“Imagine performing a frontal lobotomy”, asks Samir al-Khalil in The Monument: art, vulgarity and responsibility in Iraq, published this month, “on an otherwise normal brain, with a view to permanently eradicating the ‘artistic’ component within, and you have some idea of the remarkable accomplishment of Saddam Hussein with respect to modern Iraqi culture”. It must be admitted that the health or even survival of modern Iraqi culture does not at present appear to be among the Western world’s highest priorities, and an analysis of Saddam’s recent artistic strategy in Baghdad — manifested principally through the erection of series of buildings and monuments evidently capable of offending the aesthetic sensibilities of outside observers — is scarcely the stuff of CNN News. But al-Khalil’s impassioned if painfully overwrought book does deserve at least some of the attention it so urgently claims, for at one level it is an attempt to present the modern public art of Baghdad as a key to understanding what few in the West feel they have yet been able to grasp – the true psyche of Saddam himself. The book also reveals, albeit less willingly, that art and visual imagery (much of it produced with the help of Western finance and technical help) are perhaps the most potent and successful weapons in the arsenal of rhetoric which has fostered and sustained the astonishing degree of popular support enjoyed by Saddam Hussein throughout the Arab world.

Among the army of unwitting suppliers to that arsenal was, improbably enough, the Morris Singer Foundry in Basingstoke, England. In the late 1980s it provided Saddam with the giant-size enlarged casts of the President’s forearms which form part of Baghdad’s striking Victory Arch, the focus and methodological axis of al-Khalil’s study. The arch was commissioned by Saddam Hussein in 1985 to celebrate his expected victory in the war with Iran, whose end was then scarcely in sight. It was completed and formally opened in August 1989 (Saddam Hussein, televised across Islam, rode under the arch on a white Arab charger), a year after peace had been concluded and victory claimed by each side. The monument is loaded with the symbolism and indeed the hardware of war: the swords represent the Arab-Moslem defeat of the non-Islamic Persian Sassanian empire at Qadisiyya in 637 (a defeat Saddam Hussein claimed to be re-administering) and were made with 48 tons of steel from melted-down tanks and weapons from the modern Iran-Iraq campaign. At the base of each forearm, meanwhile, is a giant net containing 2,500 helmets taken from Iranian prisoners of war.

Bizarre, poignant, and in al-Khalil’s view crashingly vulgar, if the Victory Arch survives Allied cruise missiles it will endure as a revealing testimony to the personality, self-image and ambition of its patron. It is this potential permanence which seems most to offend al-Khalil, an ex-patriot Iraqi and amateur art historian whose fervent rejection of the monument’s artistic quality and integrity is deeply and unapologetically bound up with his condemnation of Iraq’s political rgime. Central to his theme is his belief in a moral obligation to despise all art produced at the bidding of evil men. Above all, he urges that we deny the monument’s claim to be a work of art at all, and he lambasts the likes of Andy Warhol and Robert Venturi for throwing calculated doubt on the proper distinction between art and “kitsch” and allowing potentially subversive essays in the latter to masquerade as the former: “Pop art hasn’t made dictators possible but it has helped to make them credible”.

This intriguing if incautiously over-worked proposition implicitly places the products of Saddam Hussein’s artistic programme (a decade’s worth of new public architecture and sculpture in the context of a new city plan for Baghdad) on a quite different level to those of political despots from Roman emperors to Renaissance princes, from Napoleon to Ceausescu. In essence, no such distinction exists. Saddam Hussein’s Victory Arch is his Arc de Triomphe, and it is no more nor less conceptually abhorrent than, say, Napoleon’s column in the Place Vendôme made from the bronze of 1,200 cannons captured at the battle of Austerlitz. Urban monuments, be they to victory, peace or personalities, serve to enshrine a relationship between their subject and their locality just as surely as a Roman Triumph, and Saddam Hussein’s precarious orchestration of and hold over Iraq’s disparate ethnic and intellectual factions depends as much on the symbolic and visual grasp he places on its capital as on any of his military manoeuvres outside it. Most pertinently, Baghdad has been bidding through its reconstructed public image for recognition as the rightful centre of the Arab world — a new Rome for a holy empire ranged against the infidel economic power of the West. The Qadisiyya swords of the Victory Arch are those of jihad — ill-suited to the battle against Moslem neighbours Iran to which they initially referred, but chillingly fitted to the wider campaign they seek to inspire. Past and present street demonstrations in support of Saddam Hussein in cities far beyond Iraq attest to the popularity and propagandist skills of one of the strongest pretenders to pan-Arab leadership this century.

Beside such issues, al-Khalil’s lengthy and subjective diversions on the meaning and mis-use of “kitsch” (a term he never successfully defines), and on the rise and alleged fall of Iraqi art, are sometimes tiresome and weaken the basic and real strengths of his project. For the book’s importance lies in its revelation of how Saddam Hussein has grafted on to the aspirations, emblems and traditions of Islamic culture his own persona and political agenda.

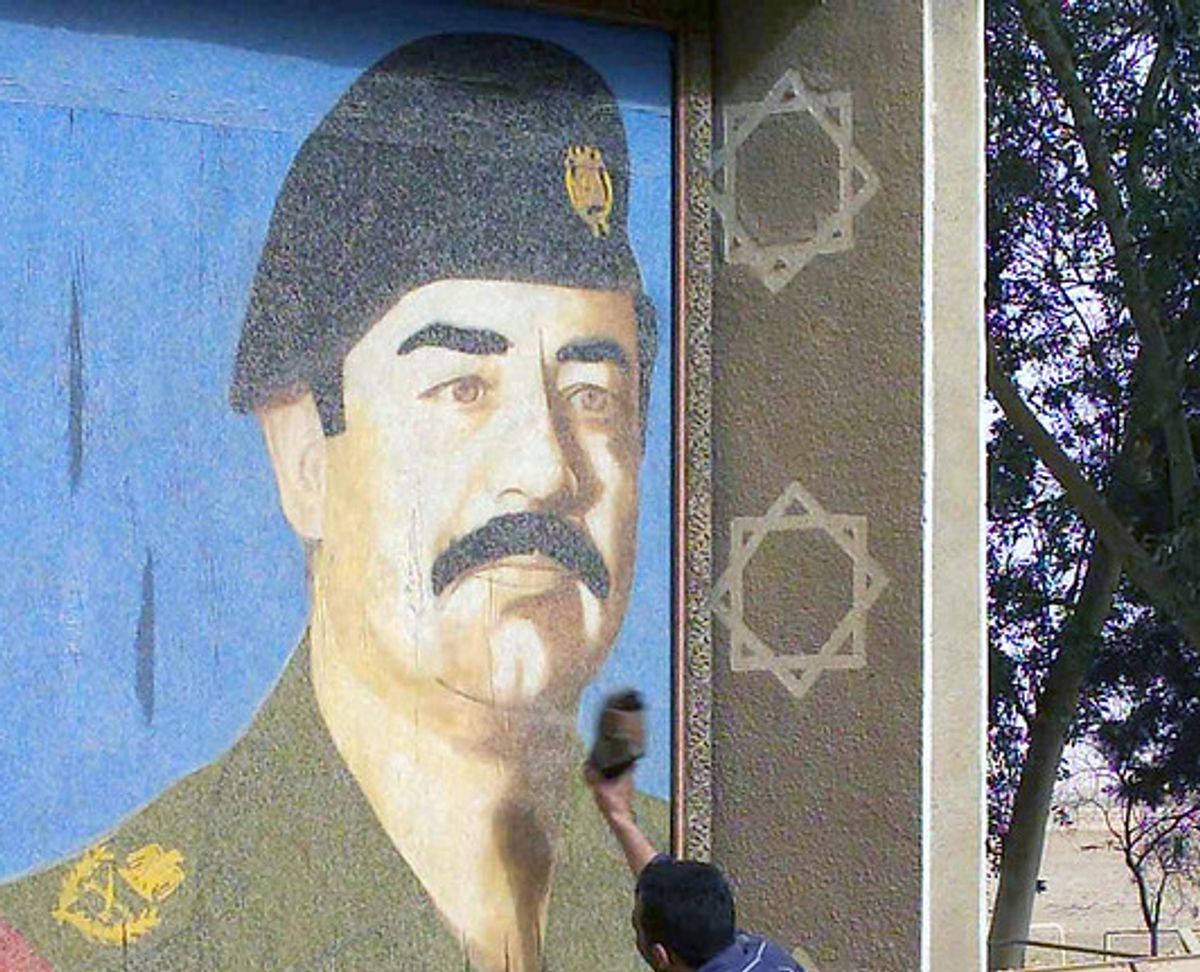

This he has done with varying degrees of subtlety but always with efficiency. His recent re-construction of the equestrian monument to King Faisal, for example, torn down in 1958 in the coup which paved the way for the Ba’athi ascendancy and Saddam Hussein’s eventual presidency, was a masterstroke of personal patronage — an ostensibly munificent gesture effectively uniting Iraq’s once-rejected past in an apparently harmonious historical continuum with its present leader and his future accomplishments. More ephemeral visual propaganda, meanwhile, such as the plywood portrait of the President atop the ancient Babylonian gate of Ishtar, was similar in intent; if to Western eyes it is sometimes hilarious in effect, its message and potential is certain and clear.

Throughout such programmes he has enjoyed not only the collusion of his own artists, architects and citizens at large — thereby raising questions of collective national responsibility which Samir al-Khalil admits to finding personally uncomfortable — but also of certain key Western agencies. These range from the sponsors and consultants who assisted his architectural schemes (Mitsubishi and Ove Arup, for instance) to the good craftsmen of Basingstoke who helped to perfect the Iraqi Superwrist. And, not least, to these participatory parties must be added the observers, critics and unwitting publicists of the new wonders of Baghdad. For not just through waging war against him, and giving him some of the art and arms to fight back, do we play our part in nurturing Saddam Hussein’s all but assured historical status as a great Islamic popular hero.

• Originally appeared in The Art Newspaper with the headline "The art of being Saddam Hussein"