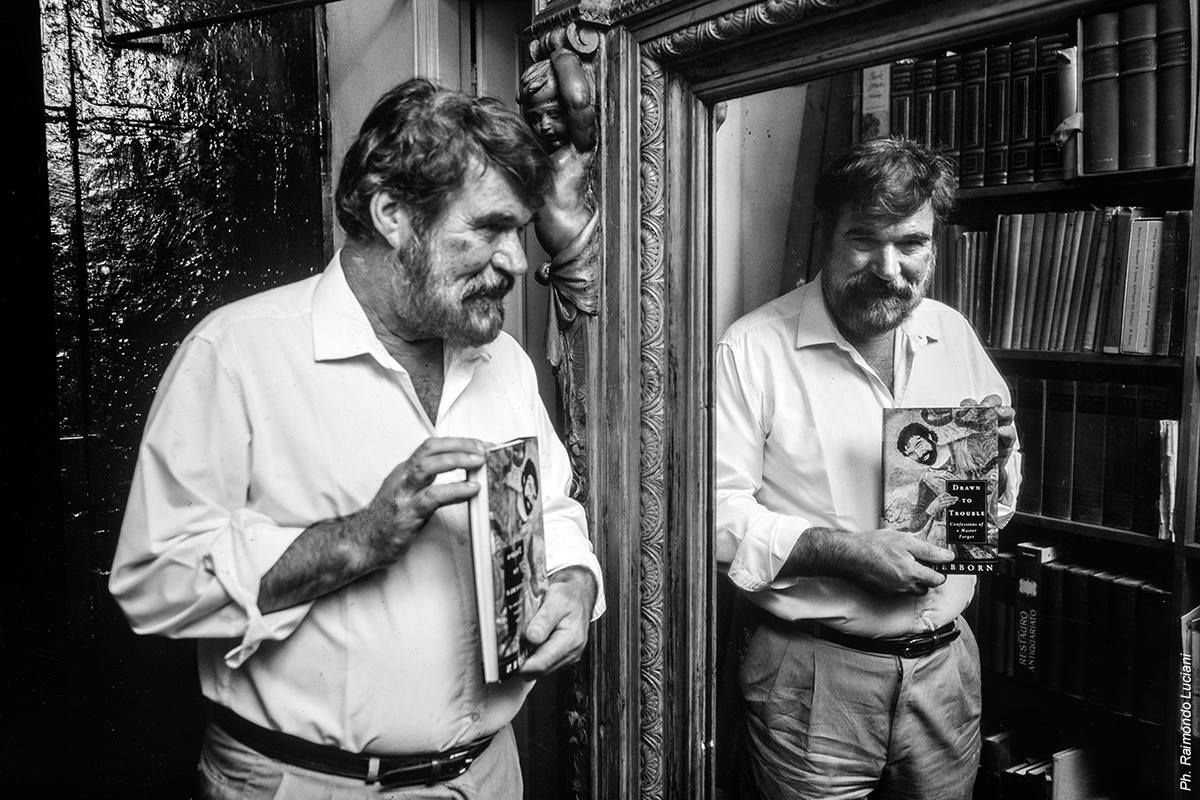

In Drawn to Trouble: The Forging of an Artist, Eric Hebborn relates his autobiography as a forger. By his own admission his career was briefly successful in the 1970s and was abruptly interrupted (everywhere except in Italy where he seems to have continued to find a ready market for his products) by Geraldine Norman’s exposé in The Times in 1978. While the trade has known about him for years, the general public, to whom Hebborn addresses this book, may not have. Disclaiming ad nauseam any moral responsibility for launching his creations via Colnaghi’s, Sotheby’s and Christie’s, Hebborn asserts that he merely presented the experts with drawings, allowing them to put on the attributions and market them. On p. 211 of his book he lists his “unwritten moral code” which includes: “never to sell to a person who was not a recognised expert, or acting on expert advice”....

”Never make a description or attribution unless a recognised expert had been consulted; in which case the description or attribution would in reality be that expert’s and not mine”.

By his own claim, his forged oeuvre numbers some 1,100 works ranging from “Mantegna” and “Giorgione” to “Van Dyck” and “Piranesi” and finally to “Augustus John”.

Dealers are depicted as charlatans who are intent only on large profits and fail to detect obvious errors of the wrong type or ink or period/make of paper. It is therefore their responsibility that the drawings were then passed allegedly onto unsuspecting buyers. Yet Hebburn admits to selling both “right” and “wrong” drawings; was he not therefore functioning as a dealer himself and confusing potential buyers by offering a mix? Christopher White, now the director of the Ashmolean Museum, then at Colnaghi’s, and Yvonne Tan Bunzl, the drawings dealer, both recall buying a drawing from him whose authenticity is not disputed. Further, Christie’s catalogues from the early 1970s show Hebborn as a buyer of drawings at auction.

As for the not so small matter of money, he describes his living in comfort in Italy with cook and cleaner and he admits at times to a dealer paying him partly for a work and then sharing in the subsequent profits. Who then is the exploited and who the exploiter?

First let us take the moral responsibility issue. By his own admission, Hebborn created false collectors’ stamps, fictitious provenances, aged paper and damaged drawings to look old. He carefully studied artists’ oeuvres to create drawings which related to generally accepted works. He claims on two occasions (for drawings by Sandby and Jan Breughel the Elder) to have copied the original drawings and replaced them with copies in the original frames on which old dealer labels were already affixed (the original Breughel he claims to have then flushed down the lavatory!).

Indeed Hebborn’s unmasking came about when Konrad Oberhuber (not as spelled in the book “Conrad Oberhuver”), then research curator at the National Gallery in Washington, DC (now director of the Albertina in Vienna) saw several drawings in London after having bought earlier a “Cossa” drawing from Calmann (not Colnaghi’s, as stated in the book). After having visited Richard Day and seen a doubtful drawing (which turned out not to be by Hebborn) and discussed that quite a few fakes were around, he visited Calmann and was shown a Raphael which was clearly a fake; Calmann then invited him home where he showed him a drawing by Ercole de Roberti (who, like Cossa, does not have an easily recognisable corpus of drawings attributable to him). Oberhuber told The Art Newspaper that he then realised it was the same hand as the Cossa (and a Sperandio that he had earlier purchased from Calmann). Later, discussing them with Christopher White, he recognised that the same hand had also executed the drawing White had earlier sold to the Morgan library: the source was Hebborn. Oberhuber said that they were able to return the Cossa to Calmann, but not the Sperandio, since it was on the correct paper. Common to these drawings, notes Oberhuber, were many strange and curious attributions on their backs, or drawings connected to another work; he began to feel that they had been made for the art historian’s consumption.

Unfortunately, several of the key participants are no longer with us (Hans Calmann, Philip Pouncey and Anthony Blunt) and therefore cannot offer their version of events. Some of Hebburn’s accounts defy logic in addition to being at variance with the memories of still living participants. Take the case of the “Francesco del Cossa” “Pageboy with lance”, inspired by a British Museum drawing. Hebborn claims that Philip Pouncey at Sotheby’s fully attributed the drawing to Cossa, based on the British Museum drawing which was only catalogued as “attributed to.” This defies any rational art historical procedure and Pouncey was, after all, both a scholar and a brilliant connoisseur. He simply would not have upgraded a work based on the questionable attribution of another work. The drawings dealer Richard Day, who was with Pouncey at Sotheby’s then, recalls distinctly Pouncey’s disappointment with, and worry about, the drawing consigned by Hebborn. It subsequently appeared at Sotheby’s sale of 20 April 1967 catalogued as “attributed to” (not, as Hebborn claims, as an unequivocal “Cossa”). The drawing was then sold to Colnaghi’s and on to the Pierpont Morgan library. Hebborn fails to acknowledge that Colnaghi’s even more cautiously catalogued the work as “North Italian School, fifteenth century.”

Hebborn also claims (p. 260) that he made the collectors’ marks (Reynolds’s and Richardson’s) on the drawing in watercolour, which should have tipped off the experts. Richard Day says categorically that they were clearly stamped in ink and later proven only marginally inaccurate in size; he recalls that Pouncey even then was slightly sceptical of them, but was not absolutely certain of his doubts. Yvonne Tan Bunzl later examined the marks at the Pierpont Morgan library and supports their being stamped; the slight bleeding of the ink into the paper evident in microphotographs was at odds with authentic collectors’ marks on other drawings.

To proceed to other inaccuracies, Hebborn wrongly states in a caption below fig.91 that “Stefano della Bella” ‘A huntsman’, 1972, pen and wash, sold to Colnaghi’s, [was] subsequently bought by Tan Bunzl and sold to the National Gallery of Canada”. In fact Tan Bunzl neither bought this drawing nor sold it to that museum. She states that she did handle the subsequently illustrated drawing by della Bella, A young boy teaching his dog to beg, on behalf of a private collector who had purchased it from Colnaghi’s; it was this drawing that the National Gallery of Canada bought. When she learned that it was a Hebborn, Tan Bunzl offered to take back the drawing, but the museum decided not to take up her offer.

The Bernardo Castello, An angel assisting in the battle against the Turks that Hebborn claims he faked and that Tan Bunzl purchased from him in Italy in 1972 was actually sold at Sotheby’s in January 1966 and was purchased by Colnaghi; Colnaghi sold it to Hebborn a few months before Tan Bunzl bought the drawing from him. Given that he had purchased original drawings from Christie’s and Colnaghi’s, one therefore wonders whether all the drawings he lists on pp. 342-43 as having consigned to Christie’s Louisa Vertova in 1974 were original Hebborns; could not some real Old Masters have been mixed in with the “new Old Masters”?

This also raises doubts over his claims that the Piranesi drawing he smuggled out of Italy and sold to Hans Calmann, who then sold it to the Ny Carlsberg Foundation (not, as the caption reads in the book, to the National Gallery of Denmark), which in turn gave it to the Royal Fine Arts Museum in Copenhagen, was a Hebborn and not a Piranesi. According to the current curator of the Prints and Drawings department, Carl Fischer, the museum paid £16,000 (not £14,000 as Hebborn states) for the drawing. When Norman’s 1978 article appeared, the then curator Erik Fischer broke the customary ban on loans longer than three months to allow the drawing to be exhibited in Washington and at the Fondazione Cini in Venice, to scholarly acclaim. In my opinion this is one of Hebborn’s more doubtful claims since the drawing is the most complex compositionally, as well as intricate artistically, of any reproduced in the book (including the two other, much less ambitious “Piranesi” studies illustrated which have a more conveniently cropped composition with limited view). Hebborn seems most at home with a sparsely figured composition with minimal references to setting. Yet Oberhuber remains convinced that it is a Hebborn on the basis of calligraphic similarities with other of Hebborn’s drawings.

Ironically, the controversy about the drawing inspired Chris Fischer (who is convinced of its authenticity) to mount an exhibition centred on the drawing, which was remarkably well attended; with humour, he observes that Hebborn has succeeded in making his department famous.

Among all those remaining who were, so briefly, taken in by Hebborn, there seems agreement that he has now produced little more evidence of his activity than the forty or so forgeries known since 1978. Where are the 1,000 plus that he claims to have executed? They could be circulating in Italy, which has a market notoriously indifferent to dubious works. Yet it would seem that the Italians are fully aware of his existence. One Milan dealer commented, “Oh yes, we’ve known about him a long time. His works are easily recognizable; he makes drawings to order. His fakes started off well done and careful, and then he began using the wrong paper and so forth.” The highly respected independent scholar Federico Zeri in La Stampa exclaimed: “Oh, is that what he is called? I haven’t had the pleasure of meeting him, but I know his work well. He has done thousands of them; very good examples. He is very good, our chap, at cornering the supplies of right paper. How amusing that he lives near me!” In closing the chapter on Hebborn, one London dealer mused, “Why didn’t Hebborn stick to Hebborns? He’s rather good. I wouldn’t mind owning one of his own”.

Maybe there is still time for him to go straight.