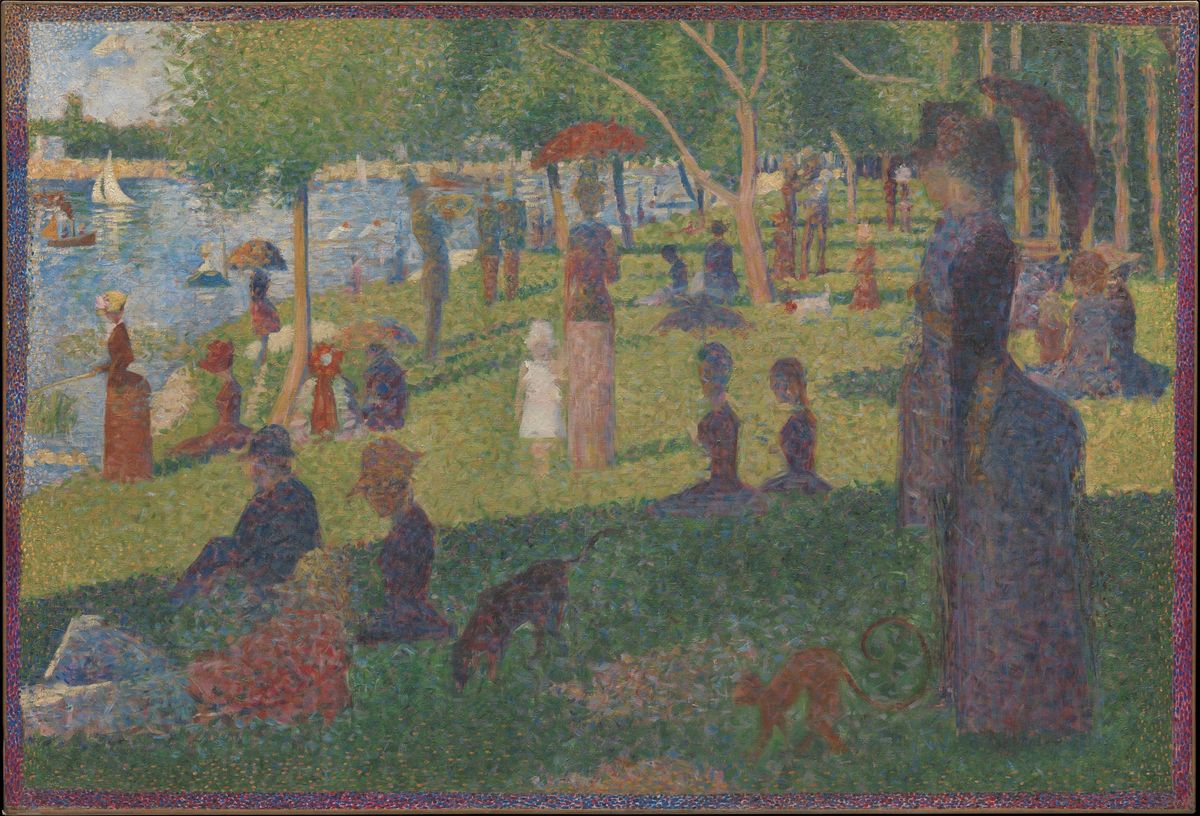

Corporations often claim they want merely to be good citizens, improving the quality of life in the communities in which they do business, yet few are willing to give grants for unrestricted purposes. Like Polaroid and Kodak, who support photo shows related to their products, most prefer a project on which to hang the company name. For example, for its entry onto the New York Stock Exchange, Elf-Aquitaine sponsored Seurat at the Met; seeking co-operation for its oil interests in New Zealand, Mobil Corporation funded a US tour of Maori art; to amplify its advertising slogan, “Bullish on America”, Merrill Lynch sponsored a national tour of cowboy painter Frederic Remington; and to underline subtly its image as an all-American provider of transportation, Ford Motor Company is backing a touring show about horse culture in the West.

Certain companies seem ever more intent on shaping the programmes they fund. For example, museums have bent over backwards to qualify for “AT&T: New Art/New Visions”, which favours work by “living artists of colour, especially women”. Tim McClimon, former vice president for Arts and Culture at AT&T Foundation, explains: “For years AT&T was a white male bastion, but today we have a very diverse work force: over 50% are women, and many are from various ethnic groups. This programme reflects our employee base and our customers, worldwide”. To get their piece of the diversity pie, “museums are pandering to foundations’ desires”, asserts a development officer at a midwestern museum, who wishes to remain anonymous. “The education departments have become the whores of the museum world”, she says, “inventing schemes to satisfy grant requirements based not on the content or scholarship of a show, but on how it involves the community”.

“An aura of political correctness hovers over European-themed exhibitions”, observes Peter Sutton, head of Old Master Paintings at Christie’s NY. In his former position as curator of European Paintings at the MFA, Boston, he faced enormous difficulty raising money: “Try selling Flemish painting as a form of community outreach”, he sighs, referring to his blockbuster, The Age of Rubens. To pay for the show, the museum exported a still-life survey to three sites in Japan, which took in $1.5 million in fees. Regarding the tendency of philanthropies to fund social programmes to the exclusion of the arts—which are deemed a luxury—Mr Sutton declares: “It’s a failure of museums to get their messages across. Visual literacy is something we need in an age of instant reproduction”.

While the cost of exhibitions goes on rising, the size of sponsorship keeps going down. “Throughout the 1980s, a single company would sponsor a major exhibition for around $800,000”, says Tom Jacobson, head of grants and sponsorship at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. “Now we are working on smaller sponsorships, and working harder to get them”. Even the National Gallery of Art reports that the average primary grant has fallen to $5-600,000. Smaller museums need to raise smaller sums, but they too are forming consortiums of sponsors who share the credit. Several museums report that companies are once again considering larger budgets, and the field is opening up internationally, with American companies sponsoring overseas tours and foreign corporations underwriting North American shows. “The history of good corporate citizenship in this country is the global message that’s gone out”, says Elizabeth Perry, head of Corporate Relations at the National Gallery, “and that’s the message that our European and Asian counterparts have gotten”.